High above Antarctica, two giant NASA balloons are being readied to drift along the edge of space, turning the polar sky into a laboratory for some of the hardest questions in physics. Instead of rockets, these missions rely on thin film envelopes the size of stadiums to hoist cutting edge instruments into the stratosphere, where the air is thin, the view of the cosmos is clear, and the costs are a fraction of an orbital launch. Their targets are elusive, from ghostly neutrinos to hints of dark matter, but the strategy is straightforward: ride the polar winds for weeks and scoop up the rarest signals the universe has to offer.

By returning to Antarctica with a pair of long duration flights, NASA is betting that balloons can do more than serve as test beds, they can deliver frontline astrophysics. The two missions, including the General AntiParticle Spectrometer and a neutrino focused experiment, are designed to chase cosmic secrets that satellites and ground based observatories struggle to catch, using the unique environment over the southern ice to stretch observing time and scientific ambition.

NASA’s Scientific Balloon Program heads south again

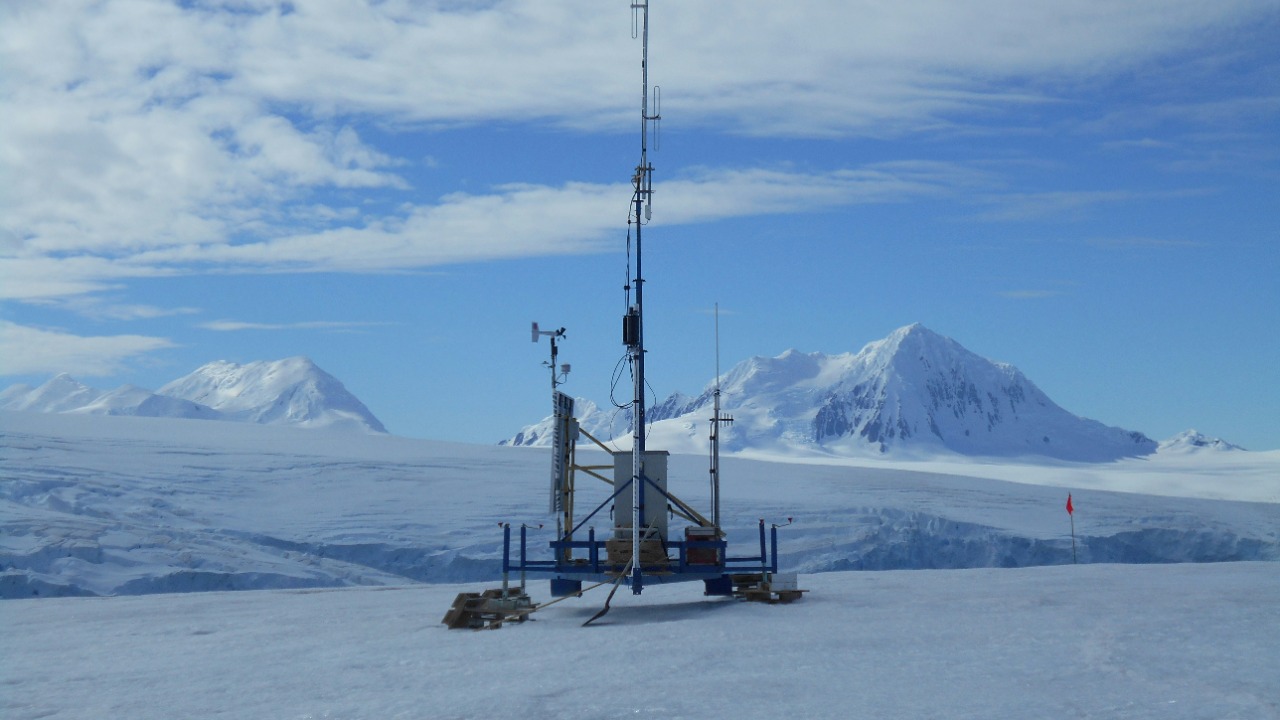

NASA is sending its Scientific Balloon Program back to Antarctica for another long campaign, a sign that high altitude balloons have become a core part of the agency’s astrophysics toolkit rather than a niche side project. The latest deployment involves two separate flights that will share the same polar staging grounds but pursue different slices of the cosmic puzzle, one centered on antimatter and the other on ultra high energy particles that barely interact with ordinary matter. By returning to the same region year after year, the program is building a kind of seasonal observatory in the sky, tuned to the southern summer when constant daylight and stable winds make these marathon flights possible.

