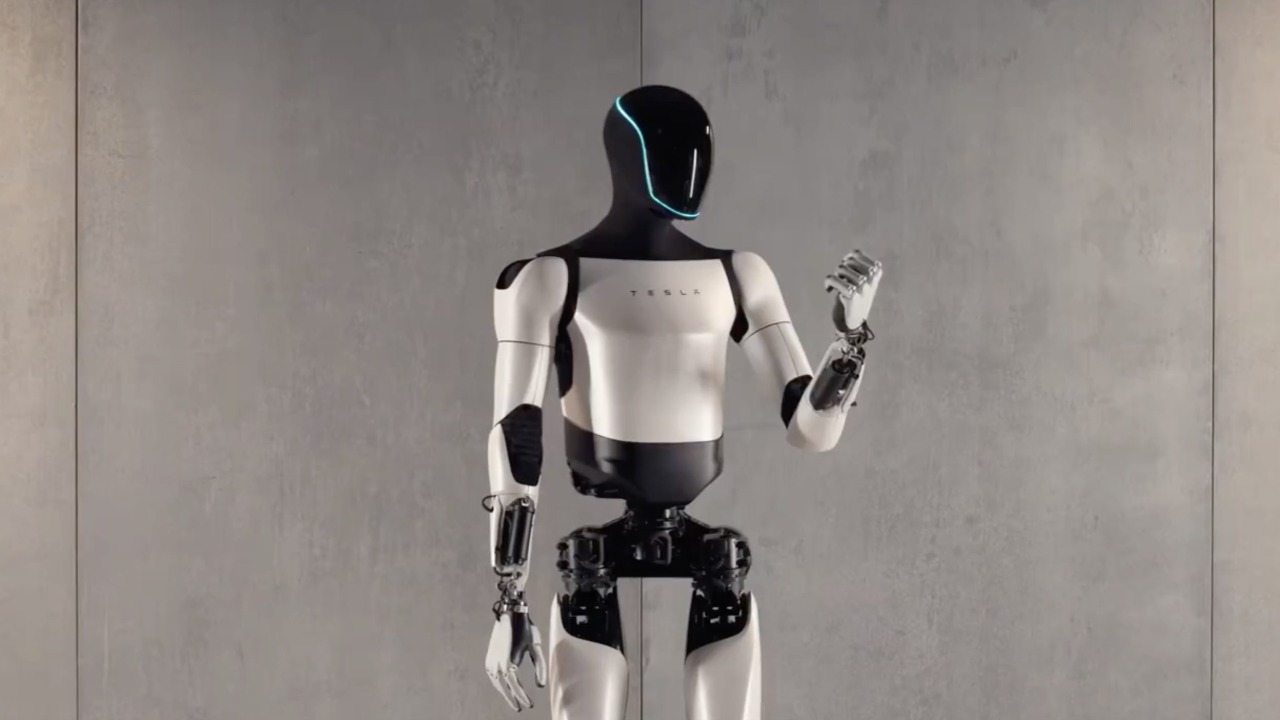

SpaceX is quietly reshaping its Mars strategy around a new kind of astronaut: a Tesla-built humanoid that can work where humans cannot yet safely live. The company wants Optimus, Tesla’s bipedal robot, to touch Martian soil before any crewed mission, turning a sci‑fi prop into the first settler of another world. That ambition is not a side project, it is emerging as a central pillar of Elon Musk’s long‑stated goal of building a city on Mars.

Musk’s new Mars pitch: send the robots first

Elon Musk has spent years talking about cities on Mars, but his latest pitch adds a crucial twist: the first “colonists” may be machines built in a Tesla factory rather than humans in spacesuits. In a recent SpaceX event, Musk outlined a plan in which Optimus, Tesla’s humanoid robot, would be shipped to Mar ahead of any crewed landing, effectively becoming the company’s pathfinder workforce. The idea is simple but radical, turning a consumer robotics project into the vanguard of interplanetary settlement and reframing Mars not as a place humans rush to occupy, but as a construction site that robots prepare in advance.

