Underwater wind turbines, more accurately described as tidal and ocean current devices, are quietly reshaping the seafloor. They are not only feeding predictable clean power into coastal grids, they are also altering marine habitats, challenging long‑held ecological fears, and forcing regulators to rethink how energy and conservation fit together offshore.

As developers move from experimental pilots to commercial arrays, these submerged machines are starting to function as infrastructure for entire underwater neighborhoods. I see a technology that began as a climate tool now doubling as coastal protection, biodiversity support, and a test case for how to build in the ocean without simply taking from it.

From wind farms to underwater cities

For years, offshore wind farms have shown that energy structures can become de facto marine sanctuaries, with turbine foundations acting as hard substrate where little existed before. Studies of offshore projects report that these installations can boost local biodiversity by creating vertical reefs that attract shellfish, crustaceans, and fish, a pattern highlighted in early work on offshore biodiversity. As turbines go underwater, the same principle applies, but now the entire device, from base to blades, sits inside the water column where marine life can colonize every surface.

Observers who have dived around these structures describe something closer to a vertical village than a bare piece of engineering. One widely shared account of offshore turbines describes layers of life, from shellfish clinging to the base to larger predators hunting in the shadows of the tower. Underwater turbines extend that effect into deeper, darker waters, where natural hard habitat is often scarce and any new structure can become a focal point for entire food webs.

How tidal turbines actually work

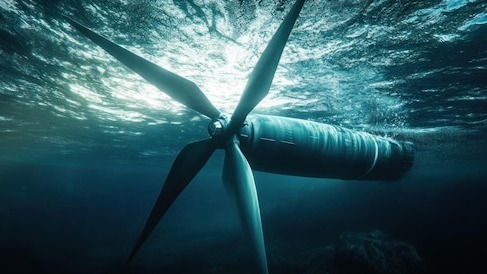

Technically, these machines are closer cousins to hydropower than to the spinning towers on a ridgeline. Tidal devices tap the kinetic energy of predictable ocean currents, converting the steady push of water into electricity through rotors that resemble slow‑moving propellers. Analysts describe tidal energy as a dependable and clean power source, precisely because the timing and strength of tides can be forecast decades in advance, unlike wind gusts or passing clouds.

Developers are now pushing that concept into stronger ocean currents that flow like underwater rivers. A Brazilian startup profiled in a report on Next generation devices argues that when the energy source is predictable and constant, this technology can offer genuine energy security for coastal communities. In Norway, a project highlighted in a social media post describes how the country built underwater turbines that harness power from ocean currents, turning a local physical feature into a long‑term power plant.

Artificial reefs, by design and by accident

Once a turbine is anchored to the seabed, it immediately begins to act as an artificial reef. Marine ecologists use that term to describe man‑made structures that mimic the ecological role of natural reefs, providing hard surfaces, crevices, and current breaks where organisms can settle and feed. A detailed review of the artificial reef effect notes that scour protections and foundations around offshore energy projects can generate enhanced habitat and productivity, essentially turning erosion control into a biodiversity feature.

Monitoring around early offshore wind projects has already documented this pattern. Surveys cited in work on Artificial reefs for ocean wildlife describe how turbine bases quickly accumulate mussels and barnacles, which in turn attract fish and then larger predators. Underwater turbines, which sit fully submerged, can amplify that effect by offering three‑dimensional habitat from seabed to mid‑water, especially in areas where trawling is restricted around the devices for safety reasons, giving marine life a de facto refuge from fishing pressure.

Misplaced fears and real trade‑offs

Critics have long warned that putting spinning blades in the sea could disrupt migration routes, injure marine mammals, or alter sediment flows in ways that harm coastal ecosystems. A comprehensive review of tidal projects, summarized in a paper on Misplaced fears?, acknowledges those concerns but finds that many predicted impacts have not materialized at the scale once feared. The authors describe tidal energy as a dependable and clean power source that stands as a compelling alternative to fossil fuels, and they argue that while local changes do occur, they are often smaller than the systemic risks posed by continued carbon emissions.

Researchers at Imperial College London have gone further, arguing that some of the ecological changes around tidal infrastructure can actually support climate resilience. In a study on New evidence, they report that changes do occur around tidal barrages and turbines, but most are not necessarily negative and can play a dual role in climate resilience. A companion summary on Reassessing the impacts stresses that the key is careful site selection and adaptive management, rather than assuming that any intervention offshore is inherently harmful.

When energy infrastructure becomes habitat policy

Once turbines start functioning as reefs, they blur the line between energy infrastructure and marine conservation. A detailed analysis of offshore structures notes that the reef effect can increase local productivity, but it also raises questions about whether we are creating ecological traps that attract fish into areas where they might later face new risks. That is why monitoring programs around offshore wind farms, described in work on offshore wildlife, recommend tracking ecological changes from the earliest stages of development.

Regulators are also weighing how underwater turbines fit into broader marine spatial planning. A study on offshore siting notes that, More importantly, installing wind turbines in the ocean can protect the environment and save land resources, while also avoiding some of the visual and noise impacts that onshore projects face. As underwater devices proliferate, I expect coastal governments to start treating them not just as power plants, but as long‑term habitat features that must be integrated with fisheries management, shipping lanes, and protected areas.

More from Morning Overview