For more than a century, a single metal cylinder in a Paris vault quietly defined what a kilogram was. After 130 years, scientists deliberately killed that object’s authority and rebuilt the standard around the unchanging rules of quantum physics. The mass you see on a kitchen scale has not shifted, but the way the world defines that mass has been fundamentally rewritten.

The change was part of a broader overhaul of the International System of Units, replacing fragile artifacts with constants of nature. By tying the kilogram to a fundamental constant instead of a lump of metal, metrologists aimed to future‑proof every precise weighing experiment, from drug doses to satellite components, against the slow drift of time and matter.

From a platinum cylinder to a global problem

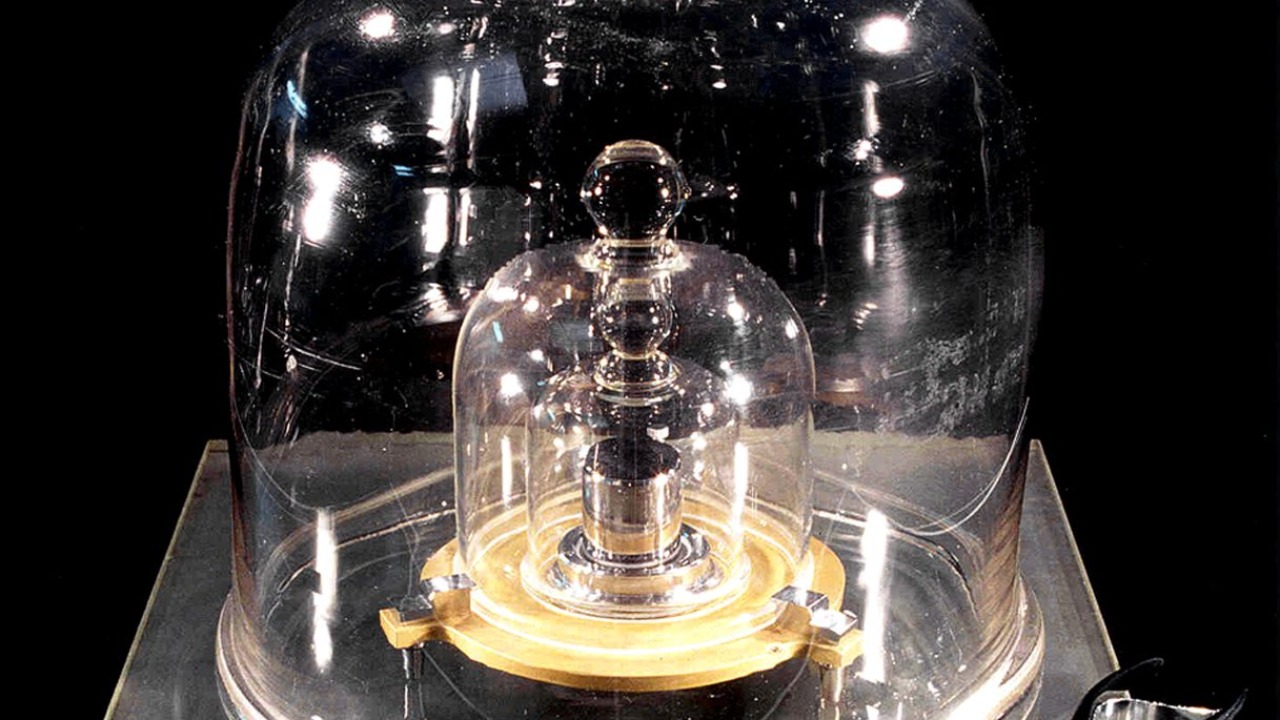

The old kilogram, formally the International Prototype of the Kilogram, was a polished cylinder of platinum and iridium stored under lock and key near Paris. Copies of this prototype, including national standards held by laboratories around the world, were periodically compared back to the original to keep everyone’s scales aligned. As the mass of these national prototypes slowly changed, careful comparisons showed that the reference cylinder itself could not be perfectly stable, even though it was treated as the definition of the unit, a tension that sat at the heart of the system for decades.

