Within just a few years, the idea of booking a room in orbit may shift from science fiction to a line item on a luxury travel itinerary. A private project called Voyager Station is being promoted as the world’s first space hotel, with backers targeting 2027 for its debut as a rotating resort circling Earth. If that schedule holds, the first generation of space tourists will trade ocean views for a constant panorama of the planet itself.

The concept is audacious: a vast wheel in low Earth orbit, spinning to create artificial gravity and outfitted with suites, restaurants, and recreation spaces. It is also arriving in a crowded moment for commercial spaceflight, where ambitious timelines often collide with engineering reality and funding constraints. The race to open this orbital hotel is as much a test of business models and public appetite as it is of rockets and life-support systems.

How Voyager Station became the flagship “space hotel” concept

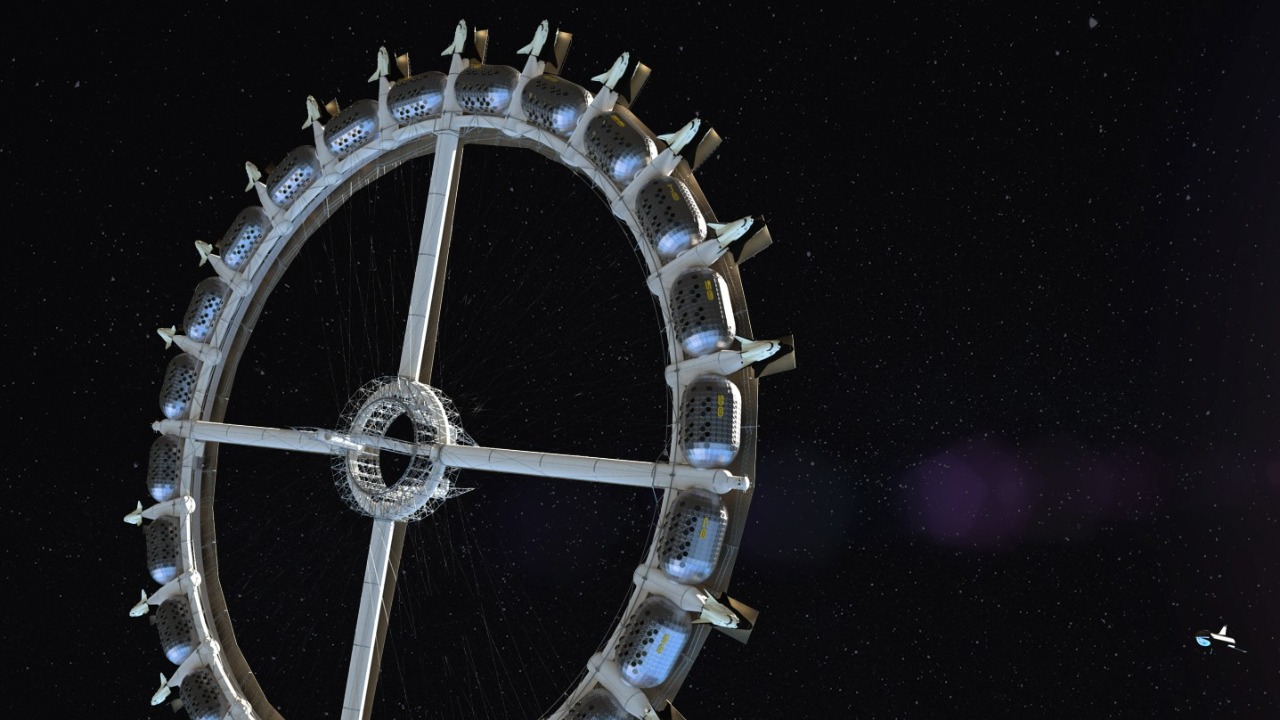

The centerpiece of the 2027 vision is Voyager Station, a planned ring-shaped structure designed to function as a cruise ship in orbit. The project has been described as a rotating space hotel that will use its spin to generate artificial gravity, allowing guests to walk, sleep, and eat in a way that feels closer to life on Earth than the weightlessness seen on the International Space Station. Early descriptions frame Voyager Station as a hybrid of a luxury resort and a research outpost, with private suites, shared lounges, and dedicated crew quarters arranged around its circular frame.

