The United States is no longer talking abstractly about nuclear power in space. It is now working to place a working fission reactor on the lunar surface by around 2030, turning a long‑discussed concept into a concrete deadline. The plan is framed as essential to sustaining human activity on the Moon for weeks at a time and to extending that capability deeper into the solar system.

NASA officials describe nuclear power as the backbone of a future lunar economy, arguing that solar panels alone cannot keep bases running through the two‑week polar night. The agency’s public messaging has shifted from cautious exploration of options to a clear commitment to build and deploy a compact reactor that can survive launch, landing and years of operation in one of the harshest environments humans have ever tried to inhabit.

The 2030 deadline and a new nuclear space doctrine

NASA has now tied its lunar ambitions to a specific clock, stating that the United States intends to have a nuclear reactor operating on the Moon by about 2030. In public briefings, officials have framed this as a national objective, with NASA and the Department of Energy both committing to deploy fission systems that can be launched within the next few years. The US is treating this as a race to secure reliable power on the lunar surface before other nations can lock in strategic footholds.

That urgency is reflected in the way senior leaders talk about the project. NASA’s messaging, echoed by Jan statements that “Achieving this future requires harnessing nuclear power,” makes clear that the agency sees fission as the only realistic way to keep habitats, laboratories and communication systems running through long lunar nights, when solar arrays produce nothing and batteries alone would be prohibitively heavy. The US is effectively declaring that if it wants a permanent presence on the Moon, it must become a nuclear power in space, a stance underscored by The US rhetoric around energy as the foundation of exploration.

NASA, DOE and a fast‑tracked reactor program

To turn that doctrine into hardware, NASA has deepened its partnership with the Department of Energy, effectively merging spaceflight experience with nuclear engineering expertise. In Jan, NASA and the formalized a renewed collaboration that sets out how the two agencies will share responsibilities for design, safety analysis and eventual deployment of lunar surface reactors. Under that agreement, reactors should be prepared to launch by the first quarter of the relevant fiscal year, a schedule that leaves little slack if the 2030 target is to be met.

The Department of Energy’s role is not limited to paperwork. Officials describe a program in which DOE laboratories and contractors will build and test compact fission units on Earth, while NASA focuses on integrating those systems into landers and surface infrastructure. Jan statements from The USA emphasize that NASA and the Department of Energy are teaming up to create reactors that can be mass‑produced and adapted for future missions, including potential use in cislunar space and in orbit around the Moon.

Why the Moon needs nuclear power

The case for a reactor on the Moon starts with basic physics. Lunar days and nights each last about two Earth weeks, which means any base that relies solely on solar power must either shut down for half the time or carry enormous energy storage systems. NASA has been explicit that it aims to land a nuclear reactor on the Moon by around 2030 to supply steady power for lunar bases, especially during the long, cold nights at high latitudes, a goal highlighted in Jan briefings about supporting Moon research and future missions.

Fission systems also offer independence from local terrain and dust conditions that can degrade solar panels and block sunlight. NASA’s technical descriptions point to compact reactors that can deliver continuous power regardless of weather conditions, unlike solar panels that depend on direct illumination and clear lines of sight. One Jan report notes that NASA plans to create a nuclear reactor on the Moon by 2030 and intends to establish a nuclear power plant that can operate through extreme temperature swings and regolith storms, with Details stressing that such systems are not vulnerable to changing weather conditions, unlike solar panels.

Geopolitics, Trump’s space policy and fears of “keep‑out zones”

The technical rationale sits atop a very political foundation. Under President Trump’s national space policy, nuclear energy has been framed as a strategic asset that can help the United States secure leadership in cislunar space. Former Acting Administrator Sean Duffy has argued that “Under President Trump’s national space” direction, nuclear power is central to long‑term exploration, a view reflected in Jan coverage of Former Acting Administrator and his push to expedite the lunar reactor timeline.

Mr Duffy has also been unusually blunt about the geopolitical stakes. He has warned that China and Russia could try to “declare a keep‑out zone” on parts of the Moon if they establish their own infrastructure first, a scenario he cited while arguing that the United States must move quickly to secure access to key polar regions. His comments about China and Russia were framed as a response to growing competition for lunar resources, including water ice that could be turned into rocket fuel, and they underline how energy projects are now intertwined with broader questions of space dominance.

