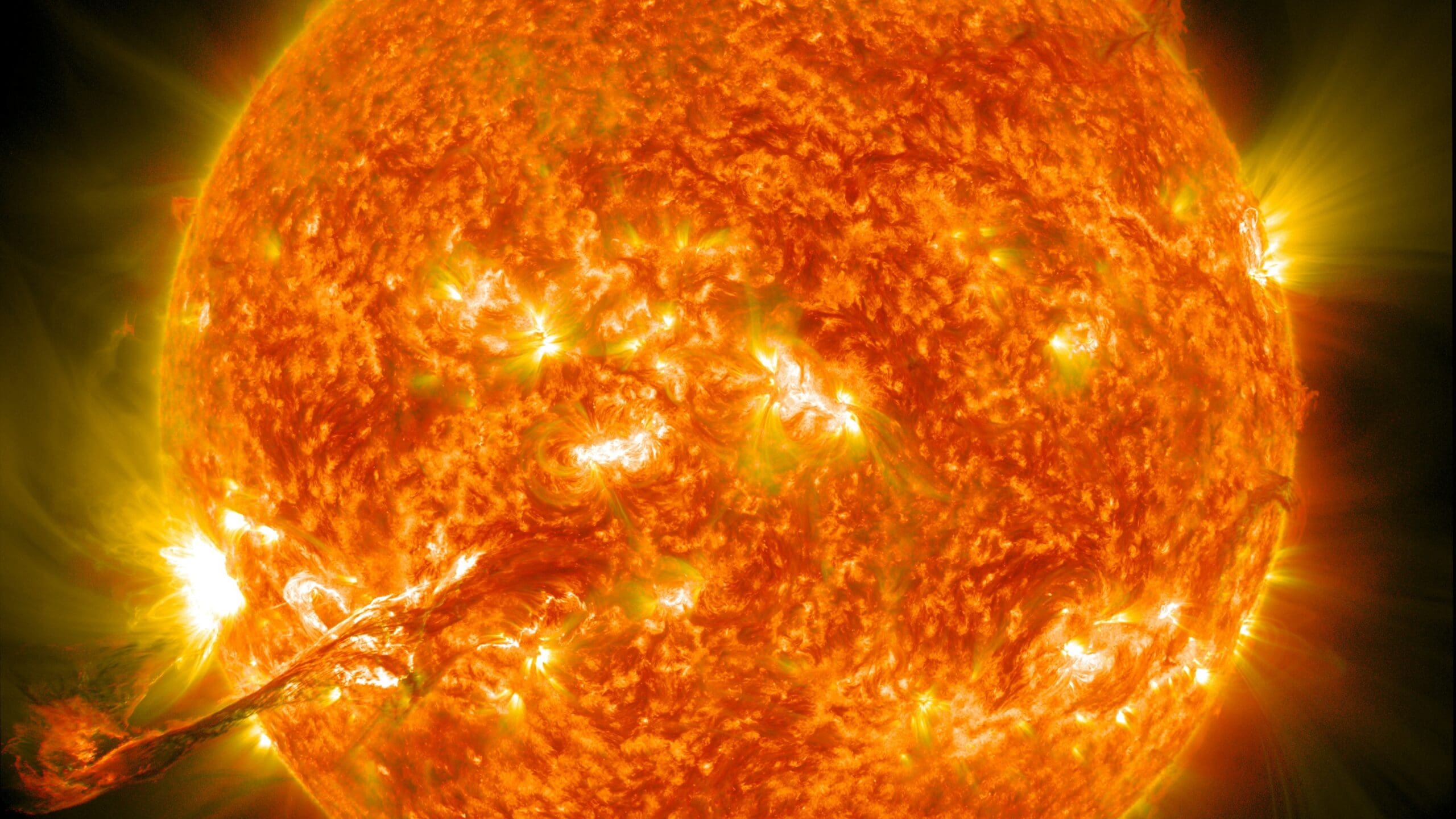

The Sun has snapped into a hyperactive mood, unleashing a rapid-fire sequence of powerful eruptions just as a volatile sunspot rotates into direct view of Earth. The result is a wild solar flare barrage that is already rattling Earth’s upper atmosphere and setting the stage for more space weather in the days ahead. As the giant active region swings fully into geoeffective position, the question is no longer whether it is erupting, but how those blasts will intersect with our planet’s magnetic shield.

At the heart of the drama is a complex sunspot cluster that has already produced one of the strongest flares of Solar Cycle 25 and dozens of smaller bursts in barely a day. I am watching a textbook example of how a single unstable region can dominate the Sun’s output, with each new flare raising the odds of radio blackouts, navigation glitches, and, if the geometry lines up, spectacular auroras far from the polar circles.

