The United States is no longer content with brief lunar visits powered by batteries and solar panels. NASA is now betting on nuclear fission to turn the Moon from a destination into a permanently powered outpost, with a reactor-sized “power grab” that could reshape who sets the rules in deep space. The agency’s plan to plant a compact nuclear power station on the lunar surface by around 2030 is as much about geopolitics and law as it is about engineering.

At stake is the ability to run habitats, mines, and factories in places where sunlight is scarce and survival margins are thin. By moving first on nuclear power, the United States is trying to lock in the infrastructure that will support Artemis crews, robotic explorers, and eventually commercial operators, while signaling to rivals that it intends to lead the next phase of the space race.

From solar panels to fission: why NASA is changing the power game

For decades, space missions have relied on solar arrays and small radioisotope generators, but those options break down when you want a permanent base in a place that spends long stretches in darkness. NASA’s own description of fission systems stresses that, unlike power on Earth, electricity on the Moon and Mars is not just a matter of plugging into a grid, it has to be generated locally in harsh, isolated conditions. Solar power is especially fragile near the lunar poles, where Artemis is headed, because the Sun skims the horizon and dust can easily blanket panels.

That is why the agency and the Department of Energy are now treating “Fission Surface Power” as a core technology rather than a science experiment. In official material on Fission Surface Power, NASA frames nuclear reactors as a way to provide steady electricity regardless of local weather, dust storms, or the two-week lunar night that would shut down most solar-dependent systems. The shift is not about abandoning solar, but about adding a reliable backbone that can keep life support, communications, and industry running when sunlight disappears.