From lunar bases to Mars and beyond

NASA officials are clear that the Moon is only the first step. The same fission surface power systems that keep a polar base running could eventually be adapted for missions to Mars, where sunlight is weaker and dust storms can last for weeks. A Jan analysis of a DOE‑NASA memorandum notes that the agreement promotes the lunar reactor project with a view to future missions to Mars, describing how the United States is consolidating energy as the axis of space dominance and how United States planners see nuclear power as the backbone of that strategy.

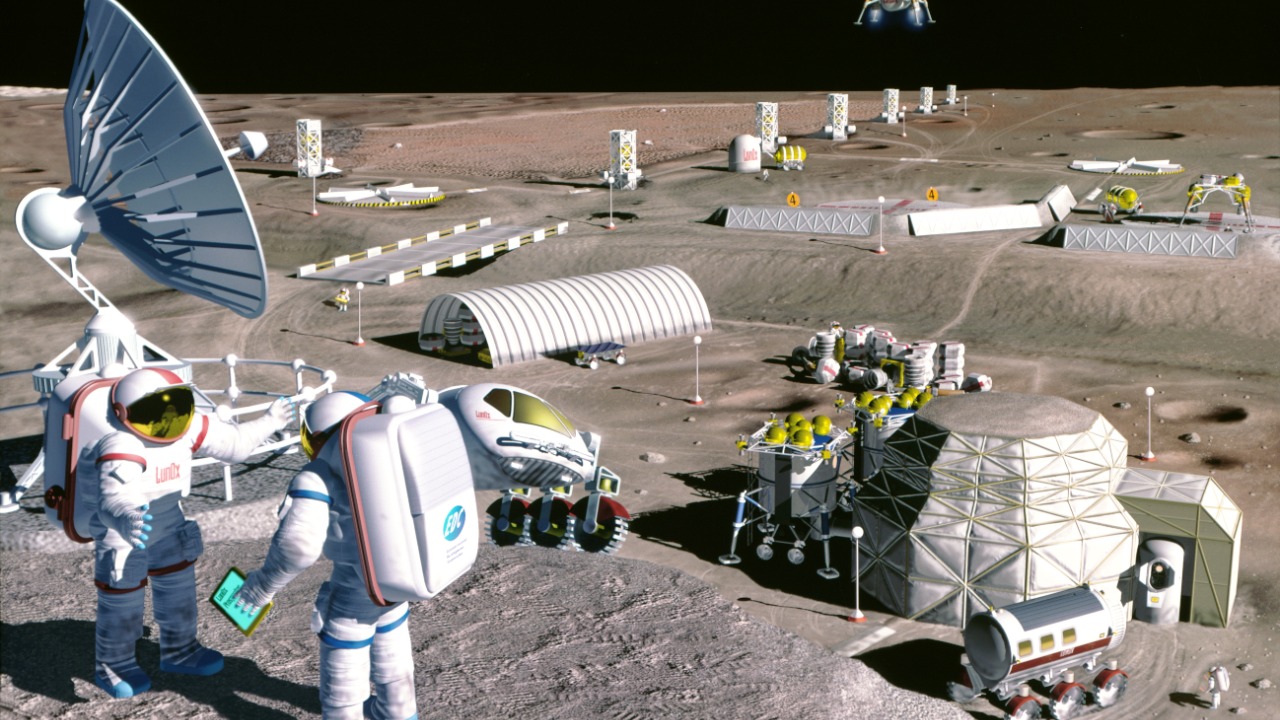

Inside NASA, the reactor effort is now treated as part of a broader portfolio of surface systems that will support both robotic and crewed missions. Jan coverage of the agency’s commitments describes how NASA “Commits to Plan to Build Nuclear Reactor” hardware that can be scaled and replicated, with a 2024 concept image of its fission surface power system illustrating the kind of modular units that could be shipped to multiple sites. That same reporting notes that NASA is treating the lunar reactor as a template for future off‑world grids, not a one‑off experiment.

More from Morning Overview