The scale of the effort is striking. According to NASA, its Scientific Balloon Program is back in Antarctica for a long duration campaign that will loft instruments capable of probing sources billions of light years away, all from a platform that floats rather than orbits. The same effort is highlighted in the broader archive of Two NASA Scientific Balloon Launches Planned From Antarctica, which underscores how these flights extend the reach of NASA’s Columbia Scientific Balloon operations into the polar regions. Together, the two balloons turn Antarctica into a launch pad for experiments that would be prohibitively expensive to fly on dedicated satellites.

Why Antarctica is the perfect launchpad

Antarctica might seem like an unlikely place to chase the cosmos, but for balloon scientists it is close to ideal. During the austral summer, the Sun never sets, which keeps the stratosphere warm and the winds relatively steady, allowing balloons to circle the continent for weeks without dipping into darkness or losing altitude. That constant daylight is crucial for the solar panels that power the instruments, and the stable wind patterns act like a slow motion racetrack, letting the payloads trace long loops over the ice while ground teams track them from a safe distance.

The environment also offers practical advantages that are hard to match elsewhere. Launch crews can spread out on the Antarctic ice, giving the enormous envelopes room to inflate and rise without threatening nearby communities, and recovery teams can plan for landings on relatively predictable ice fields instead of dense forests or populated areas. As NASA’s own coverage of Antarctica for its Scientific Balloon Program makes clear, the continent’s isolation is not a bug but a feature, turning a harsh landscape into a controlled test range for instruments that need both altitude and time to do their work.

Football stadium sized giants in the polar sky

The balloons themselves are feats of engineering, more like flying architecture than party decorations. When fully inflated, each envelope can reach the size of a football stadium, a thin shell of plastic that must withstand extreme cold, intense sunlight, and the constant tug of the payload hanging beneath it. From the ground, the launch looks almost surreal, a vast translucent dome slowly rising from the ice, carrying a gondola packed with detectors, electronics, and communications gear that will operate in near vacuum conditions at the edge of space.

Scientists with NASA have described how these enormous balloons, the size of a football stadium, are launched from the Antarctic ice and filled with enough helium to lift heavy scientific payloads into the stratosphere, a process detailed in coverage of Scientists with NASA launching these football stadium sized balloons. The sheer volume of gas required, and the precision needed to keep the envelope intact as it expands in the thin air, illustrate why these flights demand months of preparation and highly specialized crews. Yet once aloft, the balloons become remarkably stable platforms, drifting quietly while the instruments below them listen for faint whispers from the universe.

GAPS: hunting dark matter with antimatter clues

One of the two flagship missions is GAPS, short for General AntiParticle Spectrometer, which is designed to search for subtle traces of dark matter by looking for the antimatter it might leave behind. Instead of trying to see dark matter directly, GAPS focuses on low energy cosmic ray particles that could be produced when dark matter particles annihilate each other, a kind of forensic approach that treats the stratosphere as a giant detector volume. By flying high over Antarctica, the instrument can sift through a cleaner stream of cosmic rays than it would encounter closer to the ground, where Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field scramble the signals.

The mission’s technical focus is unusually specific. As the project’s own description notes, GAPS (General AntiParticle Spectrometer) is an Antarctic balloon mission designed to search for low energy, less than 0.25 G, cosmic ray antideuterons, antiprotons, and antihelium, particles that could signal exotic processes in the dark matter sector. That focus on rare antimatter species makes GAPS a kind of cosmic customs agent, scanning for contraband particles that standard astrophysical sources struggle to produce in significant numbers. If it finds even a handful of these low energy antideuterons, the result would ripple across particle physics and cosmology, forcing theorists to revisit models of what dark matter is and how it behaves.

PUEO and the hunt for ghostly neutrinos

Complementing GAPS is The PUEO mission, which targets a very different kind of quarry, ultra high energy neutrinos that can pass through entire planets without leaving a trace. Where GAPS looks for charged particles that can be bent and filtered by magnetic fields, PUEO is tuned to catch the faint radio signals produced when a neutrino finally does interact in the ice, a rare event that carries information about some of the most violent phenomena in the universe. By flying above Antarctica, the instrument can scan vast swaths of the ice sheet, turning the continent itself into part of the detector.

The PUEO mission is notable not just for its science goals but for how it fits into NASA’s broader strategy. Reporting on the long duration Antarctic balloon campaign explains that The PUEO mission is the first balloon borne project selected under NASA’s Astrophysics Pioneers program, which supports relatively low cost, high impact experiments that can be developed and flown on shorter timelines than traditional flagship observatories. In the same campaign, the GAPS experiment will investigate dark matter signatures while the balloons carry heavy scientific payloads, showing how a single Antarctic season can host multiple frontier experiments. Together, PUEO and GAPS turn the polar sky into a shared platform for probing both the invisible matter that shapes galaxies and the neutrinos that trace the universe’s most extreme accelerators.

