The third known visitor from interstellar space, comet 3I/ATLAS, is putting on a show that plays out in high‑energy light instead of visible fireworks. As it barrels through the inner solar system, the object is colliding head‑on with the solar wind, generating a sprawling X‑ray halo that exposes both the violence of that encounter and the delicate chemistry of an alien comet. For astronomers, this brutal interaction is turning 3I/ATLAS into a natural laboratory for watching the solar wind carve into pristine material from another star system.

Rather than a compact point of light, 3I/ATLAS appears in X‑rays as a diffuse, weapon‑shaped glow that stretches hundreds of thousands of kilometers into space. That glow is not just a curiosity. It is the first confirmed detection of X‑rays from an interstellar comet, and it is already challenging assumptions about how these rare visitors respond to the Sun’s radiation and magnetic storms.

The first interstellar comet in X-rays

When astronomers realized that 3I/ATLAS was not bound to the Sun, they quickly recognized an opportunity to probe material that formed around another star. Earlier interstellar objects, including the cigar‑shaped 1I/ʻOumuamua and the icy 2I/Borisov, were tracked in visible and infrared light, but neither yielded a clear high‑energy signature. With 3I/ATLAS, that changed as observatories picked up unusual X‑rays that marked the first confirmed detection of this kind of emission from an interstellar object, a result highlighted in detailed analysis. That milestone instantly elevated the comet from a curiosity to a benchmark for testing theories of how neutral gas and dust behave when slammed by charged particles from the Sun.

Optical and ultraviolet images from major facilities, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, show 3I/ATLAS as a classic dusty comet with a bright head and a sweeping tail. Those views confirm that the object is shedding gas and dust vigorously after its close pass by the Sun, which makes it an ideal target for high‑energy instruments that need a dense cloud of material to light up in X‑rays. The same outgassing that powers the visible tail is feeding the collision zone where the solar wind rams into the comet’s expanding atmosphere, a region that high‑resolution images from Interstellar observations now map in unprecedented detail.

XMM-Newton’s brutal portrait of the solar wind clash

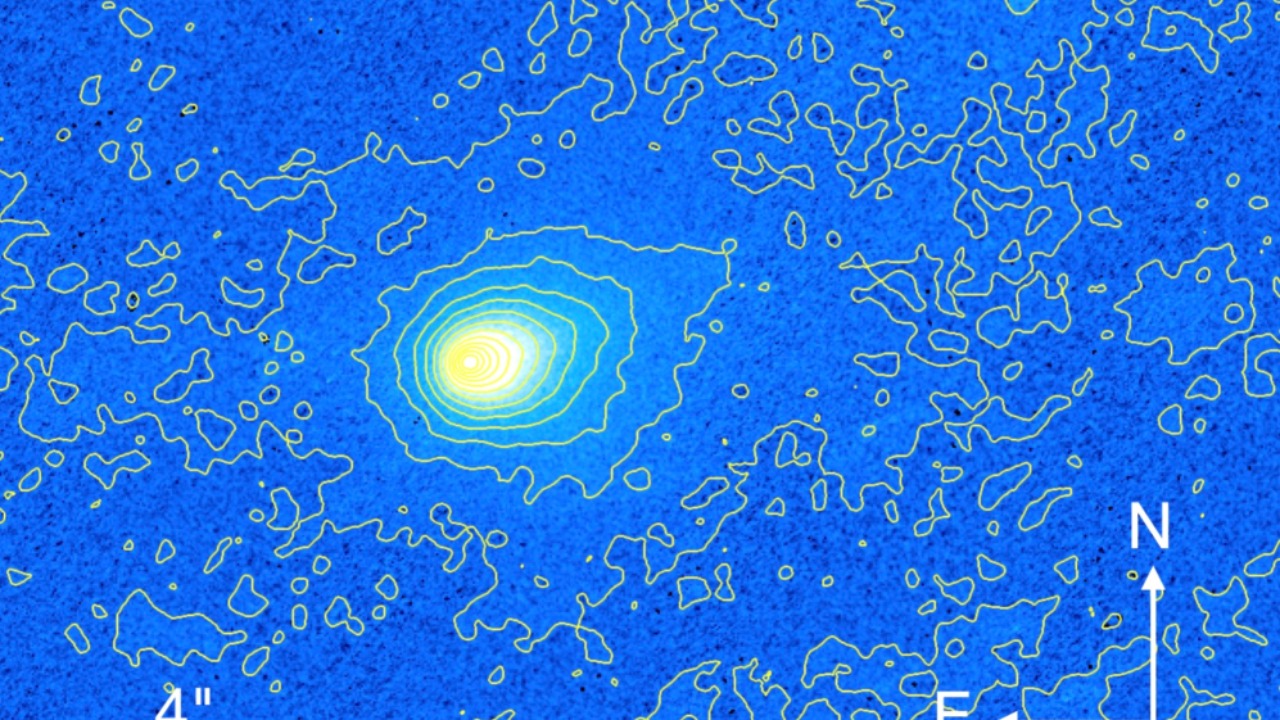

The most striking view of this clash so far comes from ESA’s XMM‑Newton observatory, which captured a dedicated X‑ray image of 3I/ATLAS as it plowed through the solar wind. Astronomers using ESA’s XMM‑Newton report that the comet appears as a red‑tinted patch of emission set against a blue background of relatively empty space, a color scheme that encodes the intensity of X‑ray photons. That contrast makes the comet’s high‑energy halo stand out as a distinct structure, not a statistical fluke, and confirms that the emission is genuinely associated with the interstellar visitor rather than with unrelated background sources.

