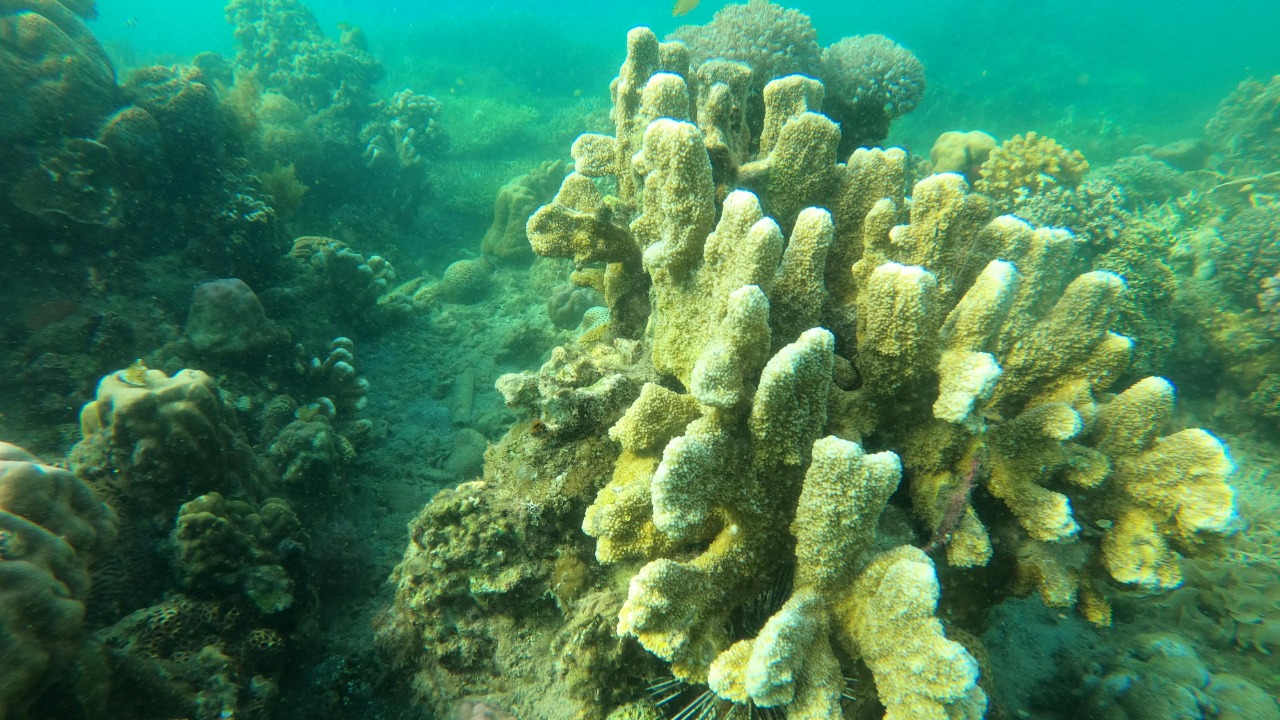

Long before a storm surge reaches Miami Beach or Fort Lauderdale, a different kind of seawall is already at work offshore. Florida’s coral reefs, battered by warming seas and disease, are still quietly knocking down waves and sparing coastal cities from millions of dollars in flood damage that would otherwise hit streets, homes, and high-rise towers. New research puts hard numbers on that protection and warns that if the reefs keep fading, the financial and human costs inland will climb fast.

Instead of concrete and steel, this defense system is built from living limestone ridges that rise from the seafloor. I see the emerging science as a blunt economic argument: keeping these reefs intact is not just about saving wildlife, it is about preserving a piece of infrastructure that coastal communities would struggle to replace at any price.

