Engineers in the United Kingdom are racing to build metal shields that can survive conditions similar to the center of the Sun, a prerequisite if fusion power is ever going to move from experiment to grid. The latest push focuses on “super strong” alloys and advanced manufacturing that can withstand searing heat, violent particle bombardment, and relentless mechanical stress inside future reactors. The work is no longer just about proving physics, it is about turning fusion into a commercial reality by making the hardware tough enough to last.

That shift is pulling together university labs, national facilities and private firms around a shared goal: materials that can sit just millimeters from plasma hotter than the Sun and keep performing for years. From new tungsten structures to ultra‑resistant “first wall” alloys and AI tools that predict how metals fail, the UK is trying to lock in an edge in the global fusion race by solving the brutal materials problem first.

Why fusion needs “sun-proof” walls

At the heart of every magnetic fusion concept is a paradox: the plasma must be heated to temperatures hotter than the Sun, yet nothing solid can be allowed to touch it. In practice, particles and heat still slam into the inner lining of the reactor, so the first components to face the onslaught must be built from materials that behave almost like artificial rock, shrugging off thermal shocks that would shred conventional steel. Engineers have long known that the structural metals surrounding a fusion plasma will see extreme temperatures and neutron damage that cannot be handled by traditional welding or casting, which is why UK teams are now developing new alloys and architectures from the ground up.

The ambition is to create UK‑made super strong materials that can shield fusion reactors from heat comparable to the center of the Sun, while also resisting the way high‑energy neutrons knock atoms out of place and make metals brittle. Researchers working on these UK‑made materials frame them explicitly as a bridge to “commercial reality” for fusion, arguing that without such protection, even the most advanced plasma devices would be too fragile and too expensive to operate as power plants.

From lab alloys to industrial manufacturing

Designing a miracle metal in a computer model is one thing, turning it into kilometers of reactor components is another. Earlier this year, a new UK research initiative was announced on a Thursday to explore how to manufacture materials for extreme fusion environments at scale, with a particular focus on components that must survive complex conditions including extreme temperatures and intense radiation. The program, led from Nottingham, is intended to connect fundamental metallurgy with industrial processes so that the exotic alloys needed for fusion do not remain stuck in small test coupons, and its launch was set out in detail by the Nottingham team.

One of the most promising routes is advanced 3D printing of metals, which allows engineers to tune microstructures layer by layer. The UK Atomic Energy Authority, described as a government‑funded research organization, has already demonstrated that it can use additive manufacturing to create complex geometries and novel chemistries that would be impossible with conventional casting, a capability highlighted in a project that invited readers to Share this Article on new 3D printed metal alloys for nuclear fusion. That work is tightly coupled to the broader UK push on super strong reactor materials, which is also profiled in a separate report on engineers developing shields for fusion devices.

Tungsten, ultra-resistant alloys and the “first wall”

Among candidate materials, tungsten has emerged as a workhorse for the hottest zones of a reactor, thanks to its very high melting point and good thermal conductivity. UK fusion reactors are now set to receive super strong tungsten components produced with an eMELT device that uses electron beam powder bed fusion, a form of additive manufacturing described as (E‑PBF) technology, to build intricate structures that can better handle thermal stress. The effort to equip UK fusion reactors with this super strong tungsten is framed as a way to beat extreme heat rather than simply survive it.

Beyond tungsten, researchers are targeting the so‑called “first wall”, the inner surface that faces the plasma and must endure the harshest conditions. Work on ultra‑resistant alloys for this region is being tested under realistic reactor‑like conditions, with teams in Germany and elsewhere focusing on combinations of conventional refractory metals and emerging high‑entropy alloys that can resist cracking and erosion. One detailed account of these new alloys stresses that building materials for extreme fusion conditions means designing metals that do not become brittle under neutron bombardment, a point echoed in a separate report on Building materials for future reactors.

The idea of igniting a star on Earth is central to fusion’s appeal, and it is precisely that vision that makes the first wall such a critical engineering challenge. One analysis of how the first wall is being upgraded describes it as Built for extreme heat, combining ultra‑resistant alloys and high‑entropy compositions to create a “sun‑proof” barrier. A complementary report on Nuclear fusion reactor walls underscores that these materials are being tested under realistic reactor‑like conditions rather than only in small laboratory setups.

Modeling metals and taming hotter-than-Sun plasmas

Even the toughest alloy will fail if engineers misjudge how it behaves under decades of thermal cycling and neutron bombardment, which is why detailed modeling of metal performance has become a parallel priority. A team led by Giacomo Po in the UK, working with international partners, has been modeling how metals perform under extreme heat to help bring fusion power closer to reality, noting that the challenge has always been keeping the plasma stable and contained long enough for a sustainable reaction. Their work, described in a report on Giacomo Po’s team, feeds directly into how new alloys are specified and where they are deployed inside a reactor vessel.