The monster sunspot that flipped the switch

The current surge in activity traces back to a sprawling active region cataloged as sunspot 4366, which has grown into a magnetic tangle large enough to be seen without magnification at sunset through proper solar filters. Earlier this week, that region rotated onto the visible disk and almost immediately began firing, with observers describing a Sunspot area that looked primed for trouble. Its emergence coincided with a sharp uptick in X‑class and M‑class flares, the two most energetic categories on the standard scale used by space weather forecasters.

Magnetogram data show that sunspot region 4366 has developed a Complex configuration with a Beta, Gamma, Delta magnetic layout, a notoriously unstable mix that often precedes major eruptions. In practical terms, that means opposite magnetic polarities are pressed tightly together, storing energy that can be released suddenly as flares. When such a region rotates from the Sun’s eastern limb toward the central meridian, as 4366 is doing now, any eruption is more likely to be directed toward Earth rather than off to the side.

Record-strength X8 flare and a 27-flare barrage

The most eye-catching blast so far has been an X‑class flare that ranks among the strongest of the current cycle, with measurements pegging it around X8.1 to X8.3. Solar monitors tracking the event reported that a Giant sunspot region EXPLODES with X8.1 flare, while video analysis of the same eruption highlighted a Sunpsot AR4366 that produced an X8.3‑class event on Feb. 1, 2026, captured in detail in a widely shared Sunpsot clip. That slight discrepancy in peak value reflects different instruments and processing, but both reports agree that this was the most powerful flare of Solar Cycle 25 so far.

Crucially, that monster outburst was not an isolated spike. Over roughly 24 hours, the same active region launched a staggering 27 solar flares, a pace that space physicists rarely see sustained from a single source. One analysis described a monster sunspot taking aim at Earth after firing off dozens of powerful flares on Sunday and Monday, including the massive X‑class explosion. That kind of relentless cadence is a hallmark of a region that is still evolving, which means the current barrage may not yet represent its peak.

Radio blackouts, CMEs and what hits Earth

Each major flare from sunspot 4366 has sent a pulse of X‑rays and extreme ultraviolet light racing toward Earth at the speed of light, compressing and ionizing the upper atmosphere on the dayside. One of the recent X‑class events produced a strong radio blackout that ionized Earth’s upper atmosphere enough to disrupt high‑frequency communications. Pilots, mariners, and amateur radio operators are among the first to notice when those shortwave bands suddenly go quiet during such storms.

Flares of this magnitude often coincide with coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, vast clouds of charged particles that can trigger geomagnetic storms if they collide with our planet’s magnetic field. Early assessments of the X8‑class eruption suggest that at least one CME blasted away from the Sun, but initial modeling indicated CME UPDATE notes of almost no interaction with Earth for that particular cloud. That is a reminder that even spectacular flares do not always translate into severe geomagnetic storms, because the direction and magnetic orientation of each CME matter as much as its raw power.

Aurora potential and how to track it

When a CME does connect, the payoff for skywatchers can be extraordinary. Earlier in the current solar cycle, a G5‑rated geomagnetic storm, the strongest category on the scale, lit up skies across the Northern Hemisphere with vivid auroras that reached well into the mid‑latitudes. Photos from that event showed curtains of green and red light as a rare solar storm swept Earth, and forecasters pointed to a NOAA aurora dashboard that predicts in real time how far south the lights might be visible in coming days. A separate gallery of images from that storm highlighted how a powerful sunspot cluster and its coronal mass ejection combined to produce a global light show.

Even during less extreme events, the northern lights can dip into the continental United States, with one recent forecast noting that auroras might be visible in 12 states on a single night and sharing a “Where can I see the northern lights” map courtesy of Where NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. For the current barrage, aurora hunters are already being urged to Check Forecasts and Keep an eye on updates from the Check Forecasts NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center for the latest odds. The same office maintains the main NOAA portal for alerts on geomagnetic storms, solar radiation, and radio blackouts.

Solar cycle context and what comes next

The ferocity of sunspot 4366 fits a broader pattern as Solar Cycle 25 approaches its expected maximum, a phase when large, magnetically complex regions become more common. Analysts tracking the current episode describe a volatile sunspot now facing Earth that has unleashed a rapid‑fire series of solar flares, and they note that such active regions are becoming more frequent as the cycle ramps up. One report framed it bluntly, saying the Earth facing sunspot has turned toward us and unleashed a stunning flare barrage, a sign that we are entering a more turbulent phase of solar weather.

Within that context, the X8‑class eruption and its companions look less like an anomaly and more like a preview of what the next couple of years may hold. Space weather specialists are already dissecting the sequence of events, from the initial M‑class bursts to the crescendo of X‑class flares, noting that an Update on Sunspot 4366 described a six‑hour‑long trio of M and X‑class flares before it outdid itself with the biggest blast. Another overview of recent activity summed it up by saying that Solar activity has surged into overdrive, with Sun news for February 1‑2 highlighting how Over the past 24 hours the same region kept firing again and again. As the Sun continues to turn that unstable region toward the center of the disk, I expect forecasters to stay on high alert for the next big flash.

More from Morning Overview