Supporters of the project have consistently presented Voyager Station as the first true orbital hotel, a facility built from the ground up for paying guests rather than retrofitted from a government lab. Reporting on the concept highlights that the station is intended to open by 2027 and that its rotating design is central to the promise of artificial gravity for visitors. That same framing appears in broader coverage of how vacationing in space could soon become a reality, with Voyager Station positioned as the most fully formed hotel proposal rather than a vague long-term dream.

The company behind the wheel: Orbital Assembly and Above Space

Behind the glossy renderings is a corporate story that has evolved alongside the project. Voyager Station was initially associated with the Gateway Foundation and later with Orbital Assembly Corporation, a company focused on building large rotating structures in orbit. More recently, Orbital Assembly Corporation has been described as operating under the name Above Space, signaling a rebranding that aligns the company more closely with its long-term goal of operating multiple orbital facilities rather than a single flagship station.

One key milestone for the team was entering into an Umbrella Space Act Agreement with NASA, a framework that allows collaboration on technical and operational issues without guaranteeing funding. Under that umbrella, the company has outlined a vision in which Voyager Station would eventually host up to 400 guests supported by a dedicated crew of 150 members, numbers that underscore the scale of the undertaking. The shift from Orbital Assembly Corporation to Above Space reflects an attempt to present the project as part of a broader ecosystem of orbital infrastructure rather than a one-off stunt.

Designing a rotating resort with artificial gravity

The most distinctive feature of Voyager Station is its rotating architecture, which is meant to create a gentle pull that mimics gravity along the outer ring. Instead of floating freely, guests would feel a downward force as the station spins, making everyday activities like showering, sleeping, and using the restroom far more practical than in microgravity. The design borrows heavily from classic space habitat concepts, but it packages them in a way that is explicitly tailored to tourism, with modules arranged like hotel wings around a central hub.

Architectural descriptions of the project emphasize that the station is planned as a large circular structure with an activity and gym module, restaurants, and other amenities distributed around the ring so that visitors can watch Earth slowly rotate past the windows as the station circles the planet. The team has said that they are planning on full operations by the end of the decade and that the overall layout is inspired by the cruise ship industry, with standardized modules that can be added or upgraded over time. Detailed coverage of the design notes that Voyager Station was originally planned with this modular, cruise-like architecture in mind, a choice that could make it easier to phase construction and adapt to changing demand.

What a stay in orbit is supposed to feel like

For all the engineering complexity, the pitch to future guests is surprisingly familiar: a high-end vacation with a dramatic view. Promotional material describes suites with large windows looking out over Earth, communal bars and restaurants, and recreation spaces where visitors can enjoy both the novelty of low gravity and the comfort of more Earth-like conditions in different parts of the station. The idea is to make space travel feel less like an expedition and more like a premium getaway, with curated experiences and attentive service.

Reporting on the project has sketched out what travelers can expect aboard Voyager Station, from the check-in process in orbit to the daily rhythm of meals, exercise, and sightseeing. One overview of how vacationing in space will become a reality explains that the station is being marketed as the world’s first space hotel set to launch in 2027 and that the experience is meant to blend adventure with a level of comfort that early astronauts could not have imagined. That same coverage notes that the era of space tourism is on the horizon and that guests will be able to enjoy a range of activities and amenities aboard Voyager Station, positioning the hotel as a kind of orbital resort rather than a spartan lab.

The business case: who pays for a room in space

Turning Voyager Station from a concept into a functioning hotel depends on more than rockets and robotics; it hinges on whether enough people are willing and able to pay for the experience. Early estimates suggest that a trip could cost around 5 million dollars per person, a figure that places it firmly in the realm of ultra-luxury travel. At that price point, the initial customer base is likely to be a mix of wealthy adventurers, corporate clients, and perhaps government or research teams renting space for specific projects.

Coverage of the project has noted that construction on the first-ever space hotel is expected to begin in 2026, with Voyager Station set to open the following year if all goes according to plan. The same reporting indicates that a stay will cost around 5 million dollars, underscoring how exclusive the first wave of orbital tourism will be. Those details appear in an analysis of how construction on Voyager Station is expected to unfold, and they highlight the financial tightrope the project must walk: prices must be high enough to cover enormous costs, yet not so high that the market evaporates.

Lessons from earlier space hotel dreams

Voyager Station is not the first attempt to sell the public on orbital hospitality, and the fate of earlier ventures offers a cautionary backdrop. Orion Span, an aerospace startup based in Silicon Valley, Californ, once promoted a project called Aurora Station as a compact luxury hotel in low Earth orbit. The company pitched short stays for private travelers and researchers, promising a rapid path from concept to launch that ultimately did not materialize as advertised.

