The United States is preparing to subject fusion reactor materials to a brutal new benchmark: a focused 10 megawatt heat blast that rivals the surface of the sun. At Oak Ridge National Laboratory, researchers are building a facility designed to hurl that intensity at metal and ceramic components so engineers can see what survives and what fails. The goal is simple but sweeping, to clear one of the last major technical hurdles between experimental fusion devices and power plants that can run on a commercial grid.

The new testbed will sit at the center of a broader fusion campus in East Tennessee, where federal scientists, private companies and universities are trying to turn decades of physics research into practical hardware. If it works as planned, the project could compress years of wear and tear into days of testing, giving designers the data they need to harden future reactors against the most punishing conditions inside a fusion machine.

Oak Ridge’s 10 MW heat gauntlet

The planned facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, or ORNL, is being built to expose candidate reactor materials to a heat flux of 10 megawatts per square meter, a level that pushes into the same regime as the most stressed surfaces inside a working fusion device. Engineers want to recreate the thermal and particle bombardment that components will face near the plasma edge, where superheated fuel brushes against the walls. According to project descriptions, the setup is intended to match the intense heat flux and operational stresses that future reactors will impose on divertors, first walls and other critical parts.

To reach those conditions, ORNL is pairing its existing fusion science expertise with a new industrial partner. The lab has agreed to work with Type One Energy and the University of Tennessee to create what they describe as a world class platform for validating next generation fusion technology. The collaboration is meant to ensure that the 10 MW test environment does not exist in isolation but feeds directly into the design of commercial scale machines, including the stellarator concepts that Type One Energy is pursuing.

A fusion campus rises at Bull Run

The new heat test facility is part of a larger redevelopment of the former Bull Run Fossil Plant site in East Tennessee, where energy leaders are planning a dedicated fusion campus. The site, once home to a coal fired power station, is being reimagined as a cluster of experimental halls, power infrastructure and support buildings tailored to fusion research. Local planners say that there researchers will test how materials react under intense heat in a fusion device, with core construction targeted for completion by 2027 so the campus can support early pilot projects.

One of the central ambitions for Bull Run is to shorten the feedback loop between laboratory experiments and real reactor designs. Project backers describe one of their core goals as speeding up the development of components that must withstand the roughest operational conditions, then feeding those results directly into fusion pilot plant designs. By clustering ORNL, Type One Energy and the University of Tennessee on a single campus, they hope to move from concept to tested hardware without the delays that come from shipping prototypes around the country or waiting for scarce time on foreign machines.

