Uranus sits far beyond the orbit of Saturn, yet its smallest moons are suddenly at the center of a quiet revolution in outer solar system science. New observations suggest these tiny satellites are unusually dark, tinged red, and surprisingly poor in water ice, a combination that challenges long-held assumptions about how moons form and evolve in the deep cold. I want to unpack what that means for Uranus, for its family of moons, and for the broader story of how distant worlds are shaped by dust, radiation, and time.

Instead of behaving like miniature versions of the big icy satellites around Jupiter and Saturn, the small moons of Uranus appear to be carved from a different script, one written in carbon-rich material and sculpted by a harsh space environment. Their muted colors, skewed brightness patterns, and apparent lack of surface water hint at a complex history that stretches from the violent early days of the solar system to the subtle interplay of dust and light that continues today.

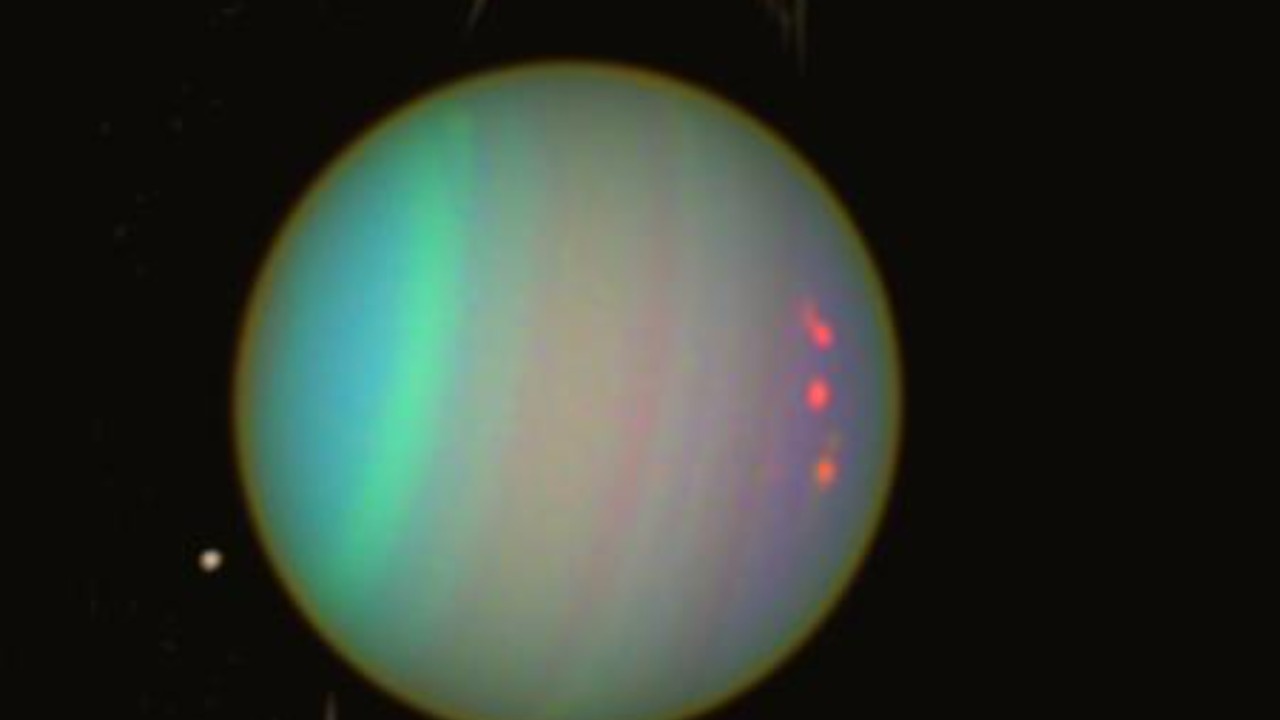

Uranus and its crowded, tilted system

Any attempt to understand the small moons of Uranus has to start with the planet’s strange architecture. Uranus is tipped on its side, with its rotation axis lying almost in the plane of its orbit, so its moons and rings circle in a plane that is effectively vertical compared with the rest of the solar system. That extreme tilt means seasons unfold in decades-long extremes of light and darkness, and the small moons spend large stretches of time either bathed in sunlight or plunged into shadow, a rhythm that shapes how their surfaces age and weather.

Despite its distance and odd orientation, Uranus is not a lonely world. According to current counts, Uranus has 28 known moons, a population that ranges from tiny inner satellites to five major bodies named Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. Those larger moons dominate most images and discussions, but the smaller companions that weave between the rings and the big satellites are increasingly important to scientists trying to reconstruct how the system assembled. Their orbits, sizes, and surfaces preserve clues about collisions, captures, and the long-term influence of Uranus’s tilted magnetic field.

