Biologists have long suspected that aging is not just a slow, inevitable fraying of our cells but a process governed by specific molecular switches. A growing body of research now points to individual proteins that appear to decide when cells stop dividing, when tissues begin to fail, and even how aging signals travel through the bloodstream. Together, these findings are turning the abstract idea of “cellular aging” into a concrete set of targets that scientists can measure, manipulate, and potentially control.

At the center of this shift is the claim that a single protein can, in effect, call time on a human cell’s youth. Around that discovery, other teams are mapping a wider cast of molecules that either accelerate decline or hold it at bay, from gatekeepers of DNA stability to circulating messengers that spread damage from organ to organ. I see a new picture emerging in which aging is less a mystery of years and more a network of proteins that can be tuned, blocked, or boosted.

ATM: the guardian that tells cells when to grow old

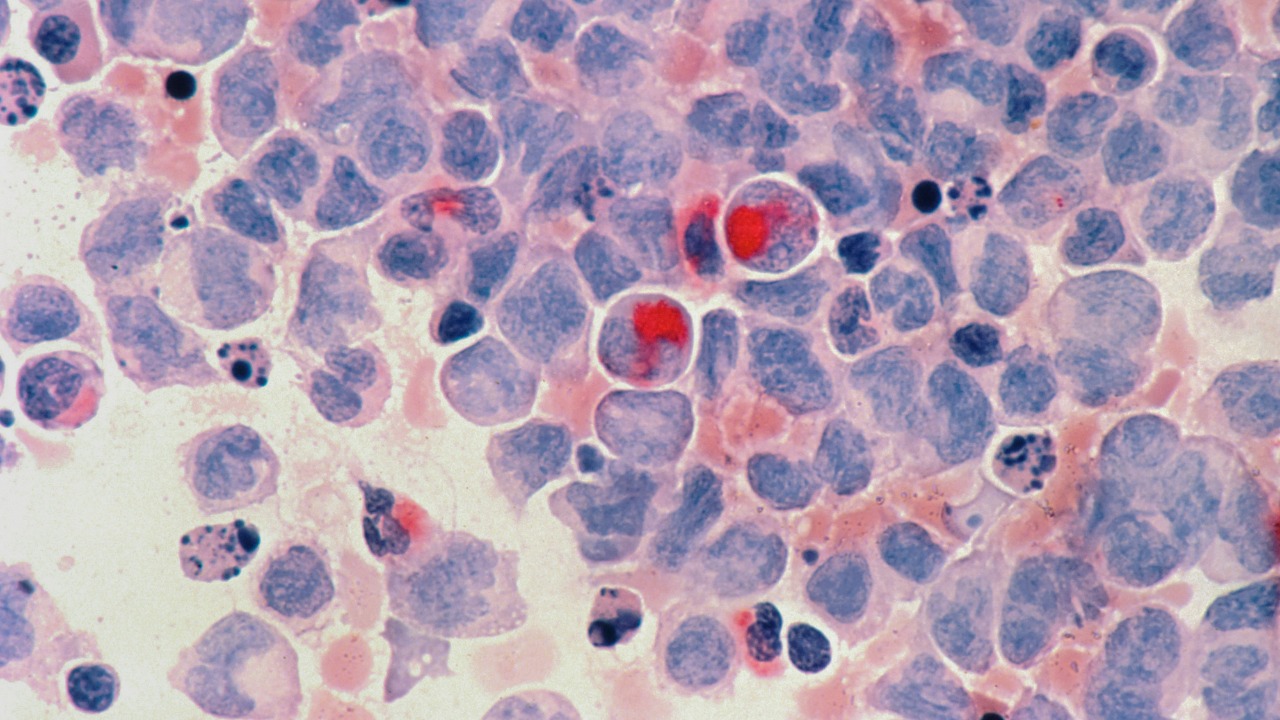

The most striking recent claim is that one protein, ATM, can single-handedly enforce a key form of cellular aging. In work highlighted in a Study, researchers report that ATM alone is responsible for driving telomere based senescence, the state in which cells permanently stop dividing after their chromosome ends become critically short. This protein is already known as a cancer guard because it senses DNA damage and helps prevent cells with broken genomes from multiplying, but the new data suggest that when telomeres erode, ATM does more than protect against tumors, it actively locks cells into old age.

What makes this finding even more consequential is the role of oxygen. The same report notes that high oxygen levels make this cancer guard hyperactive, which means ATM can be pushed into overdrive in environments that are more oxidizing than the low oxygen conditions where many cells normally reside. In practical terms, that links the protein’s decision to age a cell with the broader redox state of tissues, hinting that ATM sits at the crossroads of DNA integrity, oxidative stress, and the timing of cellular retirement. If that interpretation holds, then dialing ATM activity up or down could become a way to either reinforce the body’s defenses against cancer or, more provocatively, to delay the onset of senescence in vulnerable cell populations.

