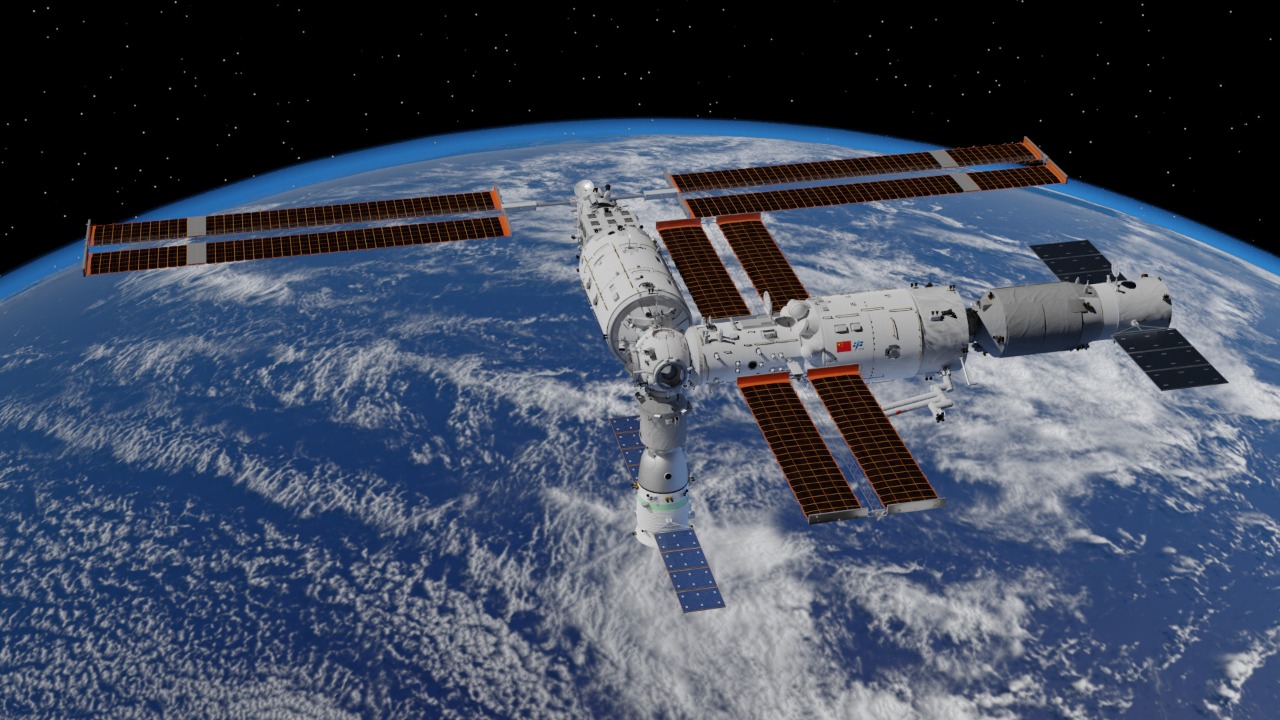

Three Chinese astronauts are once again stuck aboard the Tiangong space station, this time after a dramatic rescue of their predecessors exposed just how fragile the country’s crewed access to orbit really is. As I trace how one damaged return capsule led to a second crew being stranded, the story that emerges is less about a single mishap and more about the growing risks of flying through an increasingly cluttered low-Earth orbit.

From the first reports of debris striking a Shenzhou spacecraft to the latest updates that the current crew is safe but without a certified ride home, I keep coming back to the same uneasy question: how many times can a space program roll the dice on orbital junk before luck runs out? The answer matters not just for China’s taikonauts, but for every astronaut, satellite operator and space agency sharing the same crowded lanes above our heads.

How one damaged capsule led to another stranded crew

The chain of events began when a piece of space debris hit the Shenzhou return capsule that was supposed to bring three Chinese astronauts safely back from Tiangong. According to detailed accounts, the impact compromised the vehicle’s heat shield and other critical systems, making it too risky to attempt a fiery plunge through Earth’s atmosphere. Engineers on the ground concluded that the capsule could no longer guarantee a survivable reentry, effectively trapping the crew in orbit while they scrambled for alternatives, a scenario first described when three taikonauts were stranded after debris hit their return capsule.