From Voyager to modern telescopes: how we met the small moons

The first close look at Uranus and its moons came when the Voyager 2 spacecraft flew past the planet in the mid 1980s, providing humanity’s only in situ reconnaissance of this distant system. That single encounter revealed a handful of previously unknown satellites and sketched out the basic geography of the larger moons, but it left the smallest bodies as faint, unresolved points of light. In the decades since, ground-based observatories and space telescopes have had to pick up the slack, teasing out details from the limited light that reaches us across billions of kilometers.

As astronomers have pushed deeper, they have identified additional satellites and refined the orbits of the ones Voyager 2 first spotted. The current census of inner and outer moons, including Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon, is summarized in dedicated Uranus moon facts that also highlight how some of the more distant satellites are likely captured asteroids. That mix of native and captured bodies sets the stage for the small moons’ unusual appearance, since their raw materials may differ significantly from the ice-rich building blocks that dominate closer to the Sun.

Dark, red, and water-poor: what the new observations actually show

Recent observing campaigns have converged on a striking portrait of Uranus’s smaller moons as dim, reddish objects with surfaces that do not gleam with clean ice. Instead of the bright, reflective crusts seen on many of Saturn’s and Jupiter’s satellites, these bodies absorb much of the sunlight that hits them, making them appear dark in visible light. Their color trends toward red, a sign that complex organic molecules or space-weathered minerals may be coating their surfaces rather than fresh frost.

Spectral measurements indicate that these moons are also short on exposed water, at least at the surface, which is surprising in a region of the solar system where ice is expected to be abundant. Observers have described Uranus’s small moons as dark, red, and water-poor, a combination that suggests either that water ice is buried beneath a mantle of darker material or that the moons formed from a mixture with less ice to begin with. The same campaigns that characterize these properties also tie them to specific bodies, including Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon, as part of a broader effort to map how composition varies across the system, as detailed in new work on Uranus’s small moons.

Why being dark and red matters for moon formation

Color and brightness are not just aesthetic details, they are diagnostic tools that reveal what a moon is made of and how its surface has changed over time. A dark, red spectrum often points to carbon-rich compounds, sometimes called tholins, that form when simpler molecules are bombarded by ultraviolet light and charged particles. If Uranus’s small moons are coated in such material, it implies that their surfaces have been heavily processed by radiation and micrometeorite impacts, gradually transforming any original ices into a tougher, more complex skin.

The apparent lack of abundant surface water also feeds into debates about where these moons came from. If they formed in place from a disk of material around Uranus, their composition should reflect the balance of ice and rock in that disk, which might have been altered by the planet’s unusual tilt and thermal history. If some of them are captured objects, their darker, redder surfaces could echo the properties of distant asteroids or Kuiper Belt bodies that migrated inward. In either case, the combination of low albedo and reddish color suggests that the small moons are not simply scaled-down versions of Miranda or Ariel, but a distinct population shaped by different starting conditions and environmental forces.

Hubble’s “wrong side” mystery and the role of dust

Color and brightness are only part of the puzzle. Ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed that some of Uranus’s moons are darker on the side that faces forward in their orbit, a pattern that initially seemed counterintuitive. In many other systems, the trailing hemispheres of moons are darker because they sweep up debris from outer rings or dust clouds, but around Uranus the leading sides appear to be taking the bigger hit. That asymmetry hints at a complex interplay between the moons, the rings, and the planet’s environment.

Researchers analyzing these ultraviolet data have described the result as a dusty surprise, since the difference in brightness between hemispheres is larger than expected and appears on the “wrong” side compared with more familiar systems. The working explanation is that dust from Uranus’s rings and possibly from irregular outer moons spirals inward and preferentially strikes the leading faces of the inner satellites, gradually darkening them. This scenario is laid out in detail in studies of why Uranus’ moons are darker on the side that plows through this dusty environment, reinforcing the idea that ongoing surface gardening by tiny particles is a key driver of their appearance.

Water-poor surfaces in an ice-rich neighborhood

At Uranus’s distance from the Sun, temperatures are low enough that water ice should be stable on exposed surfaces, which makes the apparent scarcity of surface water on the small moons particularly intriguing. Spectra that show muted or absent water-ice signatures suggest that either the ice is hidden beneath a layer of darker material or that the moons’ outermost layers are dominated by non-icy components. Both possibilities carry important implications for how these bodies formed and how they have evolved under constant bombardment by dust and radiation.

