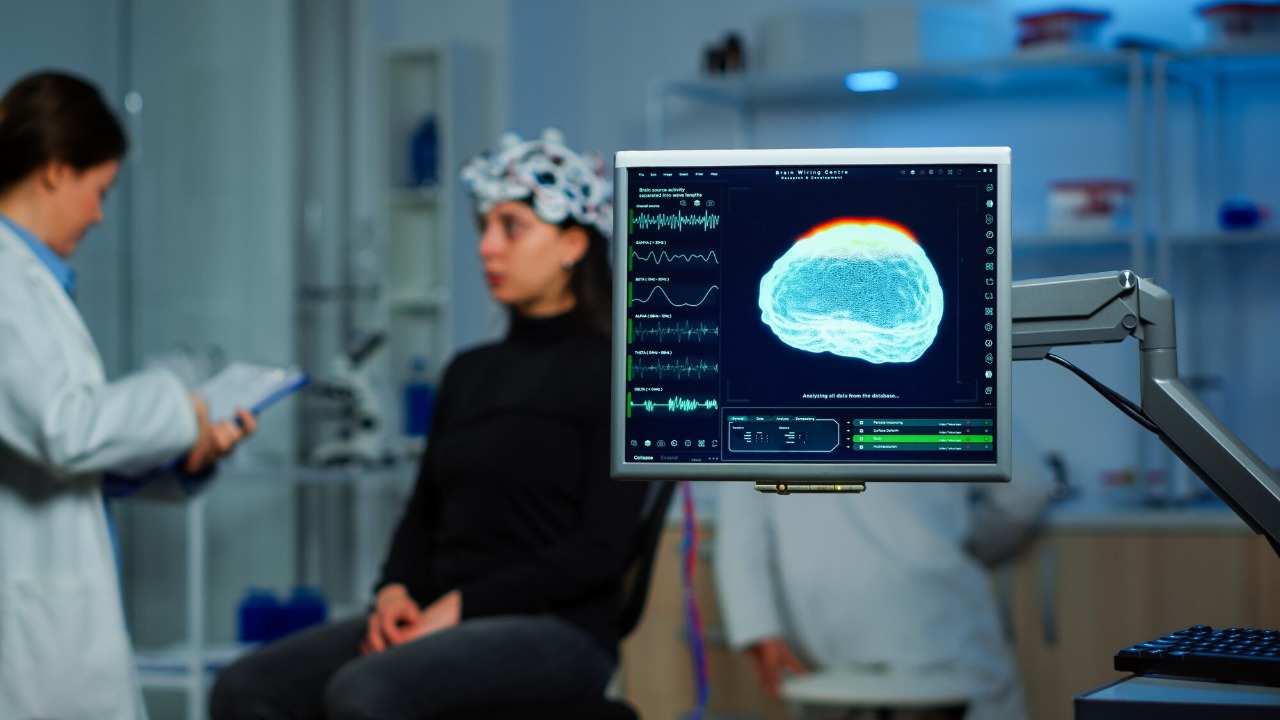

A helmet that looks more like sports gear than surgical equipment is quietly rewriting what is possible in brain medicine. By steering pulses of sound through the skull, the device can reach deep structures that once required drilling holes and implanting electrodes, offering a new way to modulate brain circuits without a single cut. For patients facing Parkinson’s disease, severe tremor, depression or Tourette syndrome, that shift could turn a life‑altering operation into something closer to an outpatient fitting.

From operating theater to wearable tech

For decades, deep brain stimulation has meant neurosurgeons threading metal leads into tiny targets like the subthalamic nucleus, then wiring them to a pacemaker in the chest. The new ultrasound helmet keeps the same ambition, precise control of deep circuits, but swaps hardware for focused sound waves that pass harmlessly through bone. Researchers describe a system that wraps around the head and uses dozens of individually controlled emitters to concentrate energy on millimeter‑scale regions, creating a kind of programmable, noninvasive deep brain stimulator that can be adjusted in real time, as outlined in early reports.

Teams at University College London and the University of Oxford have pushed this approach further by building a helmet that can stimulate deep nuclei that previous ultrasound systems struggled to reach with enough precision. They note that earlier devices often lost focus or could not reliably hit small structures, a limitation the new array is designed to overcome, according to technical details shared by Oxford researchers. At the core of the design is transcranial ultrasound stimulation, or TUS, a technique that has been refined in a recent study to deliver deep neuromodulation without sacrificing focal precision.