Recent updates on that earlier effort describe how Orion Span and its Aurora Station concept failed to reach orbit, even as interest in commercial spaceflight continued to grow. Those retrospectives also point out that the Voyager Station, developed by the team now operating as Above Space, is designed as a much larger rotating facility capable of simulating gravity for its guests, a technical leap that sets it apart from Aurora Station’s smaller, microgravity-focused design. The comparison is explicit in analyses of Orion Span and Aurora Station, which frame Voyager Station as a successor that has learned from the missteps of earlier startups while still facing many of the same financial and regulatory hurdles.

Skepticism from the space community

Ambitious renderings and confident timelines have not silenced doubts among engineers, space enthusiasts, and industry observers. Critics point out that building a large rotating station in orbit is a complex and expensive undertaking that has never been attempted at this scale, and that the companies behind Voyager Station have yet to demonstrate hardware that matches their marketing. The gap between concept art and flight-ready modules remains a central concern for those who follow commercial space projects closely.

That skepticism is visible in community discussions where users compare Voyager Station to other private space station efforts. One widely shared thread notes that the team behind the hotel has built zero hardware so far, while companies like Axiom and Vast already have hardware in development and more concrete timelines for their own stations. Commenters urge readers to look at Axiom and Vast for real attempts to build orbital platforms, arguing that the hotel concept may be more aspirational than imminent. That contrast between flashy tourism pitches and quieter, hardware-first programs is shaping how the broader space community judges the 2027 target.

Marketing a “Starship culture” vacation

Even as engineers wrestle with feasibility, the language used to sell the project is aimed squarely at mainstream travelers. Advocates talk about a future in which going to space is just another option people pick for their vacation, akin to choosing between a cruise and a trip to a theme park. The idea is to normalize orbital travel as a lifestyle choice rather than a once-in-a-generation expedition, a shift that would dramatically expand the potential customer base if prices ever come down.

Some of the most vivid marketing language compares a trip to Voyager Station to a family outing, suggesting that a journey to orbit could one day feel as routine as a trip to Disneyland. Promoters have even invoked the idea of a “Starship culture,” arguing that there is a growing demand for experiences that blend science fiction aesthetics with real-world travel. That framing appears in coverage of how the project’s backers describe a “Starship culture” and demand for orbital vacations, language that reveals as much about the branding strategy as it does about the underlying technology.

Timelines, hype, and the 2027 question

The 2027 target has become a focal point for both excitement and scrutiny. On one hand, setting a specific year creates urgency and helps attract investors, partners, and early customers who want to be part of a historic first. On the other, the history of space projects is littered with delayed launches and revised schedules, especially when private companies attempt something that has never been done before. The gap between announcing a date and actually reaching orbit is where many grand visions falter.

Multiple reports have repeated that a rotating space hotel called Voyager Station is planned to open by 2027, often presenting that year as a key takeaway for readers trying to gauge how close space tourism really is. One detailed overview of the project lists the 2027 opening as a central point in its key takeaways, alongside the role of artificial gravity in making the hotel viable. Another analysis of the world’s first space hotel scheduled to open in 2027 underscores that the countdown to commercial orbital vacations is coming fast, quoting project leaders who insist that the timeline is achievable. That sense of momentum is captured in coverage of the world’s first space hotel scheduled to open, even as the underlying challenges remain formidable.

From concept art to construction: what has to happen next

For Voyager Station to move from renderings to reality, several major milestones must line up in quick succession. Launch providers will need to offer reliable, relatively affordable heavy-lift rockets capable of ferrying large station modules into orbit. The hotel team must finalize designs, secure manufacturing partners, and demonstrate key technologies like docking systems, life support, and the mechanisms that will control the station’s rotation. Each of these steps carries technical risk and requires substantial capital, especially for a structure that aims to host hundreds of people.

Industry observers note that construction on the first-ever space hotel is expected to begin in 2026, a schedule that leaves little room for delays if the 2027 opening is to be met. That timeline assumes that design work, regulatory approvals, and funding are all in place in time to start building and testing modules on the ground before launching them. The same reports that outline how construction on the first-ever space hotel will unfold also highlight the scale of the challenge, noting that even government-backed stations have taken years to assemble and commission. For Voyager Station, the path from here to 2027 will be a test of whether private space infrastructure can move at startup speed while still meeting the unforgiving demands of orbital engineering.

More from MorningOverview