The United States is quietly fielding a new class of kamikaze-style drones that look strikingly similar to Iran’s Shahed family, betting that copying an adversary’s cheap, expendable weapon is the fastest way to blunt its impact. The move reflects a hard lesson from Ukraine and the Middle East: low-cost loitering munitions can overwhelm even sophisticated defenses if they arrive in large enough numbers. I see Washington’s emerging “knockoff” strategy as less a technological leap than a political signal to Tehran that the same playbook can be used against it.

From Iranian export to American template

Iran’s Shahed series has become one of the most consequential weapons of the past few years, not because it is advanced, but because it is simple, cheap and fielded at scale. In Ukraine, Russia has used the Shahed, including the Shahed‑136, in relentless waves to probe and exhaust air defenses, forcing Kyiv and its partners to spend expensive interceptor missiles on relatively crude flying bombs. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Russia’s persistent use of these low-cost drones is a textbook example of how quantity can erode even layered defenses by overwhelming radars, command networks and missile stocks in a prolonged campaign.

American planners have been watching that pattern closely, and they are clearly worried about seeing a similar saturation tactic in the Gulf. According to the Center for Strategic, Russia’s approach underscores how “low-cost drones” can be used to overwhelm air defense systems “with sheer numbers,” a scenario that maps neatly onto U.S. concerns about Iranian arsenals threatening bases, tankers and partner infrastructure across the region. That is the strategic backdrop for why copying the Shahed design, rather than ignoring it as a crude knockoff, has become a priority in Washington.

Reverse engineering the Shahed into FLM‑136

Instead of treating the Shahed as a curiosity, The Air Force has moved to study it in forensic detail. Earlier, The Air Force asked industry for an “exact replica” of the Shahed‑136, explicitly to test and refine defenses against the kind of low, slow, noisy threat that traditional fighter jets and high-end missiles are poorly optimized to stop. That requirement signaled a shift in mindset: to defeat a weapon like this, U.S. engineers first want to fly it, break it and understand exactly how it behaves in the air and on radar. The same logic has now been extended from test ranges to operational units.

The result is a new loitering munition that American officials and analysts describe as a near twin of Iran’s design. The US version is manufactured by SpektreWorks and known as the FLM 136, a designation that deliberately echoes the Shahed‑136 lineage while signaling that this is now an American system. By Reverse‑Engineering Shahed Drone, the United States is, as analyst Paul Iddon puts it, Giving Iran a Dose Of Its Own Medicine, mirroring Tehran’s long history of building derivatives of U.S. weapons systems and turning them back against American interests.

LUCAS squadrons and a new kamikaze doctrine

The Pentagon has not only copied the airframe, it has wrapped it in a new operational concept. The U.S. military has stood up its first operational unit armed with the Low, Cost Uncrewed Combat Attack System, or LUCAS, a kamikaze drone squadron that uses Shahed‑style munitions as its core weapon. The idea is to field large numbers of expendable aircraft that can loiter, hunt for targets and then dive in, trading metal and fuel for the survivability of pilots and high-end jets. In effect, Washington is building its own swarm-capable strike arm, optimized for the same kind of attritional, numbers-driven warfare that Iran and Russia have embraced.

Marine forces are already experimenting with how such a squadron might fight. The Marine Corps is testing LUCAS kamikaze drones that are American reverse engineered Shahed‑136 clones costing $35,000 per unit, with 1,50 in planned mass production across multiple manufacturers, figures that underscore just how aggressively the services are chasing affordability. At $35,000, these drones are cheap enough to be bought and lost in bulk, yet still precise enough to threaten radars, missile batteries and small naval vessels, a combination that could reshape how U.S. forces think about suppressing enemy defenses in the Gulf.