To avoid leaving the astronauts in limbo indefinitely, mission controllers prioritized launching a fresh Shenzhou spacecraft that could serve as an emergency lifeboat. That rescue flight ultimately succeeded in ferrying the original crew back to Earth, but it came at a cost: the vehicle that had been earmarked for the next rotation was pulled forward, leaving the subsequent trio without a backup ride. When the next expedition launched to Tiangong, they did so knowing that the usual redundancy had been consumed by the earlier emergency, a trade-off that set the stage for three more taikonauts to be stranded following the successful rescue of their colleagues.

The first rescue: bringing the earlier crew safely home

Before the current predicament, the focus was on getting the first stranded crew back alive. Chinese space officials organized a rapid turnaround launch of a replacement Shenzhou, accelerating preparations that would normally unfold over a longer period. The new spacecraft docked with Tiangong and allowed the three astronauts whose capsule had been damaged by debris to transfer into a fully functional vehicle. After final checks, they undocked and began their return journey, eventually landing back on Earth in what was described as a nominal touchdown, with all three taikonauts in stable condition after their extended stay in orbit, a recovery that was confirmed when the astronauts returned to Earth.

That successful rescue was widely seen as a validation of China’s ability to manage complex crewed operations, including contingency planning for damaged hardware. Yet the decision to use the next scheduled Shenzhou as a rescue craft meant the program had to accept a gap in its normal rotation scheme. Instead of overlapping missions with two docked crew vehicles, Tiangong would host a new crew with only one certified capsule available and no immediate backup. The relief of seeing the first trio walk away from their landing site was tempered by the knowledge that the system had burned through its margin for error, a reality underscored when three astronauts were later described as being stranded on the station after the rescue.

Three taikonauts in orbit without a safe ride home

The current crew’s situation is more subtle than a dramatic emergency, but in some ways more unsettling. The three astronauts aboard Tiangong are not in immediate danger; life support systems are functioning, the station is stable, and ground teams remain in constant contact. What makes their position precarious is that the Shenzhou spacecraft attached to the station is no longer considered a fully reliable reentry vehicle. After the earlier debris strike and the subsequent reshuffling of hardware, engineers have identified concerns with the capsule’s ability to withstand the stresses of a high-speed descent, leaving the crew effectively stuck until a new, fully vetted spacecraft can be launched, a predicament that has been described as three astronauts being stuck on China’s space station without a safe ride home.

From my perspective, what stands out is how quickly a modern space station can go from routine operations to a logistical puzzle. Tiangong was designed to host rotating crews with overlapping missions, but the combination of debris damage and finite spacecraft production has left the current occupants in a holding pattern. They can continue experiments, maintain the station and even conduct spacewalks if needed, yet every task is now colored by the knowledge that their path back to Earth depends on a future launch that has to arrive on time and in perfect working order. That tension is captured in reports that the three taikonauts are safe for now but still stranded, a phrase that neatly sums up the uneasy balance between normalcy and risk.

Space junk turns from background hazard to central character

At the heart of this story is not a faulty rocket or a miscalculated trajectory, but a piece of space junk that slammed into a critical spacecraft. For years, orbital debris has been treated as a kind of background hazard—something engineers model and track, but rarely the main character in a mission narrative. In this case, a fragment of human-made clutter in low-Earth orbit struck the Shenzhou return capsule with enough force to damage its thermal protection and other systems, forcing mission controllers to abandon plans for a normal reentry. Analysts have pointed out that this incident is a stark example of how debris can directly threaten crewed missions, not just satellites, a risk highlighted in assessments of how China’s stranded astronauts show the dangers of space junk.