Follow‑up analysis of the XMM‑Newton data indicates that the X‑ray glow is both extended and faint, consistent with a cloud of charge‑exchange emission rather than a compact point source. In this process, highly charged ions in the solar wind steal electrons from neutral atoms in the comet’s coma, then emit X‑rays as they relax to lower energy states. The resulting halo traces where the solar wind is being decelerated and heated, effectively sketching the shape of the bow shock that forms as the flow slams into the comet. A complementary report notes that the image reveals blue areas marking empty space with very few X‑rays, while red highlights the comet’s X‑ray emission, a pattern that researchers are now using to infer more about the comet’s composition and the structure of the surrounding space.

XRISM’s wide-field view of a 400,000-kilometer halo

While XMM‑Newton provided a sharp close‑up, the new XRISM mission delivered the wide‑angle context that shows just how far the solar wind–comet battle extends. The spacecraft’s soft X‑ray telescope, Xtend, has a field of view of roughly 1.2 m on the sky, wide enough to capture the entire X‑ray envelope around 3I/ATLAS in a single frame. Mission teams scheduled a long stare at the comet, taking advantage of its highly active state to accumulate an effective exposure of 17 hours and build up a statistically robust picture of the emission. Against this backdrop, the comet emerged as an ideal target for X‑ray observation, with a bright enough coma to stand out clearly from the diffuse cosmic background in the XRISM data Figure.

The primary analysis of those XRISM observations is consistent with a faint X‑ray glow spanning 400,000 kilometers, or 250,000 Miles, downwind from the comet’s nucleus. That scale, roughly the distance from Earth to the Moon, underscores how far the solar wind’s influence reaches once it encounters a dense cloud of neutral gas. One report describes the feature as a glowing streak 400,000 k long, a “Ray Glow Stretching” 250,000 Miles Through Space that effectively turns the comet into a gigantic fluorescent tube aligned with the solar wind. For researchers, that geometry provides a rare chance to map how the wind’s density and speed vary along the flow, using the comet as a passive probe of the heliosphere.

What the X-rays reveal about alien ices and the solar wind

Beyond the spectacle, the X‑ray spectrum from 3I/ATLAS is a diagnostic tool for both the comet’s chemistry and the solar wind’s composition. As the charge‑exchange process unfolds, different ions and atoms produce distinct line features, allowing scientists to infer which gases dominate the coma and which ions are streaming out from the Sun. Earlier observations with instruments such as the James Webb Telescope and other facilities had already spotted abundant water vapor, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide around the comet, and the new X‑ray data now tie those molecules to specific regions where the solar wind is stripping and exciting them While NASA. That combination of infrared and X‑ray diagnostics is particularly powerful, because it lets researchers cross‑check abundance estimates and test whether interstellar comets carry the same volatile mix as typical solar system comets.

In visible light, 3I/ATLAS has already shown a dramatic color shift from red to green as different gases dominate its coma at varying distances from the Sun. That change is driven by molecules such as diatomic carbon and cyanogen, which fluoresce in green when exposed to solar ultraviolet radiation, and by dust that scatters sunlight more efficiently at redder wavelengths. The same collision that powers those color changes also creates X‑rays, revealing gases that are otherwise hard to detect and making the comet “excitingly different in particular ways” compared with its predecessors, as one analysis of the red‑to‑green transition notes Dec. By tying the X‑ray brightness to specific color zones in the coma, scientists can now test how the solar wind interacts with each gas species and whether interstellar ices respond differently from those that formed around the Sun.

A survivor of a violent solar blast, heading back to the dark

The X‑ray fireworks around 3I/ATLAS are all the more remarkable because the comet has already endured a punishing encounter with the Sun. Earlier in its passage through the inner solar system, the Interstellar Comet survived a violent energy blast from the Sun that some commentators seized on to spark Alien technology theories, even as mainstream astronomy emphasized natural explanations for the object’s resilience and the observed loss of material from its surface Solar Blast Tests. That episode likely stripped away some of the outer layers of volatile ices, exposing fresher material that is now feeding the intense outgassing and X‑ray emission seen by XMM‑Newton and XRISM. In effect, the Sun’s outburst may have sandblasted the comet into a more revealing state, peeling back weathered crust to uncover pristine interstellar chemistry.

More from Morning Overview