Deployment to the Middle East and signaling to Tehran

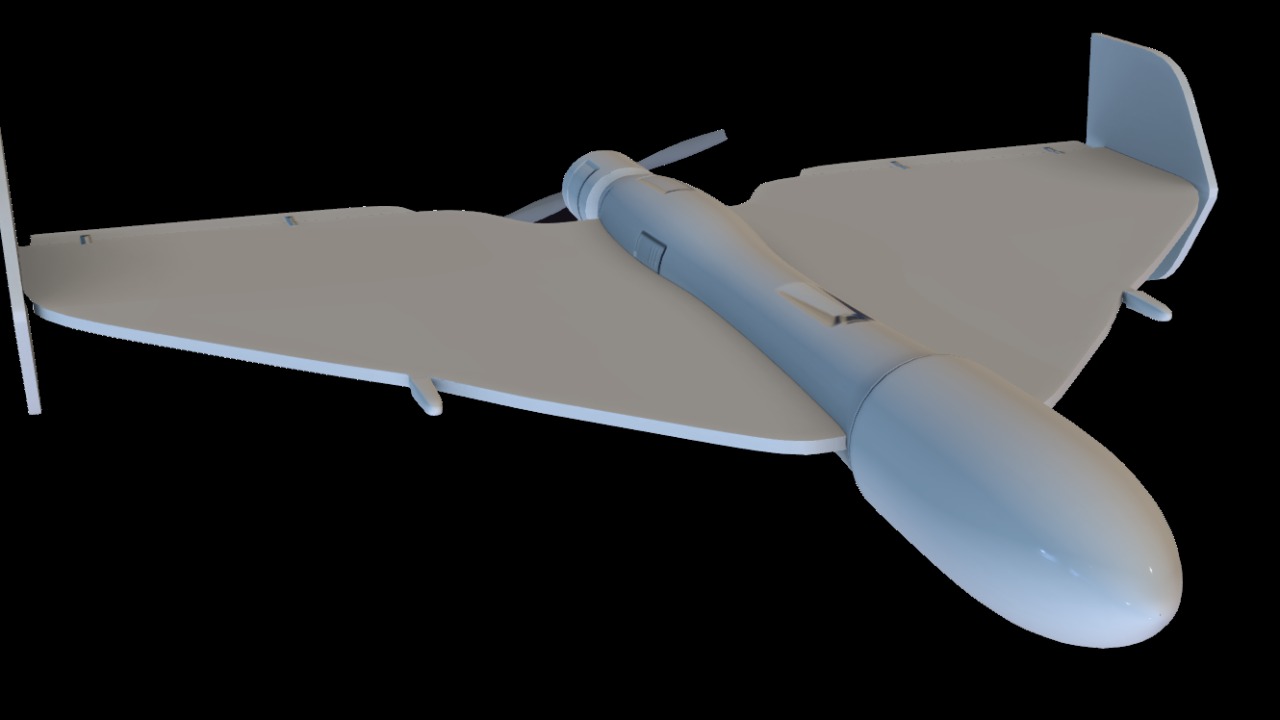

What began as a test project has already moved into the field. The U.S. military has deployed Shahed‑style clones to the region, with FLM‑136 Drones Now Deployed in the Middle East as part of a broader effort to deter Iran and reassure partners. Video and imagery circulating online show that the FLM 136 drone closely resembles the Shahed‑136, with a similar delta wing and pusher propeller layout, a visual echo that is hard to miss for Iranian planners watching from across the Gulf. For U.S. Central Command, fielding this system is about more than hardware, it is about demonstrating that American forces can respond to Iran’s preferred tools with mirror-image capabilities of their own.

Officials have framed the new squadron as a flexible asset that can be surged or repositioned as adversaries move. In one account, a Pentagon briefing described how the new unit is being integrated into regional force posture so it can respond quickly as Iranian proxies shift launch sites or as shipping threats evolve, a point highlighted in a briefing that emphasized the need to adapt as adversaries move. For Tehran, the message is clear: the same kind of low-cost, long-range kamikaze threat it has exported to partners and clients can now be turned back toward Iranian assets if escalation spirals.

Lessons from Ukraine and the next phase of drone warfare

American officials are explicit that Ukraine’s experience is shaping their thinking. In the war in Ukraine, Russia’s use of Shahed‑type drones has forced defenders to improvise with everything from anti-aircraft guns to electronic warfare, and U.S. planners are determined not to be caught flat-footed. One Pentagon overview noted that the FLM 136 drone closely resembles the Shahed‑136, with similar performance characteristics, precisely so U.S. forces can test how best to detect and shoot them down, a point underscored in a technical summary. By flying their own clones, U.S. units can refine radar settings, intercept tactics and even software updates for air defense systems before facing Iranian-built versions in combat.

There is also a political and informational dimension to this copycat strategy. America deploys copy‑cat kamikaze drones based on the Shahed design in part to show that it can absorb and repurpose adversary technology, a narrative captured in online footage that highlights how Winglore and other innovators have contributed to the broader ecosystem of low-cost unmanned systems. At the same time, the Pentagon has used public briefings, including one framed around a Video Player that could not be loaded, to stress that learning from enemy weapons is now standard practice, as noted in a public account that framed the FLM‑136 as part of a broader effort to study enemy weapons. As President Donald Trump’s administration leans into this approach, the quiet deployment of Shahed-style knockoffs signals that the next phase of drone warfare will be as much about imitation and adaptation as it is about invention.

More from Morning Overview