Among animals, few life cycles are as dramatic as that of the octopus. After a single reproductive event, many females enter a rapid decline that ends with them literally tearing at their own bodies, starving and wasting away as their eggs approach hatching. Biologists now argue that this is not a gruesome accident of nature but a tightly scripted program that trades the mother’s survival for the next generation’s success.

To understand why octopuses rip themselves apart after mating, I have to follow the trail from behavior to biochemistry, from the den where a mother guards her eggs to the optic gland in her head that quietly rewires her body. The picture that emerges is of an animal whose death is as biologically deliberate as its birth.

The death spiral: what octopus mothers actually do

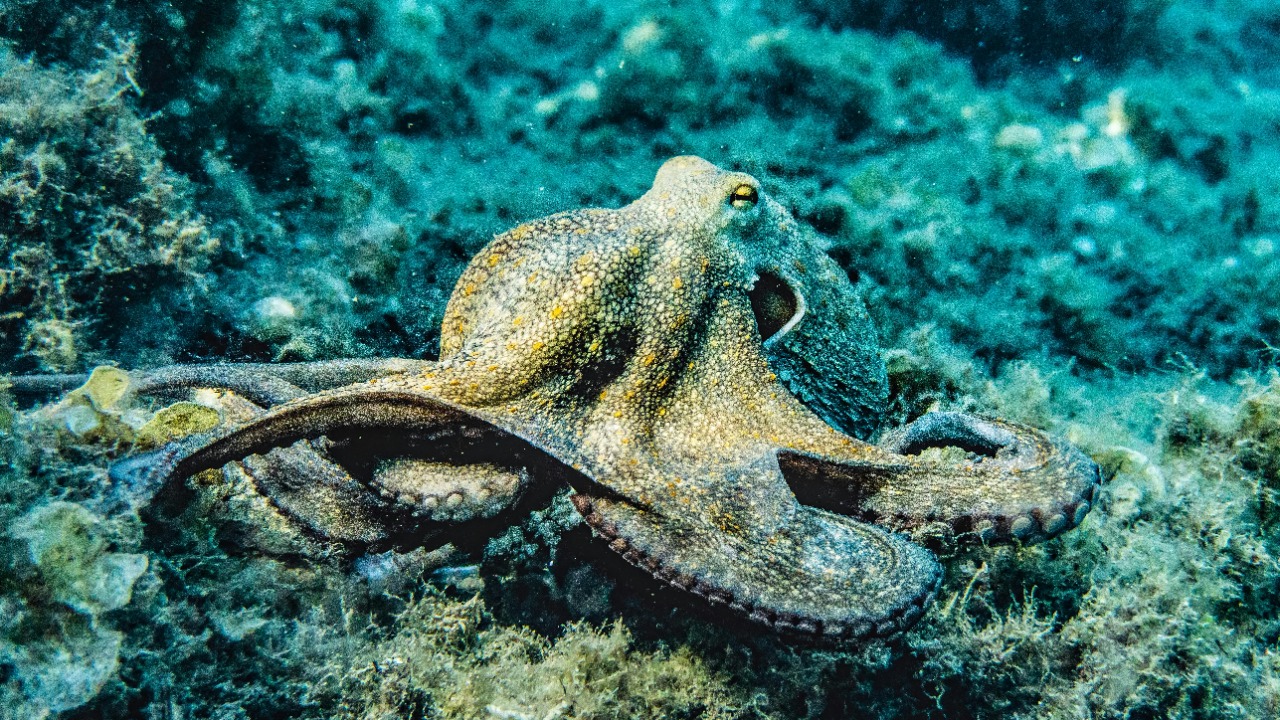

For most female octopuses, mating is the beginning of the end. After laying thousands of eggs, a mother settles into a den and devotes herself to brooding, cleaning and aerating the clutch while refusing food and ignoring everything else. As the embryos near hatching, her decline accelerates: she stops hunting, her skin pales, and she begins to engage in what looks like self-harm, slamming her body against rocks, twisting her arms and sometimes tearing at her own flesh, a pattern documented in detailed behavioral observations and in video explainers on octopus moms.

Reports describe how some of these mothers go further, biting off the tips of their arms and even consuming pieces of themselves while their eggs develop. In coverage of this phenomenon, Octopuses are described as being effectively “programmed to die,” with Science reporting that She, the brooding female, wastes away so that Many hatchlings can emerge into a world without competition from their own parent. The spectacle is so extreme that it has spilled into popular culture, with a Comments Section trading dark jokes between Fry, Zoidberg, the word Yes and the resigned Hmm about choosing between a horrible death and a life without sex.