How focused sound reaches deep brain targets

The physics behind the helmet is deceptively simple: ultrasound beams, similar to those used in prenatal scans, are steered and timed so they intersect at a chosen point inside the brain, where their energy adds up. Outside that focal spot, the intensity remains low, which is why the surrounding tissue is spared. In the latest TUS system, described in an Abstract, engineers solved a long‑standing trade‑off by shaping the beam so it can penetrate deeply without losing its tight focus, a prerequisite for hitting structures only a few millimeters across.

That capability matters because many neurological and psychiatric disorders trace back to small hubs buried in the brain. The new helmet has already been used to selectively stimulate a deep brain nucleus in humans without surgery, according to a description of a helmet‑shaped device tested by teams at University College London (UCL) and the University of Oxford in a clinical report. In one experiment, another group showed that changes in visual cortex activity persisted for 40 m after stimulation, suggesting that even brief sessions can leave measurable, short‑term footprints in brain activity.

What early human tests are showing

Early trials are small, but they are already offering a glimpse of what noninvasive deep brain stimulation might look like in practice. In one study, Researchers tested the helmet on seven people by targeting a part of the thalamus, a small structure in the brain’s center that relays sensory information, and monitored how stimulation changed their responses, according to a summary of the work by Researchers. A separate News Article by Morgan Roberts of University College London described how participants tolerated the sessions without serious side effects, reinforcing the idea that the approach can be both targeted and safe in the short term, as noted in the News Article.

In parallel, another group of scientists reported that a new ultrasound helmet might be able to precisely stimulate areas deep in the brain without the need for surgery, positioning it as a potential alternative to implanted deep brain stimulation systems, according to a summary of work published in Nature Communications that was highlighted in a News brief. The same report emphasized that But a new ultrasound helmet might be able to precisely stimulate areas deep in the brain without the need for surgery, a point reiterated in a follow‑up note that But a new ultrasound helmet might be able to precisely stimulate areas deep in the brain without the need for surgery, according to a description of the Nature Communications paper cited in a later update.

Why clinicians see a “paradigm shift” coming

For neurologists, the appeal of the helmet is not just that it avoids the scalpel, it is that it could turn brain stimulation into something adjustable, repeatable and personalized. The new ultrasound system offers a non-invasive alternative with comparable precision, potentially allowing clinicians to test areas before committing to long‑term treatment and to move toward closed loop neuromodulation and personalised therapies, according to technical commentary on the new system. One researcher quoted in coverage of the work put it bluntly, saying the ultrasound is being used to safely, transiently and non-invasively change the activity in the brain cells (neurons), a description that captures why some are calling the device a paradigm shift for neuroscience, as reported in a feature.

Outside the lab, digital health commentators are already sketching out what that future might look like. Let’s start the week with some good news, wrote Bertalan Meskó, MD, PhD, who argued that an ultrasound helmet could replace deep brain stimulation and may also help with Toure syndrome, highlighting the work of Jesús Santaliestra in a widely shared post. A separate explainer on focused ultrasound in the brain by Tejas Padliya describes how Focused ultrasound, or FUS, can concentrate energy on a tiny spot, reinforcing why clinicians see this as a flexible platform rather than a single‑use gadget, as detailed in a technical overview of FUS.

Parkinson’s, tremor and beyond

The most immediate clinical target for the helmet is Parkinson’s disease, where implanted deep brain stimulators are already standard for patients whose symptoms no longer respond to medication. A pioneering ultrasound “helmet” could transform Parkinson’s treatment by non-invasive stimulation, with early reports pointing to significant tremor control lasting for years in patients treated with focused ultrasound, according to a widely shared summary. A separate video explainer frames the same technology as a potential breakthrough in medical science that promises to fundamentally alter how Parkinson’s disease is cured, underscoring how quickly expectations are rising around the new device, as described in a Parkinson explainer.

Researchers are also eyeing conditions that have been harder to treat with surgery. One overview notes that the helmet could one day help with conditions such as Parkinson’s without invasive surgery, reflecting scientists’ cautious optimism that the same circuits implicated in movement disorders might be tuned with sound rather than metal, as described in a feature. Another social media discussion of the work notes that The article describes a new ultrasound helmet that can target specific areas of the brain without surgery, emphasizing that the helmet uses focused sound to reach areas of the brain without incisions, as summarized in a neuroscience discussion.

More from Morning Overview