Gov. Kathy Hochul and Rep. Mikie Sherrill are selling nuclear power as the silver bullet that can decarbonize their states while keeping the lights on and bills in check. Their rhetoric is bold, but the policies underneath it leave a gaping practical and political hole that neither has convincingly addressed. The scale, timing, and cost of what they are promising simply do not line up with the realities of the grid, the market, or their own climate laws.

New York and New Jersey do need firm, low carbon power, especially as they push buildings and cars off fossil fuels. Yet the way Hochul and Sherrill are leaning on nuclear, without squaring the tradeoffs on rates, siting, and backup power, risks deepening affordability problems and reliability threats rather than solving them.

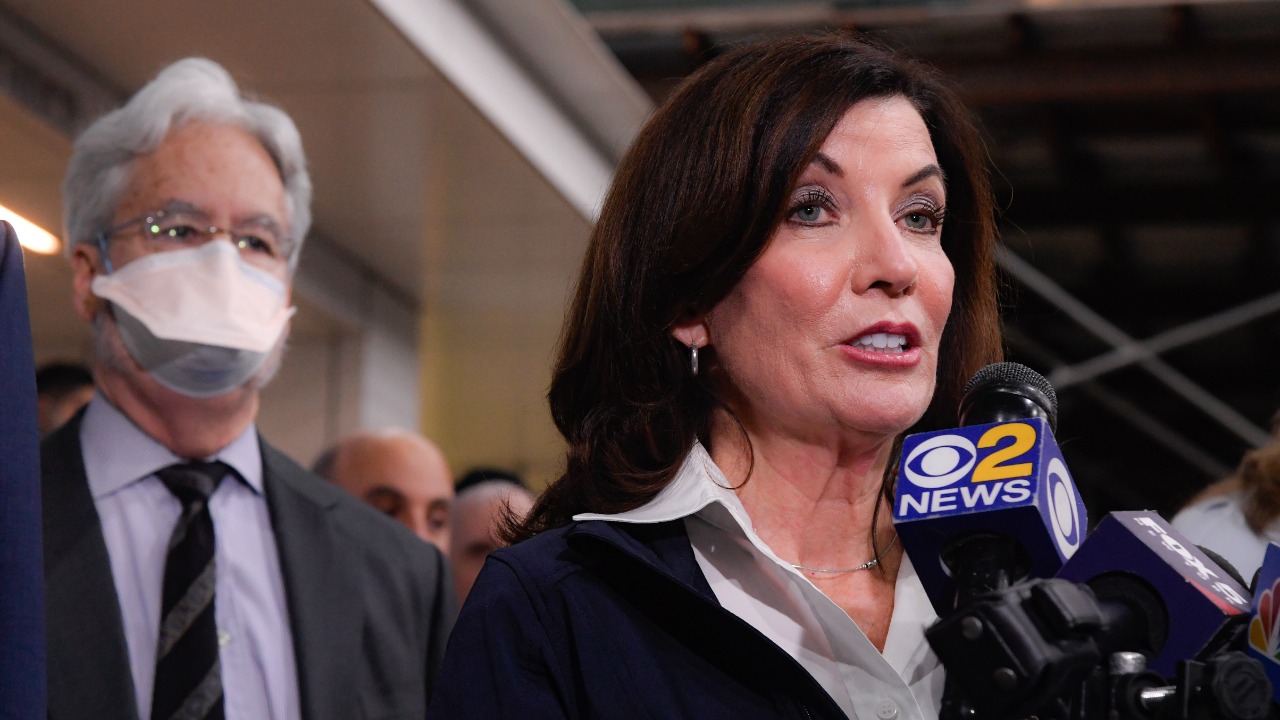

Hochul’s nuclear upgrade collides with her own record

Kathy Hochul has tried to recast herself as a nuclear champion, telling New Yorkers that atomic energy is now a “vital part” of an all of the above clean power strategy. She has highlighted that last summer she took what she called a bold step by greenlighting the first nuclear power project in a generation, presenting it as a cornerstone of building the state’s clean energy future together, a move she later reinforced when she upgraded her vision for nuclear in New York. She has since gone further, with New York Gov. Kathy Hochul calling for the state to pursue up to 5,000 megawatts of new nuclear energy, a target that would require a fleet of new reactors and a massive build out of transmission and support infrastructure, as described in her push for 5,000 megawatts of capacity.