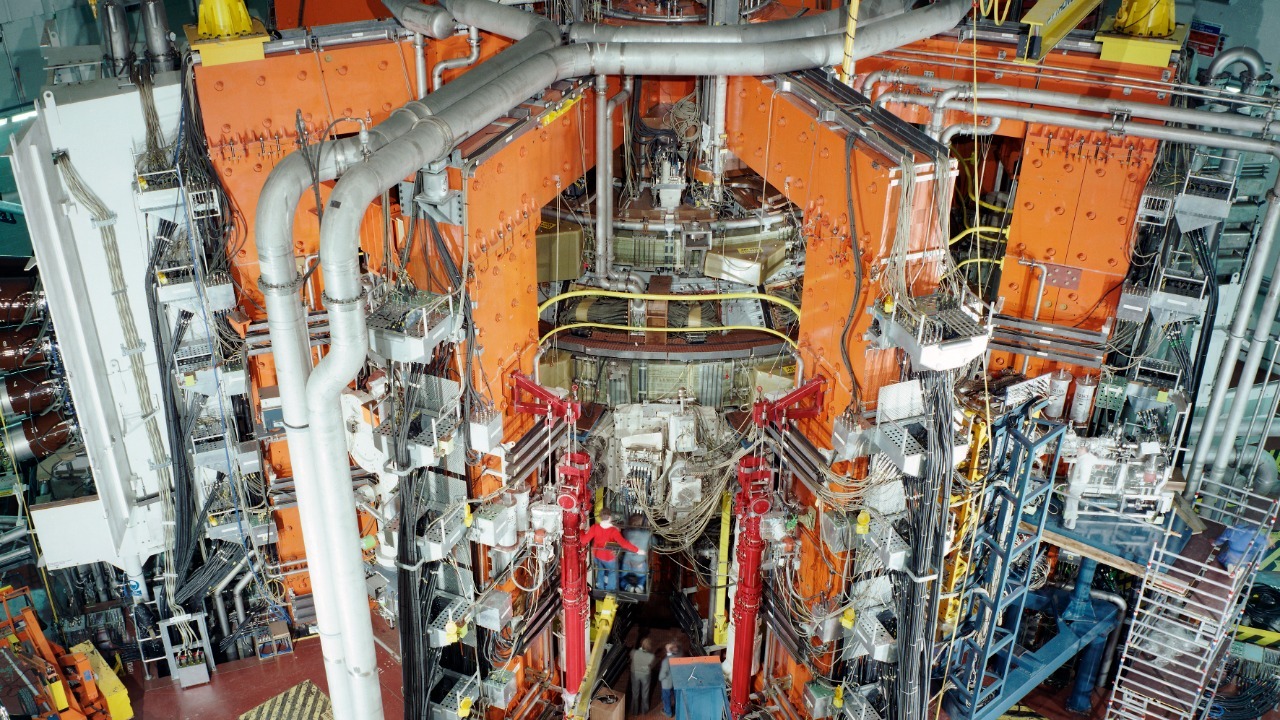

On the plasma side, UK scientists are also pushing devices that can generate conditions even more extreme than the Sun in a controlled way. At the UK, Culham Campus, a Machine has been used to create plasma hotter than the Sun and to tackle one of fusion energy’s biggest problems, namely how to confine that plasma without damaging the surrounding structure, a milestone described in detail in a report that notes how the Machine brings fusion closer to real‑world use. That work is complemented by the UK’s MAST Upgrade machine’s fifth Campaign, which is underway to lay foundations for fusion power plant development and to test new methods for heating the plasma, as described in detail in an update on the MAST Upgrade Campaign.

Artificial intelligence is starting to accelerate this loop between plasma physics and materials science. Researchers from the United Kingdom and Austria have developed an AI tool called GyroSWin that can speed up the modeling of plasma turbulence, a breakthrough described in a report on Researchers from the United Kingdom and Austria. A separate account by Jon Turi notes that scientists see this kind of advance as “something that feels within reach”, especially because fusion fuel could be sourced from abundant seawater supplies, a point highlighted in a piece credited to Jon Turi. Together, these tools help match plasma behavior to material limits, so that “sun‑proof” walls are not over‑ or under‑engineered.

Positioning the UK in the global fusion race

Behind the technical work sits a strategic calculation about where the UK wants to sit in the emerging fusion economy. A recent analysis argued that the country must change its approach if it wants to win the fusion race, with First Light Fusion and Stonehaven calling for inertial fusion energy to be incorporated into the UK’s research and regulatory framework so that the nation can become one of the best places in the world to build fusion capability. That argument, set out in detail in a report featuring First Light Fusion, explicitly links regulatory clarity to investment in advanced materials and manufacturing.

More from Morning Overview