AP2A1: a “master switch” between senescence and rejuvenation

While ATM appears to decide when telomere damage becomes a point of no return, another protein, AP2A1, is emerging as a direct toggle between old and young cell states. In a set of Highlights from experimental work on fibroblasts, AP2A1 is described as being upregulated along stress fibers in replicative senescent cells, the structural filaments that become prominent as cells enlarge and stiffen with age. Crucially, the same report states that Knockdown of AP2A1 reverses senescence, shrinking those bloated cells back toward a more youthful size and promoting features of cellular rejuvenation. That is not just slowing decline, it is flipping an aged cell back toward a functional, dividing state.

A separate summary goes further and characterizes AP2A1 as a master regulator of this transition. According to a report that asks whether scientists have found a cellular “master switch,” Researchers discovered that AP2A1 controls whether cells enter senescence or revert to a more normal, proliferative state. When AP2A1 levels are reduced, senescent cells not only shrink but resume division, suggesting that this single protein sits high in the hierarchy of aging pathways. Taken together, these findings position AP2A1 as a potential lever for therapies that do not just prevent aging, but actively roll it back at the cellular level.

From lab bench to anti-aging strategy: AP2A1’s therapeutic promise

The idea that AP2A1 can reverse senescence is not just a curiosity, it is already being framed as a blueprint for future interventions. In work led by Researchers from Osaka University, the protein subunit AP2A1 is described as a key factor in the unique structure of senescent cells and their interaction with their environment. By mapping how AP2A1 shapes those stress fibers and the cell’s external contacts, the team is effectively identifying the handles that drugs or gene therapies might grab to remodel aged tissues. If AP2A1 can be tuned without disrupting its normal roles in healthy cells, it could become a central target in regenerative medicine.

Other scientists are already talking about AP2A1 in the language of clinical translation. The same Osaka University work frames the protein as a promising candidate for future anti aging treatments at the cellular level, precisely because it appears to modulate the balance between structural rigidity and flexibility in senescent cells. I see this as a shift from treating aging as a diffuse process to treating it as a set of discrete, engineerable states. Instead of broadly stimulating cell division, which risks cancer, a therapy that selectively lowers AP2A1 in senescent cells could coax them back into a healthier configuration while leaving normal cells largely untouched.

Aging signals in the blood: ReHMGB1 and the spread of decline

Even if individual cells can be rejuvenated, aging is not confined to isolated pockets of tissue. Evidence is mounting that the body carries pro aging signals through the bloodstream, effectively broadcasting distress from one organ to another. A Korean team has zeroed in on one such messenger, a specific chemical form of the HMGB1 protein called ReHMGB1. According to a report on how aging might travel through blood, The Korean team discovered that ReHMGB1 can move aging related signals far beyond the cells where they originate, affecting cells far from where it was released. That turns a local injury or stress into a body wide aging cue.

The functional impact of that signal becomes clear in animal experiments. In mice, Blocking ReHMGB1 with antibodies reduced cellular aging markers and improved physical performance after injury, according to a study that frames the protein as a potential target to slow or reverse age related decline. The report notes that Blocking this circulating factor not only dampened molecular signs of senescence but also translated into better physical outcomes. For anyone thinking about systemic anti aging therapies, ReHMGB1 looks like a crucial node, a protein that could be intercepted in the blood to protect distant tissues from the ripple effects of damage elsewhere.

Redox balance and oxygen: the chemical backdrop of aging proteins

Proteins like ATM and ReHMGB1 do not act in a vacuum, they operate within a chemical environment defined by the cell’s redox state. Classic work in biogerontology has argued that the redox state of cells is an expression of proton translocations across membranes and plays a central role in cellular bioenergetics. One influential analysis notes that the superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide are essential components of prooxidant signaling systems that help regulate healthy aging, not just cause damage. As that paper puts it, the redox state and these reactive species comprise the toti cellular bioenergy state and function, meaning they shape how every part of the cell behaves. Those concepts are laid out in detail in a study of the redox state and healthy aging.

This chemical backdrop helps explain why high oxygen levels can make ATM hyperactive and why oxidative stress is so tightly linked to senescence. When oxygen tension rises, the balance of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide shifts, altering the signals that DNA damage sensors and other proteins receive. I see this as a reminder that targeting a single protein will rarely be enough; any attempt to modulate ATM, AP2A1, or ReHMGB1 will have to account for the redox environment that tunes their activity. It also suggests that interventions that restore a youthful redox balance, whether through metabolism, diet, or drugs, could indirectly recalibrate these aging switches.