The 100-kilowatt target and how the reactor would actually work

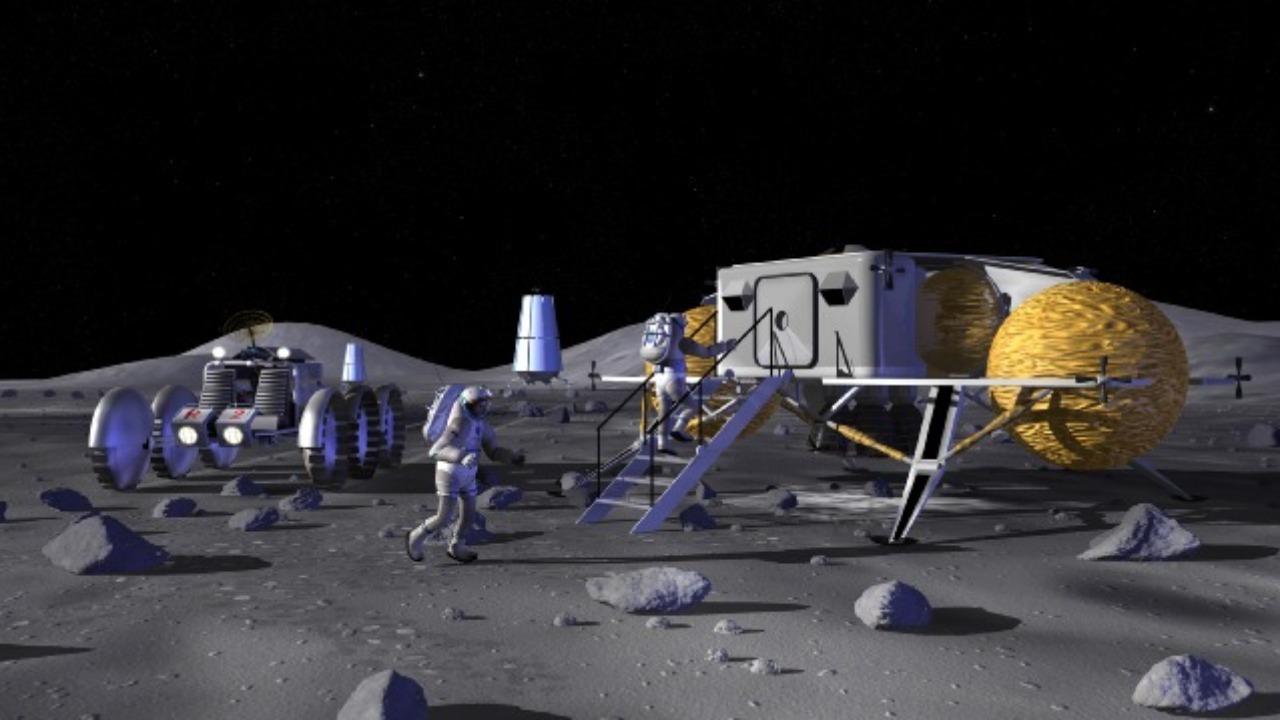

NASA is not talking about a giant terrestrial-style plant, but a compact unit sized for a frontier town. The agency has set a goal of deploying a 100-kilowatt fission reactor on the Moon, enough to power a small cluster of habitats, rovers, and processing equipment. Reporting on NASA’s lunar plans notes that this level of output would be transformative for exploration, akin to moving a settlement from candlelight to a functioning electric grid, because it would finally allow continuous operations instead of rationed power.

To get there, NASA and DOE are developing modular “Fission Surface Power Systems” that can be launched on a single rocket and assembled with minimal astronaut intervention. A DOE explainer on Fission Surface Power describes a setup where a small uranium core, shielded and buried for safety, drives turbines or other conversion units that feed power lines to habitats and equipment. The same overview notes that the demonstration system is being designed to survive extreme temperatures and operate autonomously, which is essential on a world where maintenance crews may be hundreds of thousands of kilometers away.

Artemis, industry partners, and the 2030 deadline

The nuclear push is tightly bound to the Artemis program, which aims to put crews near the lunar south pole and keep them there for long stretches. NASA has said it wants a surface reactor in place by around 2030 to support Artemis and Mars ambitions, including power for habitats, in situ resource utilization plants, and rovers that can travel far from base. Agency material emphasizes that the same technology could later be adapted for Martian outposts, turning the Moon into a proving ground for deeper exploration.

To hit that schedule, NASA has turned to private companies and the Department of Energy in a more formal way. A recent agreement between NASA and DOE is framed as a step toward closer collaboration on nuclear energy and space exploration, pooling reactor expertise with mission design. At the same time, NASA has invited companies to weigh in on requirements through its Fission Surface Power effort, which builds on 60 years of experience and is explicitly linked to strengthening national security in space.

Why nuclear beats sunlight at the lunar poles

At first glance, covering the Moon with solar panels might seem simpler and safer than shipping a reactor. In practice, the physics of the lunar environment tilt the balance toward fission. Analyses of why nuclear is favored point out that sunlight is intermittent, dust can degrade panels, and energy storage for the two-week night would require enormous batteries or fuel cells. By contrast, a buried reactor can deliver baseload power day and night, independent of local conditions.

Companies working on advanced reactors make a similar case. One nuclear developer describes how sustained Moonbases will need a reliable source of baseload power that does not depend on constant sunlight, and that can run for years with little refueling. The same firm notes that a compact fission unit can be designed as a sealed, low maintenance source, which is critical when every kilogram of spare parts has to be launched from Earth.

Safety, law, and the politics of a “power grab”

Putting a reactor on the Moon is not just an engineering problem, it is a legal and diplomatic one. An Analysis of why NASA is planning to build a nuclear reactor on the Moon notes that a lunar nuclear reactor may raise questions about access and power, in the political sense as much as the electrical one. The Outer Space Treaty bans national appropriation of celestial bodies, but it does not forbid infrastructure, which means whoever controls the power plant could wield outsized influence over who gets to plug in.

Legal scholars stress that building infrastructure is not the same as staking a territorial claim, but they also warn that control over energy, landing pads, and communications could effectively decide who can operate on the surface. A separate commentary on how While a nuclear reactor on the Moon might once have seemed distant, the growing push by states to secure a sustainable habitat in Space is increasing, underlines how quickly norms are being tested. In that context, NASA’s nuclear move looks like a bid to define standards before others do.

More from Morning Overview