Lasers, heat and a notoriously tricky element are at the center of a quiet revolution in how the United States plans to power missions far beyond Mars. At Oak Ridge National Laboratory, researchers are firing precision beams at neptunium to understand exactly how it behaves as it is turned into plutonium fuel for compact nuclear power systems. Their goal is simple but ambitious: map the material so thoroughly that future deep-space reactors can be designed with confidence instead of educated guesswork.

The work is part of a broader push to secure reliable nuclear energy for spacecraft that will travel too far from the Sun for solar panels to be practical. By refining how neptunium is processed and transformed, the team is laying the groundwork for more efficient production of plutonium-238, the isotope that keeps robotic explorers warm and powered in the cold dark of deep space.

Why neptunium sits at the heart of deep-space power

For decades, the limiting factor in nuclear power for space has not been engineering talent or mission ideas, it has been fuel. Plutonium-238 is the workhorse isotope that feeds radioisotope power systems, but it does not occur in nature in useful quantities. Instead, it is bred from neptunium targets that must be fabricated, irradiated and chemically processed with extreme care. At Oak Ridge National Laboratory, that chain begins with neptunium oxide blended into aluminum, a mixture that is pressed into targets and later converted into the heat source for long-lived generators.

Earlier work at ORNL focused on automating the production of these neptunium oxide aluminum pellets to make plutonium-238, often written as 238, more reliably and at higher throughput. That automation effort turned a delicate, hands-on process into something closer to industrial manufacturing, a crucial step for any sustained program of deep-space exploration. The new laser mapping campaign builds directly on that foundation, treating neptunium not just as a feedstock but as a material whose microscopic behavior can be tuned and predicted.

Lasers, heat and a 3D map of a difficult element

The latest experiments at Oak Ridge National Laboratory use high intensity lasers and controlled heating to probe how neptunium changes as it moves through each stage of fuel production. Researchers are effectively building a three dimensional atlas of the element, tracking how its crystal structure, impurities and defects evolve under different thermal conditions. By correlating those changes with performance in reactors and radioisotope systems, they can identify which processing paths yield the most stable and predictable fuel.

In this work, the team is not simply taking snapshots of neptunium at a few temperatures. They are using lasers to induce precise thermal gradients, then reading out how the material responds in real time. That approach allows them to map subtle transitions that might otherwise be missed, such as the onset of phase changes or the formation of microscopic cracks that could compromise a fuel pellet over decades in space. The result is a data rich picture of neptunium that feeds directly into models for the creation of deep-space fuel.

From lab bench to reactors bound for the outer planets

The immediate payoff from this laser mapping is better control over how neptunium targets are fabricated and processed, but the downstream impact is on the power systems that will ride on spacecraft. Radioisotope generators and compact reactors must operate for years without maintenance, often in environments where temperatures swing wildly and radiation levels are intense. If the fuel inside those systems behaves unpredictably, the entire mission is at risk. By tightening the tolerances on neptunium based fuel, Oak Ridge National Laboratory is effectively de-risking the next generation of deep-space power units.

Researchers at Oak Ridge National frame the work in terms of what it enables: instruments on long range missions that can run continuously, landers that can survive frigid nights on distant moons and probes that can operate in the shadowed regions of icy worlds where sunlight is scarce. The more precisely they can characterize neptunium, the more confidently mission designers can size power systems, manage heat and plan for contingencies. In practical terms, that means fewer conservative design margins and more room for science payloads.

A long campaign to industrialize plutonium-238

The laser experiments are the latest chapter in a long running effort to rebuild the United States supply chain for plutonium-238. After a long pause in domestic production, ORNL took on the task of restoring and then scaling up the capability to make this critical isotope. Automating the fabrication of neptunium oxide aluminum targets was a pivotal step, reducing worker exposure and improving consistency. That automation, combined with careful process control, has allowed the lab to move from demonstration scale batches toward more routine output suitable for multiple missions.

Earlier reporting on neptunium targets highlighted how the lab integrated robotics and custom tooling to handle the oxide aluminum mixture. That same mindset is now being applied to the characterization phase, where lasers and advanced sensors replace some of the trial and error that once defined nuclear materials work. By treating plutonium-238 production as an industrial process rather than a bespoke craft, ORNL is aligning deep-space fuel with the kind of reliability standards more commonly associated with commercial power plants.