Reefs as Florida’s first line of flood defense

Florida’s Coral Reef stretches for hundreds of miles along the state’s southeast and Keys coastline, forming a natural breakwater that intercepts storm energy before it reaches shore. State managers describe how this living barrier underpins everything from water quality to tourism, with Florida agencies treating the reef tract as critical coastal infrastructure as well as habitat. When storms push in from the Atlantic, those same structures help decide whether waves lap at the dunes or pour into ground-floor lobbies.

Scientists have now quantified that role in stark terms, showing that continued degradation of Florida’s coral reefs could annually increase flooding to more than 8.7 square kilometers of coastal land. That figure translates into neighborhoods that would newly find themselves in the flood zone, along with the roads, power infrastructure, and businesses that keep metropolitan South Florida running.

What the new flood-risk science shows

The latest modeling work goes beyond broad warnings and drills into how much extra water would reach specific communities if the reef crest continues to erode. In a peer reviewed analysis of Data and Results, researchers examined “Coastal Flood Risk Increase From Coral Reef Degradation” along 430 km of the State of Florida shoreline. They found that as the reef surface lowers and roughness declines, storm-driven water levels rise higher and push farther inland, exposing more people and property to damage.

Federal scientists have echoed that warning in a separate assessment of fading coral reefs, which concluded that the loss of reef height and complexity would sharply increase coastal flood risk even before water ever reaches land-based seawalls. Together, these studies frame the reef not as a scenic backdrop but as a measurable control on how deep and how often streets in Miami-Dade and Broward counties will flood in future storms.

Millions in avoided damage, mapped down to the block

Where the new work becomes politically potent is in its accounting of avoided losses, the dollars that do not have to be spent on repairs because the reef is still there. A recent analysis highlighted by Jan researchers found that Florida reefs offer multimillion dollar flood protection each year, essentially acting as a free insurance policy for coastal real estate. One scientist put it bluntly, saying that “Coral reefs, if not stressed, can continue to provide this protection at a fraction of the potential cost” of engineered defenses.

That economic lens is sharpened further in local mapping that shows how water behaves with and without the reef. In Bal Harbour, a barrier island village lined with luxury condos and hotels, scientists produced graphics that reveal which parts of Bal Harbour are newly inundated when the reef is degraded. Coastal geologist Storlazzi described how the modeled surge “shows how it is punching further inland,” a phrase that captures the difference between a flooded parking garage and water lapping at elevator banks and electrical rooms.

How a “Healthy” reef blunts 97% of wave energy

The physical reason these economic benefits exist is straightforward: a rough, elevated reef forces incoming waves to break offshore, bleeding off energy that would otherwise slam into seawalls and streets. A federal status report on Shoreline Protection notes that Healthy coral reefs can absorb 97% of wave energy from storms and hurricanes, buffering shorelines and helping to prevent erosion and flooding. That figure is not a rounding error, it is the difference between a storm that scours away beaches and one that leaves them largely intact.

Florida’s own outreach materials on the Value of its Coral Reef emphasize that People benefit greatly from Florida’s Coral Reef, often without realizing it, because South Florida enjoys the coral sand beach and calm nearshore waters that the reef helps create. Those same conditions that draw tourists to snorkel and scuba dive also mean that storm waves arrive smaller and slower, giving dunes and mangroves a better chance to hold the line.

Restoration, equity, and the cost of letting reefs fail

As the science clarifies the stakes, the policy question becomes whether to treat reef conservation as a core part of flood management. A recent synthesis of work in Florida and Puerto Rico found that targeted More coral-reef restoration could save lives and property, with some of the highest benefits accruing to vulnerable inland communities and those living in poverty. In other words, the people who gain most from a functioning reef are not only beachfront homeowners but also residents farther inland who are less able to absorb flood losses.

Another assessment framed the stakes in simple budget terms, finding that Florida reefs offer multimillion dollar flood protection if they survive, a conditional that underscores how quickly those benefits could vanish. In coverage of the same work, Jan researchers stressed that while restoration and enhancement are desirable, the immediate priority is to “protect what we have” before further degradation locks in higher flood risk.

More from Morning Overview