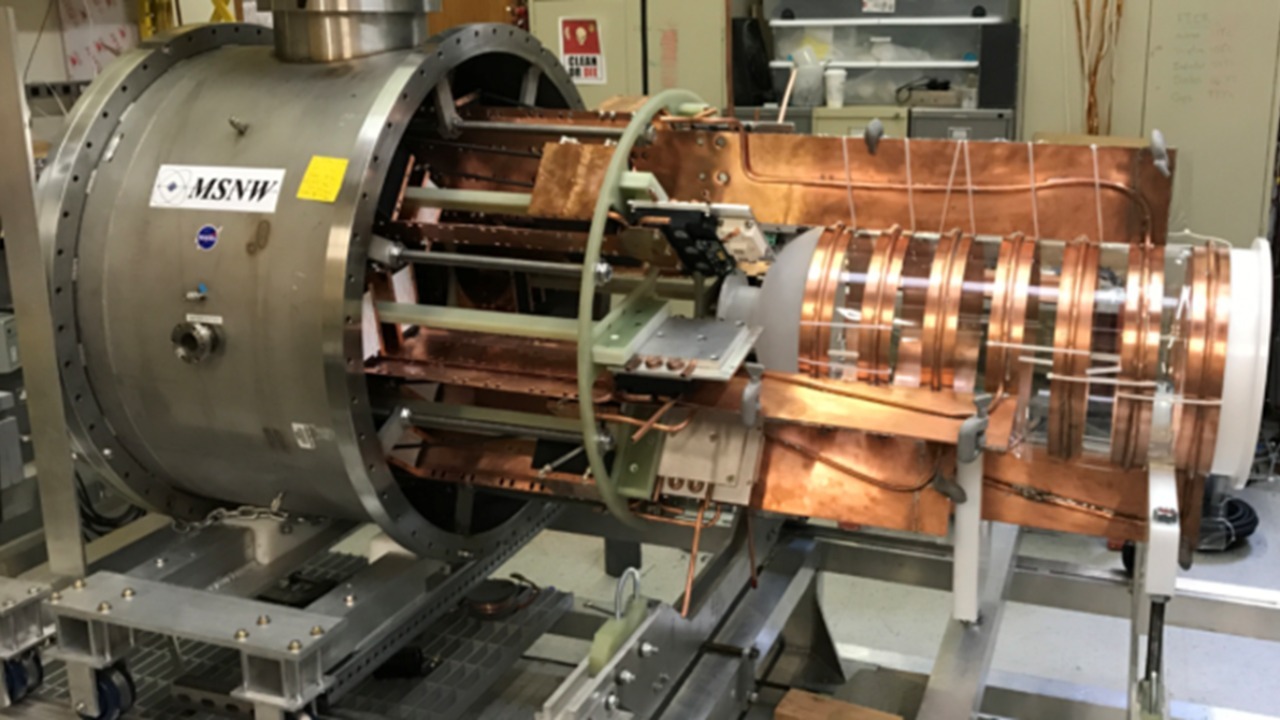

MPEX and the “heat shield” problem

The 10 MW testbed is not starting from scratch. At ORNL, the Materials Plasma Exposure Experiment, known as MPEX, has been under development for years as a dedicated platform to study how plasma erodes and alters reactor walls. Earlier program descriptions likened the challenge to building a spacecraft heat shield, with MPEX program manager Juergen Rapp explaining that developing materials for a fusion reactor is like designing protection that can survive repeated, searing reentry conditions without burning up.

Local reporting from Oak Ridge has emphasized that MPEX is expected to be operating by 2027 at ORNL, with the Material Plasma Exposure device seen as a key step toward fusion electricity that could be available by 2040. Another account notes that, at ORNL, the Materials Plasma Exposure is designed to reproduce years of fusion conditions in only two weeks, compressing the wear that a reactor wall would experience over long campaigns into a manageable experimental window. The new 10 MW facility is expected to complement that work by focusing on even more extreme heat fluxes and integrated component tests.

From national strategy to local ecosystem

Federal planners have been explicit that this kind of facility fills a gap in the national fusion roadmap. The Department of Energy has identified a critical need for a fusion facility that can test materials at temperatures hotter than the sun, including the ability to evaluate thermal performance, structural integrity and chemical inertness with blanket components that will breed tritium fuel. By anchoring that capability at ORNL, the government is betting that the lab’s long history in nuclear science and materials research can accelerate the path from experimental physics to deployable power plants.

Local leaders in East Tennessee have framed the project as another chance to expand what they call a unique regional nuclear ecosystem, which already includes legacy fission facilities, advanced reactor startups and university programs. In a statement circulated through national science channels, they described the ORNL partnership with Type One Energy and the University of Tennessee as “yet another opportunity to expand our unique East Tennessee nuclear ecosystem,” underscoring that the fusion campus is meant to attract talent and investment well beyond a single experiment. That regional framing matters, because it positions fusion not just as a distant climate solution but as an immediate economic engine for the communities around Oak Ridge.

Designing materials before reactors exist

Even with powerful testbeds, fusion materials research faces a chicken and egg problem. As ORNL scientists have put it, designing materials that are capable of surviving within a fusion reactor is a chicken and egg situation, because engineers cannot build a fusion power plant until they know which materials will last, but they cannot fully test those materials until a realistic environment exists. The lab’s own explanation of how MPEX will accelerate fusion energy stresses that designing and validating those materials requires purpose built plasma facilities that can mimic reactor conditions long before a commercial plant is online.

That is where the 10 MW heat tests become strategically important. By combining high power plasma sources with advanced diagnostics, ORNL and its partners aim to map exactly how candidate alloys, coatings and composites respond to the combined assault of heat, particles and mechanical stress. The work will draw on a broader network of fusion research sites, including international facilities and domestic labs such as the long running Princeton and Culham fusion centers, but it will focus on a niche that few other sites can match: sustained, reactor scale heat flux on full size components rather than small coupons.

More from Morning Overview