Deep-space stakes and the next wave of missions

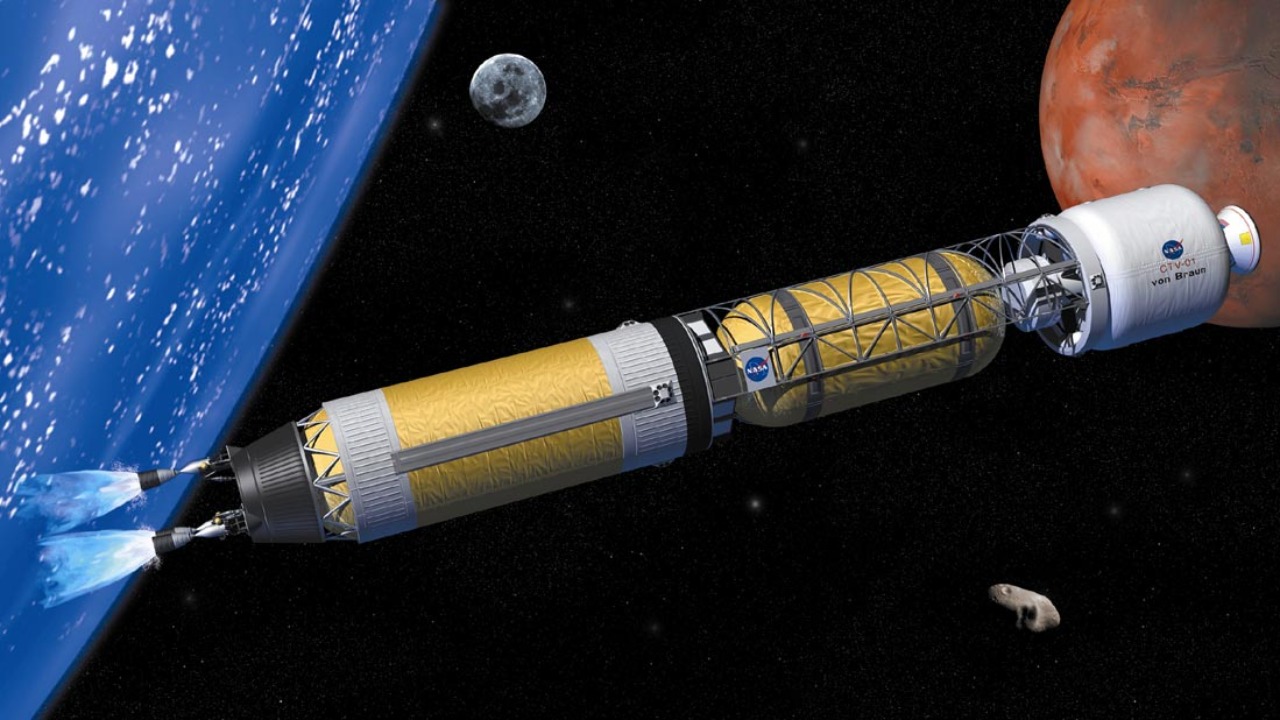

The stakes for getting this right are high. Missions to the outer planets, their moons and the Kuiper Belt will depend on nuclear power not just for electricity but for thermal management, keeping instruments and propellant lines within operating ranges. Solar arrays that work for a rover like Perseverance on Mars become impractical at Saturn or beyond. That is why the detailed mapping of neptunium, and the resulting improvements in plutonium-238 fuel, are being treated as enabling technologies rather than incremental lab curiosities.

As reports on the program note, the work is vital for deep-space exploration because it underpins the power sources that keep instruments running on long range missions. I see a direct line from the laser lab at Oak Ridge to future probes orbiting Uranus, landers on Enceladus or sample return missions from comets that spend most of their time in the dark. Each of those concepts assumes a compact, rugged power system that can be trusted for a decade or more, and that trust is being earned now, one mapped neptunium sample at a time.

More from Morning Overview