How long duration balloon flights rival satellites

What makes these Antarctic flights so powerful is not just their altitude but their endurance. Long duration balloons can stay aloft for weeks, sometimes more than a month, giving instruments a continuous view of their targets that rivals or even exceeds what some satellites can offer in specific observing modes. For experiments like GAPS and PUEO, which are chasing rare events and low flux signals, time is as valuable as height, every extra day in the stratosphere increases the odds of catching something extraordinary.

NASA’s own planning documents for Scientific Balloon Program flights from Antarctica emphasize that these long duration campaigns are designed to maximize data collection while the balloons circle the continent, effectively turning each mission into a mobile observatory. Unlike satellites, which must contend with orbital mechanics, station keeping, and long term radiation exposure, balloons can be tailored to a specific season and then recovered, refurbished, or replaced as needed. That flexibility allows NASA to iterate on instrument designs more quickly, incorporate lessons from each flight into the next, and keep the cost per mission relatively low compared with launching hardware into orbit.

Zero pressure workhorses and piggyback missions

Underpinning this strategy are the zero pressure balloons that serve as the workhorses of the Antarctic campaigns. These envelopes are designed to vent gas as they warm and expand, keeping internal pressure close to the surrounding atmosphere and reducing stress on the material. The result is a platform that can float at a nearly constant altitude for long stretches, even as temperatures and solar heating change over the course of a day. For scientists, that stability translates into cleaner data and fewer surprises, which is especially important for experiments that depend on precise calibrations and long integrations.

Those same zero pressure designs also make room for smaller experiments to hitch a ride. Coverage of NASA’s Scientific Balloon Flights to Lift Off From Antarctica explains that Piggyback Missions use NASA’s zero pressure balloons, capable of lifting up to 8,000 pounds, to carry multiple smaller piggyback experiments that can collect significant data while circling the continent. That 8,000 pounds capacity turns each launch into a shared platform, where student built instruments, technology demonstrations, and secondary science payloads can fly alongside headline missions like GAPS and PUEO. In practical terms, it means that every Antarctic campaign seeds a broader ecosystem of research, training the next generation of scientists and engineers while squeezing more science out of every cubic meter of helium.

From travel news to frontier physics

To an outsider, the idea of balloon launches from Antarctica can sound almost like an exotic travel feature, a quirky story about scientists camping on the ice and watching giant envelopes rise into the polar sky. There is a tourism angle, in the sense that these flights have become notable enough to appear in travel focused coverage that highlights the spectacle of launches and the logistical ballet required to support them. Yet beneath that surface level fascination lies a serious scientific agenda, one that treats the Antarctic plateau as a gateway to the high energy universe rather than a remote backdrop.

Reports on NASA Scientific Balloon Flights to Lift Off From Antarctica describe how two balloon flights will carry major experiments like GAPS (General Anti-Particle Spectrometer) while also supporting multiple smaller piggyback experiments, blending frontier physics with a kind of airborne research campus. That mix of flagship and secondary payloads shows how the same infrastructure that captures public imagination can also deliver hard science, from dark matter searches to atmospheric studies. For me, the most striking part of this story is how a platform that once seemed quaint compared with rockets has quietly become one of the most versatile tools in NASA’s astrophysics arsenal.

Why balloons still matter in the space age

In an era dominated by reusable rockets and mega constellations of satellites, it might be tempting to see balloons as a relic of an earlier phase of space exploration. The Antarctic campaigns argue the opposite. By pairing modern detectors with mature balloon technology, NASA is carving out a niche where high risk, high reward science can flourish without the price tag or lead time of a full satellite mission. That niche is especially valuable for experiments like GAPS and PUEO, which push into parameter spaces that are still speculative and might not yet justify a billion dollar observatory.

The recurring presence of the Scientific Balloon Program in Antarctica, and the way it is woven through the Two NASA Scientific Balloon Launches Planned From Antarctica archive, underscores that this is not a one off stunt but a sustained strategy. By treating the polar sky as a recurring test bed, NASA can iterate quickly, share lift capacity across multiple teams, and respond to new theoretical ideas with hardware that can be built and flown on human, rather than generational, timescales. In that sense, the two balloons now heading to Antarctica are not just chasing cosmic secrets, they are also charting a path for how space science can stay nimble in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

More from MorningOverview