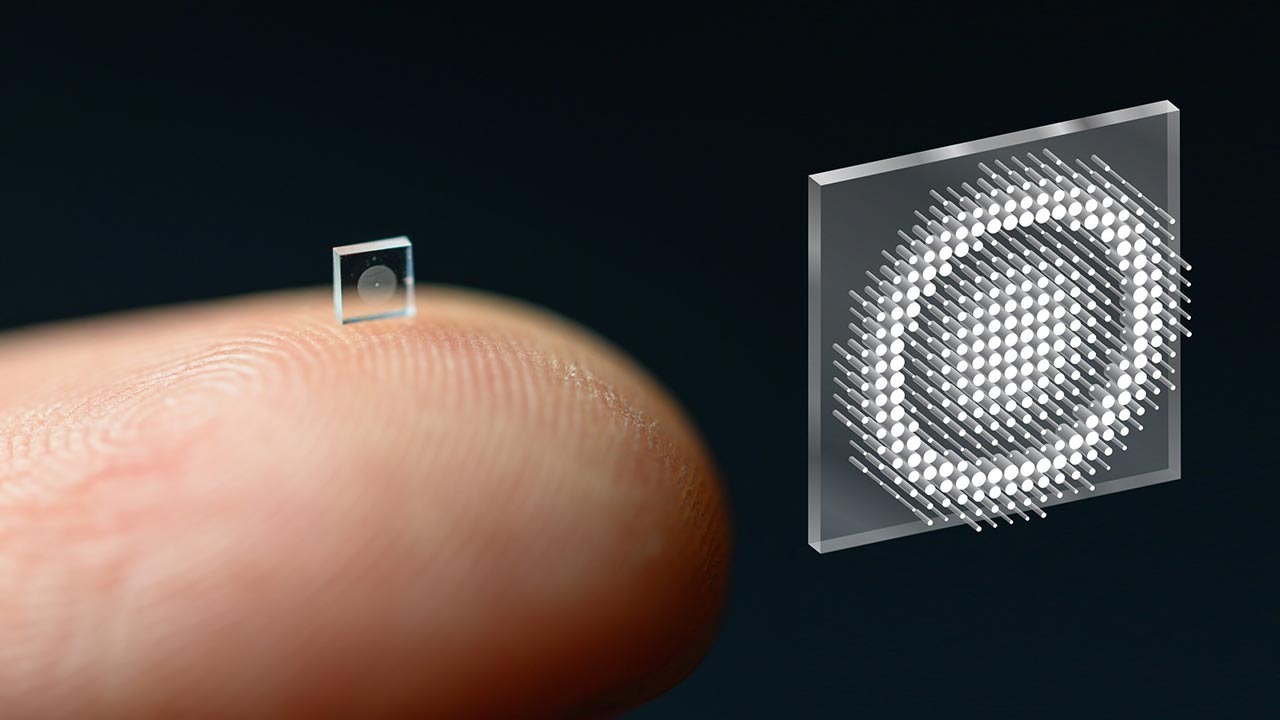

A tiny optical booster built directly onto a chip is pointing toward a future where light, not just electricity, does the heavy lifting inside our computers. By cranking up light signals roughly 100 times while barely sipping energy, it promises faster data movement, cooler hardware, and new headroom for artificial intelligence and communications without the usual power penalty.

Instead of relying on bulky external amplifiers, this approach folds a powerful light intensifier into the same kind of silicon platform already used in laptops and smartphones. If it scales, the result could be compact processors that move and process information with light, reshaping everything from cloud data centers to edge devices in cars and home assistants.

How The Stanford chip turns a trickle of light into a torrent

The core breakthrough comes from a chip-scale optical amplifier that can strengthen a weak light signal by a factor of about 100 while using almost no additional energy. I see that as a direct challenge to the long-standing tradeoff in photonics, where boosting signal strength usually means adding bulky hardware or burning significant power. Here, the device is integrated into a chip-scale platform, which means the amplifier can sit right next to logic and memory circuits instead of living in a separate optical box on a lab bench.