When I look at the broader context, the Tiangong incident fits into a worrying trend. Low-Earth orbit is increasingly crowded with defunct satellites, spent rocket stages and fragments from past collisions and anti-satellite tests. Each new piece of debris raises the odds of another impact, creating a feedback loop that can generate even more fragments. The fact that a single strike could disable a crew’s only way home underscores how vulnerable current spacecraft designs remain to high-speed impacts. It also raises uncomfortable questions about how quickly the international community is moving to mitigate debris, especially when the same orbital shells are used by the International Space Station, commercial constellations and national laboratories alike.

Health, morale and life aboard a station you can’t yet leave

Despite the gravity of their situation, the three taikonauts on Tiangong are reported to be in good physical condition. Medical checks conducted from the ground and through onboard diagnostics indicate that their vital signs, bone density and muscle strength remain within expected ranges for a long-duration mission. They have access to exercise equipment, medical supplies and a steady flow of communications with mission control, all of which help maintain their health and morale. Officials have emphasized that the crew is stable and continuing their work, even as engineers on the ground focus on securing a safe return plan, a status reflected in updates that China’s stranded astronauts are in good condition after the space debris incident.

From a psychological standpoint, though, I can only imagine how different this mission must feel compared with a normal rotation. Astronauts train to accept risk, but they also train with the expectation that their spacecraft has been thoroughly tested for the ride home. Knowing that the attached capsule is no longer considered fully safe introduces a layer of uncertainty that can weigh on even the most disciplined crew. So far, reports suggest that the taikonauts are handling the situation with professionalism, continuing experiments and maintenance tasks as planned. Yet every routine day on Tiangong now doubles as an exercise in patience, as they wait for the next Shenzhou to be readied and launched to restore their ticket back to Earth.

How China and the world are responding to the new reality

On the ground, Chinese space officials are working to accelerate the production and launch schedule of a replacement Shenzhou that can serve as a fresh lifeboat for the current crew. That effort involves not just building hardware, but also re-evaluating inspection protocols, debris tracking and contingency plans for future missions. The incident has prompted a broader review of how Tiangong operations are structured, including whether to maintain two docked crew vehicles whenever possible and how to ensure that a damaged capsule can be quickly replaced. Analysts following the program have noted that the latest mission has effectively become a test case for how China manages long-duration station operations under stress, with three astronauts now stranded again after their ride home was struck by space junk.

Internationally, the Tiangong episode is feeding into a larger conversation about space safety and cooperation. Agencies that operate crewed vehicles in similar orbits are watching closely, not only out of concern for the taikonauts but also to draw lessons for their own programs. The incident reinforces calls for more aggressive debris mitigation, better sharing of tracking data and perhaps new design standards for crewed capsules that can better withstand small impacts. It also highlights the limits of national self-reliance in orbit: when a single country’s station faces a crisis, the ripple effects touch everyone who uses the same orbital highways. In that sense, the three stranded Chinese astronauts are not just a national story, but a global warning about the shared risks of an increasingly congested space environment.

What the Tiangong crisis reveals about the future of human spaceflight

For me, the most striking lesson from this saga is how thin the margin can be between routine success and crisis in human spaceflight. Tiangong, like the International Space Station before it, was built on the assumption that reliable crew vehicles would always be available to rotate astronauts and provide emergency escape options. The debris strike that damaged a Shenzhou capsule, and the subsequent decision to use another spacecraft as a rescue vehicle, exposed how quickly that assumption can be tested. With three more astronauts now effectively stuck until a new capsule arrives, the episode underscores that redundancy is not a luxury in orbit—it is a necessity, especially as more nations and private companies send people into space.

The situation has also unfolded in public view, with official briefings supplemented by analysis, animations and commentary shared widely online. One widely circulated explainer video broke down how the debris impact occurred and why it forced such drastic changes to the mission plan, helping viewers visualize the orbital mechanics and the vulnerabilities of the Shenzhou design; that kind of coverage, including detailed breakdowns in video explainers of the stranded mission, has turned a technical incident into a broader civics lesson about space safety. As the three taikonauts continue their work aboard Tiangong, their experience is likely to shape how engineers design future stations, how policymakers regulate orbital traffic and how the public understands the risks that come with pushing human presence deeper into the space around our planet.

More from MorningOverview