SpaceX is no longer content with using rockets to launch satellites that beam internet back to Earth. The company now wants to loft an entire layer of the AI economy into orbit, powered directly by the Sun rather than by terrestrial grids that are already straining under data center demand. The plan is audacious in scale and intent, turning space into a platform for computation, not just communication, and forcing regulators and rivals to rethink what an AI infrastructure race looks like.

At the heart of the proposal is a constellation of up to one million satellites that would function as solar-fed data centers, effectively orbital AI supercomputers. If SpaceX can make that vision real, it would not just extend its Starlink footprint, it would shift where and how the most power-hungry algorithms on the planet are run.

The one‑million satellite bet on orbital AI

The core of SpaceX’s new filing is a request to deploy as many as 1,000,000 satellites that act as a distributed “orbital data center” rather than a traditional communications network. In documents submitted to regulators, Elon Musk’s space exploration company describes a system in which each spacecraft carries high performance computing hardware, collectively forming a mesh of AI supercomputers in low Earth orbit that can be scaled far beyond what any single ground campus could host. The scale of that ambition, a million nodes in space, is explicitly framed as a step toward a Kardashev-style civilization that begins to tap the energy resources of its star, a point SpaceX highlights when it calls the project a first move toward becoming a Kardashe level society.

Regulatory filings show that Musk’s SpaceX has formally applied to launch this one million strong constellation into orbit, building on the company’s existing Starlink experience but with a very different purpose. Reports on the application note that Musk is positioning the system as a way to serve “billions of users globally” with AI services, not just connectivity, and that the company has told regulators the satellites will be optimized for computation rather than for consumer broadband alone. In a separate description of the same project, Jan and other commentators describe it as an “orbital data center” that would sit on top of the existing Starlink internet layer, effectively turning the sky into a cloud platform.

Solar power instead of Earth’s grids

SpaceX is explicit that the main constraint on AI growth is no longer just chips, it is electricity, and that is where the company believes orbit offers a structural advantage. In its request for approval, the firm argues that by directly harvesting near constant sunlight in space, its satellites can run AI workloads without drawing on terrestrial grids that are already under pressure from hyperscale data centers. The company claims that the orbital facilities will be a cheaper and more environmentally friendly alternative to land based centers, a point it makes repeatedly when describing the satellites as solar powered data hubs that can harness the Sun’s full power.

Earlier this year, Musk said publicly that solar space based AI data centres could be possible in two to three years, arguing that space based solar could power AI more efficiently than ground installations and hinting at a long term push toward large scale extraterrestrial energy infrastructure. That timeline, which he linked to the development of Space based solar arrays, aligns with the new filing’s suggestion that near constant solar exposure in orbit, combined with low operating and maintenance costs, could deliver transformative energy efficiency. In one description of the project, SpaceX states that “by directly harnessing near constant solar power with little operating or maintenance costs, these satellites will achieve transformative energy efficiency,” a claim repeated in financial filings that detail how the company expects to cut the cost per unit of computation by avoiding Earth’s grids and instead tapping near constant sunlight.