The optic gland switch that turns on self-destruction

The key to this self-destruction sits in the octopus brain, in a structure called the optic gland that functions a bit like the mammalian pituitary. Earlier work showed that if researchers surgically removed this gland from a brooding female, she would abandon her eggs, start feeding again and live for months longer, which hinted that the gland was the control center for the death spiral. More recent analysis has gone further, tying the onset of self-mutilation to a surge of steroid production in this gland once the female has mated and laid eggs, a pattern that has been highlighted in offbeat coverage of hormones used in bile acids.

One report explains that When the eggs are laid, the optic gland begins to overproduce several steroid compounds, including precursors of bile acids, which in turn drive the octopus into a cascade of starvation, disorientation and self-injury. Researchers have linked this to a broader pattern of chemical changes in the gland, arguing that the same organ that once coordinated growth and reproduction now actively orchestrates decline, a view echoed in local coverage that describes how chemical changes in the optic gland after egg laying push the mother toward cannibalistic behavior and early death.

Cholesterol, steroids and the biochemistry of a death program

To move beyond anatomy and into chemistry, scientists have turned to tools like mass spectrometry to see exactly what the optic gland is producing before and after mating. One study, led by a team that dissected glands and optic lobes from both mated and unmated females, found that the post-mating glands were flooded with unusual steroids, including compounds related to cholesterol metabolism and bile acid synthesis. As Wang and her colleagues reported, these shifts were so dramatic that they suggested a direct biochemical route from reproduction to self-destruction, a link that has been described in detail in coverage of how Wang and her team linked specific steroids to the animals’ early demise.

Another line of research has focused on cholesterol itself, a molecule that is essential for cell membranes and hormone production but can be toxic when mismanaged. A study from Chicago traced the “death spiral” back to changes in cholesterol production and breakdown in the optic gland, arguing that the same pathways that keep the animal healthy before reproduction are repurposed to shut it down afterward. The authors noted that this offers a rare window into how steroid signaling can be rewired across the life cycle in both soft-bodied cephalopods and vertebrates alike, a point underscored in a university summary that described how changes in cholesterol production appear to be central to the bizarre maternal behavior.

Why evolution favors a mother’s gruesome end

From an evolutionary perspective, a death program this extreme only makes sense if it boosts reproductive success. Octopus mothers invest heavily in a single brood, laying eggs once and then pouring all their remaining energy into guarding and tending them. By the time the embryos are ready to hatch, the mother is already weakened, and her continued presence could turn her into a predator on her own offspring or a competitor for the same prey. One analysis of this trade-off suggested that the self-destruction may help “protect the younger octopuses” by removing a large, hungry adult from the ecosystem, a view attributed to Yan Wang, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, who told Yan Wang that this might be a way to protect the younger octopuses from the older generation.

There is also the question of why such a sophisticated, large-brained animal would be locked into a single reproductive event instead of living to breed again. Coverage of the latest work has pointed out that larger-brained animals, like octopuses, tend to live longer, which makes their programmed death particularly striking. A detailed report on this puzzle notes that a new Study identified several distinct chemical pathways in the optic gland that could account for the animal’s self-destruction, and that this pattern may reflect a deep evolutionary compromise between neural complexity and a life history built around one massive reproductive effort, a tension highlighted in a summary that cites New Scie while explaining how several pathways converge on the animal’s self-destruction.

What captivity, social life and human reactions reveal

Captive octopuses offer a stark view of how rigid this life cycle can be. Aquarists report that even without a mate, females will eventually lay unfertilized eggs and slide into senescence, ignoring food and fixating on a clutch that will never hatch. One widely shared post about a giant Pacific octopus named Ghost described how she laid eggs and entered the final stage of her life cycle, with staff explaining that Octopii lay eggs whether they have a mate or not and that once they do, they are effectively “evolutionarily dead,” a phrase that captured how little room there is to interrupt the process, as detailed in the Aquarium of the Pacific’s note that Octopii in human care still follow the same script.

Public fascination with this process has grown as more footage and explanations circulate. One viral video described how Octopus mothers slam themselves against rocks and chew on their own arms, tying the behavior to the steroid storm triggered by the optic gland, a narrative echoed in a lifestyle piece that framed the optic gland’s steroid output as the spark that leads to the self-destruction of the Octopus mother. Social media explainers have emphasized that many animal species die after they reproduce, But in octopus mothers, this decline is particularly alarming because it involves active self-mutilation rather than a quiet fading, a contrast that has been highlighted in a video that stresses how But in octopus mothers, the decline is especially dramatic.

More from Morning Overview