Other protein guardians of aging: NAD, Klotho, and more

ATM and AP2A1 may be grabbing headlines, but they are joining a crowded field of proteins already implicated in longevity. A survey of targets that scientists are pursuing to slow aging highlights six key proteins and pathways, including NAD⁺, SIRT6, and others that sit at the heart of cellular metabolism and DNA repair. In that overview, NAD⁺ (Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) is described as a small molecule found in all cells that helps enzymes produce energy and repair DNA, while extra SIRT6 extends lifespan in model organisms. These details come from a report on NAD and other proteins scientists are targeting.

Another standout is Klotho, often described as an anti aging protein in its own right. Experimental work in mice shows that Klotho deficient animals have accelerated aging phenotypes, whereas overexpression of Klotho extends lifespan. The same research notes that Klotho is an anti aging protein that, when present at higher levels, reduces the risk of age related diseases. These findings are detailed in an Abstract that lays out the biological role of Klotho and its impact on longevity. Together, NAD⁺, SIRT6, and Klotho illustrate that aging is governed by a network of metabolic and signaling proteins, not a single master molecule, even if some like AP2A1 and ATM occupy especially powerful positions.

The aging brain: proteins that slow decline and how to counter them

Nowhere are the stakes of cellular aging clearer than in the brain, where the loss of synapses and neurons translates directly into memory lapses and cognitive decline. Researchers have identified a protein that appears to slow the aging brain, but in this case “slow” means impede, not protect. A detailed report titled This Protein Slows the Aging Brain, We Know How, Counter It, By Levi Gadye, Aging describes how elevated levels of a specific factor in older brains correlate with poorer performance on memory tests. When scientists reduced that protein’s activity in animal models, the animals did better on memory tasks, suggesting that dialing it down could restore some youthful function.

What I find striking is how similar this logic is to the AP2A1 story. In both cases, a protein that rises with age appears to act as a brake on cellular or neural plasticity, and reducing its influence reopens a window for repair and growth. The brain study underscores that aging is not just about damage accumulation but also about active suppression of regenerative programs. If researchers can safely “counter” such proteins in humans, as the report’s title suggests, they might be able to extend the brain’s functional lifespan even if some underlying wear and tear remains.

Reversing cellular aging: from Korea University to future clinics

Beyond individual proteins, some teams are already sketching out how these discoveries might translate into therapies that slow or even reverse cellular aging. Scientists at Korea University have reported a new protein discovery that opens the door to such interventions, describing how manipulating a specific factor can slow the onset of senescence and potentially reverse tissue damage. Their work emphasizes that for decades, scientists have understood that cellular aging is driven by complex pathways, but only now are they identifying discrete proteins that can be targeted for future anti aging treatments. These claims are summarized in a report on how Scientists at Korea University are opening the door to slowing or reversing cellular aging.

These efforts sit alongside the AP2A1 and ATM findings as part of a broader push to move from descriptive gerontology to interventional geroscience. I see a pattern in which researchers first map how proteins like AP2A1, ATM, and ReHMGB1 behave in aging cells, then test whether tweaking them can restore youthful features in culture or in animals. The Korea University work suggests that this pipeline is beginning to yield candidates that could one day be formulated into drugs, gene therapies, or antibody treatments. The challenge will be to harness these powerful levers without tipping the balance toward cancer or other unintended consequences, a risk that is especially acute when interfering with proteins that guard the genome or control cell division.

One protein or many: what “master switches” really mean

With so many proteins now implicated in aging, the notion that a single molecule “decides” when cells grow old can sound overstated. Yet the ATM and AP2A1 findings show that some proteins do occupy privileged positions in the hierarchy of aging signals. ATM alone appears to enforce telomere driven senescence, while AP2A1 behaves like a master switch between senescence and rejuvenation in fibroblasts. ReHMGB1, for its part, seems to carry aging instructions through the blood, turning local stress into systemic decline. In that sense, each of these proteins can be seen as a decisive node in a particular branch of the aging network.

At the same time, the broader landscape of NAD⁺, Klotho, redox balance, and brain specific factors reminds me that no single protein explains aging in all its forms. Instead, what is emerging is a layered control system in which some molecules, like AP2A1, act as local toggles, others, like ReHMGB1, act as messengers, and still others, like ATM, act as guardians that trade off between cancer prevention and tissue renewal. The promise of this work is not that one protein will magically halt aging, but that by understanding these master switches in context, scientists can design targeted interventions that extend healthy function without sacrificing safety. For now, the discovery that a single protein can, in some settings, dictate whether a cell stays young or grows old is less a final answer than a powerful new starting point.

More from MorningOverview