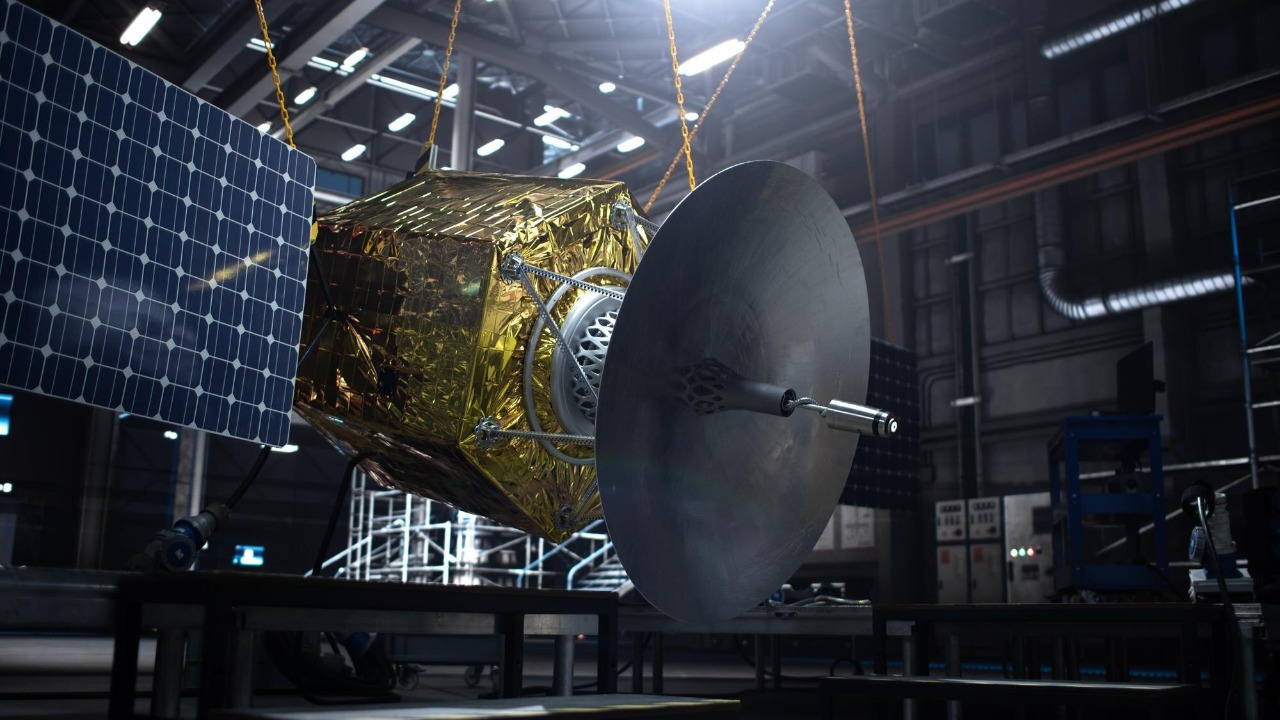

How orbital supercomputers would actually work

On paper, the architecture looks like a three layer stack: ground users, the existing Starlink internet constellation, and above that a new shell of AI optimized satellites. Once launched, these upper layer satellites aim to pack powerful computing hardware into orbit, connected by laser links to SpaceX’s Starlink network so that data can be shuttled between Earth, the internet layer, and the AI layer with minimal latency. Descriptions of the system explain that the orbital data center satellites would rely heavily on high bandwidth optical links, routing traffic through Starlink and then back down to users, effectively turning the existing broadband constellation into a backbone for orbital compute.

Technical outlines of the project describe “computing in the vacuum” as a way to separate the AI hardware from the constraints of Earth based facilities, with each satellite carrying its own compute, storage, and networking stack. The ambition is to create a modular system in which capacity can be added by launching more satellites, rather than by building new terrestrial campuses, and where upgrades can be rolled out through successive generations of spacecraft that incorporate advances in chips, launch, and software. One analysis of the plan notes that this approach would require tight integration of hardware, launch, and software, and that SpaceX is effectively betting that its control over rockets, satellites, and networking gives it a unique ability to build such a vertically integrated stack.

Regulators, rivals and the scale of the gamble

For all its technical bravado, the project still hinges on regulatory approval and geopolitical tolerance for a privately operated megaconstellation of unprecedented size. Musk’s SpaceX has applied to launch 1m satellites into orbit, and filings summarised by Reuters describe how the company is pitching the system as a way to deliver AI services to billions of users globally, a framing that is clearly designed to appeal to regulators who are weighing spectrum, debris, and competition concerns. The same filings emphasize that Elon Musk’s SpaceX has applied to build this network at a time when he is already the boss of Tesla and X and is widely described as the world’s richest person, a concentration of power that some policymakers may see as a reason to scrutinize the proposal more closely, as highlighted in reports that quote Reuters.

Financial and regulatory analyses also point out that SpaceX is seeking permission from the Federal Communications Commission to operate these solar powered satellite data centers, arguing that they will be more efficient and less carbon intensive than terrestrial rivals. One filing notes that the company has already demonstrated its ability to reuse rockets, with some boosters flying 11 times since 2023, and that this reusability is central to making the economics of a million satellite constellation viable, a point underscored in regulatory summaries. At the same time, critics quoted in coverage of the application warn that launching such a vast number of satellites could worsen space congestion and complicate astronomy, echoing earlier concerns about Starlink but on a far larger scale.

From Star Wars metaphors to Kardashev dreams

Commentators have been quick to reach for science fiction metaphors to describe the project, with some likening Musk’s vision to a kind of “Star Wars” style orbital infrastructure that blurs the line between communications, computation, and energy capture. One detailed account explains that once the new satellites are in place, they will sit above the existing Starlink layer, using laser links to move data between the AI supercomputers and the internet satellites that already provide access to millions of users, effectively turning the current broadband constellation into a gateway for orbital AI services that can be accessed from the same dishes that today connect homes and ships to Starlink.

More from Morning Overview