Yet Hochul’s nuclear pivot sits uneasily beside New York’s recent history. Her predecessor Andrew Cuomo used state power to force the closure of the Indian Point nuclear plant, which had supplied about a fourth of New York City’s electricity, a decision that left the downstate grid more dependent on gas and raised concerns about what it may cost New Yorkers, a tradeoff laid bare in the account of how Andrew Cuomo closed. Now Hochul is asking residents to trust a new wave of reactors after years of policy that pushed nuclear off the system, a reversal that fuels skepticism among both climate advocates and ratepayers who are already worried about energy affordability.

Big promises, slow timelines, and rising subsidies

The core problem is timing. Hochul’s climate laws demand rapid cuts in emissions, but new nuclear plants are slow to plan, license, and build, often taking close to a decade from concept to operation. Analysts like Jonathan Lesser have argued that the engineering, economic, and political challenge of delivering enough reactors in time to meet near term climate targets is enormous, warning that Kathy Hochul and Mikie Sherrill are “dreaming” if they think nuclear alone can solve their energy woes or address New Jersey’s challenges quickly, a critique captured in the analysis of Jonathan Lesser. Even Hochul’s own nuclear initiative is framed as a long term bet, with state officials acknowledging that the process of identifying sites, securing permits, and lining up financing will stretch well beyond the current decade.

In the meantime, New York is doubling down on subsidies to keep existing reactors running. The state’s utility regulator has extended support for Constellation’s Nine Mile Point nuclear plant in Oswego, New York, and other facilities, locking in payments that are expected to last until midcentury while policymakers simultaneously talk about adding gigawatts of new nuclear energy, a commitment detailed in the decision to extend nuclear subsidies. That means ratepayers are already paying to preserve today’s fleet while being asked to underwrite tomorrow’s, even though the new reactors will not arrive in time to relieve near term reliability crunches or to offset the cost of aggressive electrification mandates.

Political backlash from both greens and bill payers

Hochul’s nuclear turn has not united her climate coalition. Over the summer, reporting on her nuclear power plant initiative noted that Kathy Hochul’s nuclear vision faces big questions and bottlenecks, including fierce resistance from environmental groups that had spent years campaigning for a grid dominated by renewables, a tension laid out in the examination of how Hochul’s nuclear vision is colliding with existing climate plans. One of the most vocal critics, NY Renews, the progressive pro renewables group with which Zohran Mamdani campaigned last year, came out against the expansion or full scale development of new nuclear plants, arguing that the state should instead clear the way for more electricity generation from wind and solar, a stance described in the account of how NY Renews and opposed the plan.

Grassroots environmentalists have echoed those concerns, warning that new reactors could crowd out investment in renewables and saddle communities with long term waste and safety risks. Hochul herself has acknowledged that some will oppose the move, conceding that there are already critics of nuclear power who want the state to focus on cutting demand and expanding clean electricity from wind and solar generation, a dynamic captured in coverage of how environmentalists are not. At the same time, few climate advocates are in the mood to give Hochul the benefit of the doubt after her repeated backtracking on other clean energy policies, including support for solar, wind, and batteries, a frustration described in reporting that noted how few climate advocates trust her new nuclear push.

Sherrill’s New Jersey gamble on rates and reliability

Across the Hudson, Mikie Sherrill is walking into a similar trap. New Jersey lawmakers are considering a proposal to build a nuclear plant that would increase utility rates, with estimates varying widely on how much, and the debate is unfolding just as Sherrill prepares to take office under a framework set by an outgoing administration, a situation described in the analysis of how a nuclear bill could. Sherrill has embraced nuclear as part of a broader clean energy strategy, but she has not yet explained how households already straining under high bills will absorb another round of increases tied to a single, capital intensive project that may not deliver power for years.

Critics like Jonathan Lesser argue that both Hochul and Sherrill are leaning on nuclear as a political shield while ignoring the near term reliability risks created by their own policies. In his assessment of their plans, Lesser warns that if Hochul and Sherrill continue relying on more wind and solar, along with high cost battery storage, the sure result will be blackouts and soaring electricity prices, a warning he delivers in his role with the National Center for Energy Analytics and that is summarized in the discussion of what happens Hochul and Sherrill on their current path. He also notes that during extreme weather, such as an expected snowpocalypse, wind and solar output can plunge just as demand spikes, leaving grids exposed if firm capacity is not in place, a vulnerability highlighted in the account that begins, “As for more wind and solar power reliability,” which describes how during the snowpocalypse renewables may underperform.

More from Morning Overview