Metrologists documented that, Beyond the expected wear and tear that check standards experience, the mass of even carefully stored national prototypes could drift relative to the original, likely because of surface contamination and the solvents used to clean them. Because the International Prototype of the Kilogram, often shortened to IPK, was itself the definition, it could not officially gain or lose weight, yet comparisons showed that replicas diverged by tens of micrograms over time, a problem that one account captured by noting that, Instead of the heavens shifting, the metal itself was changing.

Why scientists decided the artifact had to die

Physicists and engineers had long been uneasy with a unit of mass that depended on a single, aging object. As precision experiments pushed into regimes where a few parts in a hundred million mattered, the inevitable instability of a physical artifact became unacceptable. One analysis noted that Physicists and engineers were frustrated by the imprecision of a standard based on a solitary cylinder, because any subtle change in that object rippled through every calibrated mass on Earth.

As the kilogram was defined as the mass of Le Grand K, the nickname for the prototype, every few decades the replica kilograms were brought back to Paris for comparison, and the resulting data showed that the system had been drifting for many years. All prototype‑based definitions share this flaw, as one atomic‑physics perspective later emphasized, because any material object can lose atoms, gain contaminants, or respond to cleaning, which is why All prototype‑based standards eventually become unreliable at the highest levels of precision.

The quantum leap: fixing the kilogram to Planck’s constant

To escape the limitations of metal, metrologists decided to anchor the kilogram to a constant of nature that does not change anywhere in the universe. At a meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures, often shortened to the General Conference on Weights and Measures or CGP in some accounts, delegates agreed on a sweeping General Conference decision to redefine several base units in terms of fixed numerical values of fundamental constants. For the kilogram, that meant tying mass to the Planck constant, a number that links the energy of a photon to its frequency in quantum theory.

With the vote on a Friday in Nov, scientists from around the world chose to affix the kilogram to the Planck constant, a fundamental quantity that does not age, corrode, or drift. The aim of that conference, held under the international metrology framework, was to switch the definition to something that can never change, as one account of the Nov decision put it, and to do so required years of painstaking measurement work to determine Planck’s constant with extraordinary accuracy.

How laboratories now realize a kilogram

Defining the kilogram through Planck’s constant is only half the story; laboratories still need a way to realize that definition in practice. The key tool is a highly sophisticated device often called a Kibble balance, which compares mechanical power to electrical power using quantum electrical standards. With the international metrology community providing all the required measurements for updating the SI, one national institute described this as a Massive Change in how mass standards are handled in air, because the balance lets scientists derive mass from electrical quantities that are themselves tied to constants.

In parallel, other experiments use atomic physics to connect mass to frequency, exploiting the fact that atoms and molecules have characteristic energy levels that can be measured with exquisite precision. From an atomic‑physics perspective, the new definition of the kilogram fits into a broader move to base all units on invariants of nature, a shift that was codified when all seven SI base units were redefined in terms of physical constants in a set of New definitions. The 2019 revision of the SI formalized this framework, fixing exact numerical values for constants like Planck’s constant and the speed of light so that units are derived from them, a structure summarized in the 2019 revision documentation.

What changed for the rest of us

For everyday users, the most important fact is that the size of the kilogram did not jump when the definition changed. One explanation stressed that the kilogram was redefined in order to create a precise, unchanging standard for its value, not to alter how heavy 1 kilogram feels in the supermarket, and that 1 kilogram remains equivalent to about 2.2 pounds, as Henson and colleagues explained. A popular explanation framed it in simple terms: Previously the kilogram was based on an arbitrary piece of metal in France, and now it is based on a definition that derives that mass from constants, so your bathroom scale still reads the same number even though the underlying theory has changed.

The impact is felt most strongly in high‑precision industries and research labs, where even tiny uncertainties can matter. Different countries have their own national standards laboratories, and the new approach ensures that their mass measurements will remain reliable far into the future, as one overview of the change noted when explaining how Different countries rely on consistent mass measurements. On World Metrology Day, when the world celebrates the weights and measures established under the international system of units, the introduction of the new kilogram was highlighted in a video that walked through why World Metrology Day had become a milestone for mass, marking the moment when a 19th‑century artifact finally gave way to a 21st‑century constant‑based standard.

More from Morning Overview