If the ice is buried, then the dark, red mantle could be relatively thin, perhaps only a few meters to tens of meters deep, masking a more typical icy interior. In that case, impacts from micrometeorites or larger projectiles might occasionally punch through, exposing brighter patches that then gradually darken again. If, on the other hand, the moons are genuinely poor in water throughout, they may have formed from material that was already depleted in ice, perhaps because it condensed closer to Uranus where temperatures were slightly higher or because it was imported from a different region of the solar system. Either scenario underscores how the small moons complicate the simple picture of an outer solar system dominated by pristine ice.

Comparing Uranus’s small moons to its larger satellites

The contrast between the small moons and the five major satellites of Uranus is one of the most revealing aspects of the new observations. Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon are large enough to have experienced internal heating, tectonic activity, and in some cases resurfacing that brought fresher material to the exterior. Their surfaces, while not uniformly bright, show more evidence of water ice and geological diversity, suggesting a more active past that could have erased or diluted some of the darkening effects seen on the smaller bodies.

By comparison, the small moons lack the gravity and internal energy to reshape themselves in the same way, so whatever material lands on their surfaces tends to stay put and accumulate. That makes them more faithful recorders of the long-term bombardment by dust and radiation in the Uranian system. When I look at the emerging data, I see the larger moons as dynamic canvases that have been repainted multiple times, while the smaller satellites are more like archival photographs, preserving the slow, steady imprint of their environment. The fact that both populations orbit the same planet yet present such different faces is a powerful reminder that size and internal activity can dramatically alter how a world responds to the same external forces.

Captured asteroids or native children of Uranus?

One of the central questions raised by the small moons’ dark, red, water-poor surfaces is whether these bodies were born alongside Uranus or arrived later as interlopers. Some of the outer satellites of Uranus are already classified as likely captured asteroids, based on their irregular orbits and other dynamical clues. That possibility is explicitly noted in compilations of post-Voyager moons, which emphasize that several distant companions probably did not form in the same disk of material that produced the inner satellites and rings.

If some of the small inner moons share a similar origin, their dark, reddish surfaces could be a natural inheritance from parent bodies that once orbited the Sun independently, perhaps in the asteroid belt or beyond. Alternatively, they might be fragments of larger moons that were shattered by collisions, with the debris reassembling into smaller, irregular satellites that inherited a mix of ice and rock. In either case, the current observations do not yet provide a definitive answer, but they do narrow the possibilities by ruling out the simplest scenario in which all of Uranus’s moons formed from a uniform, ice-rich disk and then evolved in lockstep.

What Uranus’s small moons can teach us about other systems

Although the details are specific to Uranus, the broader lessons from its small moons reach far beyond this one planet. Many giant planets, both in our solar system and in exoplanetary systems, are likely to host swarms of small satellites and ring particles that interact through dust, radiation, and gravity. The way Uranus’s tiny moons have been darkened, reddened, and stripped of visible water offers a template for how similar processes might operate elsewhere, especially around worlds that are tilted, magnetically complex, or embedded in dense debris fields.

For planetary scientists, these moons are natural laboratories for studying space weathering, surface chemistry, and the long-term evolution of small bodies in harsh environments. Their properties can help refine models of how dust migrates through ring systems, how radiation alters organic molecules, and how collisions redistribute material among moons and rings. As I see it, every new constraint on the composition and appearance of these satellites feeds directly into our understanding of how planetary systems age, not just in the outer reaches of our own solar system but around distant stars where similar dynamics may be playing out unseen.

The case for a dedicated Uranus mission

All of this emerging detail about Uranus’s small moons has been extracted from a limited set of observations, many of them at the edge of what current telescopes can resolve. Voyager 2 provided a crucial first snapshot, but it was a brief flyby, not a long-term survey, and it left many of the smallest satellites as little more than smudges on a detector. To truly understand why these moons are so dark, so red, and so apparently short on water, a dedicated mission that can linger in the Uranian system is needed.

Such a mission could map the surfaces of the small moons at high resolution, measure their compositions across a wide range of wavelengths, and track how dust and charged particles move through the system in real time. It could also probe the interiors of the larger moons, search for signs of past or present activity, and test whether the small satellites are fragments, captures, or native children of Uranus. Until that happens, astronomers will continue to push existing tools to their limits, but the tantalizing hints we already have make a strong case that the next great leap in outer solar system exploration should point toward this tilted, crowded, and unexpectedly complex world.

More from MorningOverview