The Stanford team built this amplifier so it can be fabricated with processes compatible with the chips already found in consumer electronics, which is why references to laptops and smartphones matter. By keeping the design aligned with mainstream manufacturing, they are not just demonstrating a physics experiment, they are laying groundwork for commercial integration. The fact that this work is attributed to The Stanford group, with the result highlighted in Jan, signals that the research community is treating this as a timely step toward practical, light-based computing blocks.

Why light is becoming the new workhorse for AI chips

Optical amplification on a chip matters because AI workloads are increasingly limited by how fast and efficiently data can move, not just how many arithmetic operations a processor can perform. Earlier work from a team of engineers showed that using light instead of electricity for one of the most common AI operations, convolution, can make a chip dramatically more efficient. In that design, the researchers used an optical architecture to perform convolutional processing for neural networks, and the result was a new kind of that offloads a key AI building block into the optical domain.

Another group of Researchers pushed this idea further by combining light with electricity on a silicon chip to execute convolution operations with far higher energy efficiency than conventional electronics. They framed the work explicitly in terms of sustainability, arguing that optical computation can cut the power draw of AI systems that now strain data center cooling and regional power grids. When I connect those dots to The Stanford amplifier, the picture that emerges is a stack of optical components, from compute blocks to signal boosters, that can be mixed and matched to build full photonic accelerators.

From lab demos to 100x-class performance gains

Performance numbers around optical AI hardware are starting to sound less like incremental tweaks and more like generational leaps. One light-powered AI chip developed by a team in Sep was described as making AI tasks roughly 100 times more efficient by exploiting optical convolution, which aligns with the broader trend of using photonics to sidestep the thermal and bandwidth limits of electrons. That kind of efficiency gain is not just a benchmark trophy, it is the difference between running a large model on a battery-powered device and having to ship every query to a remote server farm.

On the speed side, researchers from Shanghai reported a light-powered AI chip that is described as 100x faster than a top NVIDIA GPU for certain tasks. But most advances before that had been limited to simpler workloads like image classification or text generation, and now the focus is shifting toward more complex operations that better reflect real-world AI deployments. I read the Stanford amplifier as a complementary piece: if you want to sustain 100x-class speedups across a full system, you need a way to keep optical signals strong and clean as they traverse increasingly dense on-chip networks.

China’s ‘LightGen’ and the global race for all-optical hardware

The Stanford amplifier is arriving in a landscape where national research programs are already betting heavily on all-optical chips. In one prominent example, China has developed an all-optical chip called LightGen that is described as 100 times faster than NVIDIA chips for AI-style workloads. Traditional electronic chips like NVIDIA hardware are constrained by how quickly electrons can move through metal interconnects and how much heat they generate, while LightGen uses light to mimic aspects of the human brain with far lower latency and higher parallelism.

That project is tied to a formal scientific publication, with a reference to the identifier 10.1126 in the reporting, which signals that the work has been vetted in a peer-reviewed context rather than only in a press release. When I compare LightGen to The Stanford amplifier, I see two sides of the same race: national-scale initiatives building full all-optical processors, and university labs refining the building blocks that can be slotted into those architectures. Both depend on reliable, low-energy ways to strengthen and route light on a chip, which is exactly the niche this new amplifier aims to fill.

What it will take to move optical boosters into everyday devices

For all the impressive numbers, the path from lab prototype to everyday hardware still runs through manufacturing, software, and standards. The Stanford amplifier is explicitly designed to be compatible with the same fabrication flows used for consumer chips, which is why its potential use in devices like smartphones is more than a throwaway line. To reach that point, chipmakers will need to integrate optical waveguides, amplifiers, and detectors alongside transistors without wrecking yields or driving up costs, a challenge that has slowed earlier photonics efforts.

On the software side, AI frameworks and compilers will have to learn how to target heterogeneous hardware that mixes electronic cores, optical accelerators, and on-chip light boosters. The earlier Sep work on optical convolution chips and the Shanghai team’s 100x GPU-class accelerator show that researchers are already mapping neural network operations onto photonic fabrics, but those mappings are still specialized. I expect the next phase to focus on standard interfaces so a model trained in PyTorch or TensorFlow can automatically exploit an optical path when it is available, with the amplifier quietly doing its job in the background to keep light signals strong without blowing the power budget.

More from Morning Overview