In that presentation, Musk described how Optimus would be integrated into upcoming Starship cargo flights, positioning the robot as a core part of SpaceX’s early surface operations rather than a later add‑on. The plan, highlighted in a video where Musk’s “secret” strategy for Optimus on Mar was teased, shows how tightly he is now linking Tesla’s robotics program to SpaceX’s exploration roadmap, with Musk, Optimus, Mar all framed as pieces of the same long‑term puzzle.

From factory floors to Martian regolith: what Optimus is built to do

On Earth, Optimus is being designed to take over repetitive, labor‑intensive tasks in Tesla’s own plants, but the same traits that make it useful on a factory floor also make it attractive for Mars. The robot is meant to lift, carry, and manipulate tools for extended periods, operating in environments that would be exhausting or dangerous for humans. That design philosophy, focused on physical endurance and task flexibility rather than flashy consumer features, aligns almost perfectly with what a remote, unpressurized Martian worksite demands.

Reporting on Musk’s Mars vision notes that Optimus is explicitly Designed for labor‑intensive tasks, with the Optimus robot pitched as a way to set up solar panels, shelters, and other infrastructure during the early, hazardous stages of settlement. In other words, the robot is being engineered not just as a novelty, but as a construction and maintenance worker that can operate in thin air, abrasive dust, and extreme temperature swings long before any human crew can safely spend months on the surface.

Why SpaceX wants Tesla’s robot on Mars before any human

SpaceX’s interest in sending Optimus ahead of astronauts is rooted in risk management as much as ambition. Early Mars missions will be unforgiving, with untested hardware, unknown local hazards, and no quick rescue options. By deploying a fleet of humanoid robots first, the company can test landing systems, power infrastructure, and surface operations without putting human lives on the line. Robots can fail, be repaired, or be replaced in ways that human crews simply cannot, turning the first wave of missions into a high‑stakes dress rehearsal rather than a one‑shot gamble.

New mission concepts described in recent coverage suggest that Tesla’s humanoid platform is being evaluated as a primary payload for early cargo flights, with planners openly discussing how Tesla Built a Robot and SpaceX Wants to Drop It on Mars First. The logic is straightforward: if Optimus can assemble solar farms, unpack habitats, and scout landing zones, then the first human crew can arrive to a partially prepared outpost instead of a bare patch of regolith, dramatically improving their odds of survival and mission success.

Starship as the delivery truck for a robot workforce

None of this is possible without a heavy‑lift system capable of throwing large, delicate cargo toward Mars, and that is where Starship comes in. SpaceX’s long‑term roadmap calls for a series of uncrewed Starship launches timed to favorable planetary alignments, each one packed with supplies, infrastructure, and now, potentially, humanoid robots. The company’s own planning documents describe how Five massive Starships would depart when Earth and Mars line up, creating a convoy of uncrewed vehicles that can deliver hundreds of tons of hardware to the Red Planet in a single campaign.

Analysts who have examined those plans note that these Five uncrewed Starships would lift off when Earth and Mars are aligned, and that the architecture explicitly links SpaceX’s launch system to Musk’s electric car company, Tesla. In practice, that means Starship is being treated as a giant delivery truck for Optimus units and Tesla‑branded power systems, turning each uncrewed mission into a bulk shipment of robots, batteries, and solar arrays that can be deployed autonomously on arrival.

Inside the “Mars city” vision that ties SpaceX, Tesla and Neuralink together

Musk’s Mars rhetoric has always been expansive, but his latest framing casts the Red Planet as a testbed for a full technology stack that spans rockets, cars, robots, and brain‑computer interfaces. In a widely watched update, he outlined a “Mars city” concept in which SpaceX provides transport, Tesla supplies energy and robotics, and Neuralink explores ways to keep human settlers healthy and functional in a hostile environment. The message is that Mars is not just a destination, it is a proving ground for the entire Musk ecosystem.

In that presentation, Musk spoke about Elon and Mars in the same breath as Neuralink, New Jersey regulatory fights, and Tesla’s broader business, underscoring how intertwined his ventures have become. The segment that detailed his new plan for a Mars city, captured in a video that walks through Jun, Elon, Mars, Neuralink, New Jersey, Tesla, makes clear that Optimus is expected to be a bridge between these worlds, a physical embodiment of Tesla’s AI and hardware that can operate inside a SpaceX mission profile and, eventually, support human crews whose own capabilities may be extended by Neuralink implants.

What the first Starship flights to Mars will actually carry

While the public often fixates on the first human landing, SpaceX’s near‑term Mars flights are being structured as cargo runs, and that is where Optimus fits in. Company plans described by Musk indicate that the earliest Starship missions to Mars will not have any astronauts on board at all. Instead, they will be packed with equipment, supplies, and robotic systems that can start building out the basic infrastructure needed for a later crewed presence, from power generation to communications and life‑support precursors.

One detailed account of this strategy notes that Aug planning documents explicitly state that While no humans would have a seat on the first flight to Mars, Starship will not be empty. Instead, the vehicle would carry cargo and robotic systems to prepare the way for people, with Musk suggesting that human landings could follow in the early 2030s if everything goes to plan. That description, captured in coverage of how Aug, While, Mars, Starship, Instead frame the first mission, aligns neatly with the idea of filling those early flights with Optimus units and the hardware they need to function autonomously on the surface.

Why a humanoid shape matters on a planet with no humans

At first glance, sending a human‑shaped robot to a world with no existing human infrastructure might seem like a strange choice. In practice, the humanoid form is a bet on compatibility with tools and environments that will be designed by and for people. If Musk expects future Martian habitats, vehicles, and workstations to be built around human ergonomics, then a bipedal robot with hands becomes a logical way to bridge the gap between fully autonomous machines and the eventual arrival of crews who will use the same doors, ladders, and control panels.

Mission concepts that discuss how Tesla Built a Robot and SpaceX Wants to Drop It on Mars First emphasize that the humanoid layout is not about making Optimus look like a person, it is about ensuring it can operate equipment that will later be shared with astronauts. In one widely shared clip, planners talk through how a Tesla Built Robot and SpaceX Wants to Drop It on Mars First so that the same airlocks, vehicles, and tools can be used seamlessly by both robots and humans, reducing the need to design two parallel systems for every task.

Mars as “life insurance” and the role of a tireless robot labor force

Musk often describes Mars as a form of “life insurance” for humanity, a backup location in case Earth suffers a catastrophe. That framing only makes sense if a self‑sustaining settlement can be built, and that is where a tireless robot labor force becomes more than a convenience. If Optimus can work around the clock to expand solar farms, bury habitat modules for radiation protection, and maintain critical systems, then the threshold for a viable outpost drops from thousands of human workers to a smaller crew supported by hundreds or thousands of machines.

Coverage of Musk’s Mars rationale spells this out explicitly, noting that Optimus is Designed for heavy, repetitive work and that the Optimus robot could be instrumental in setting up solar panels, shelters, and other infrastructure during the early, hazardous stages of settlement. By leaning on a robotic workforce to handle the most dangerous and monotonous jobs, SpaceX and Tesla can move closer to the kind of resilient, long‑term presence that a true planetary backup requires, rather than a short‑term flag‑planting mission that depends on constant resupply from Earth.

The strategic bet: integrating Tesla’s AI into SpaceX’s harshest mission

Underneath the spectacle of humanoid robots on Mars is a deeper strategic bet: that Tesla’s advances in AI, sensing, and actuation can be repurposed for one of the harshest environments in the solar system. Optimus is being trained to navigate cluttered factory floors, interpret human instructions, and manipulate complex objects, all skills that translate directly to a remote construction site on another planet. By deploying the robot on Mars, Musk is effectively using the Red Planet as a stress test for Tesla’s AI stack, with every successful task feeding back into better models and hardware on Earth.

That feedback loop runs both ways. As Optimus learns to operate in Tesla’s plants and, eventually, in more public settings, the company can refine its design for the specific challenges of Martian gravity, dust, and isolation. The decision to make SpaceX Wants to Wants Drop It on Mars First is not just a publicity move, it is a way to align the incentives of two companies so that every improvement in Tesla’s robotics directly advances SpaceX’s most ambitious mission profile.

More from MorningOverview