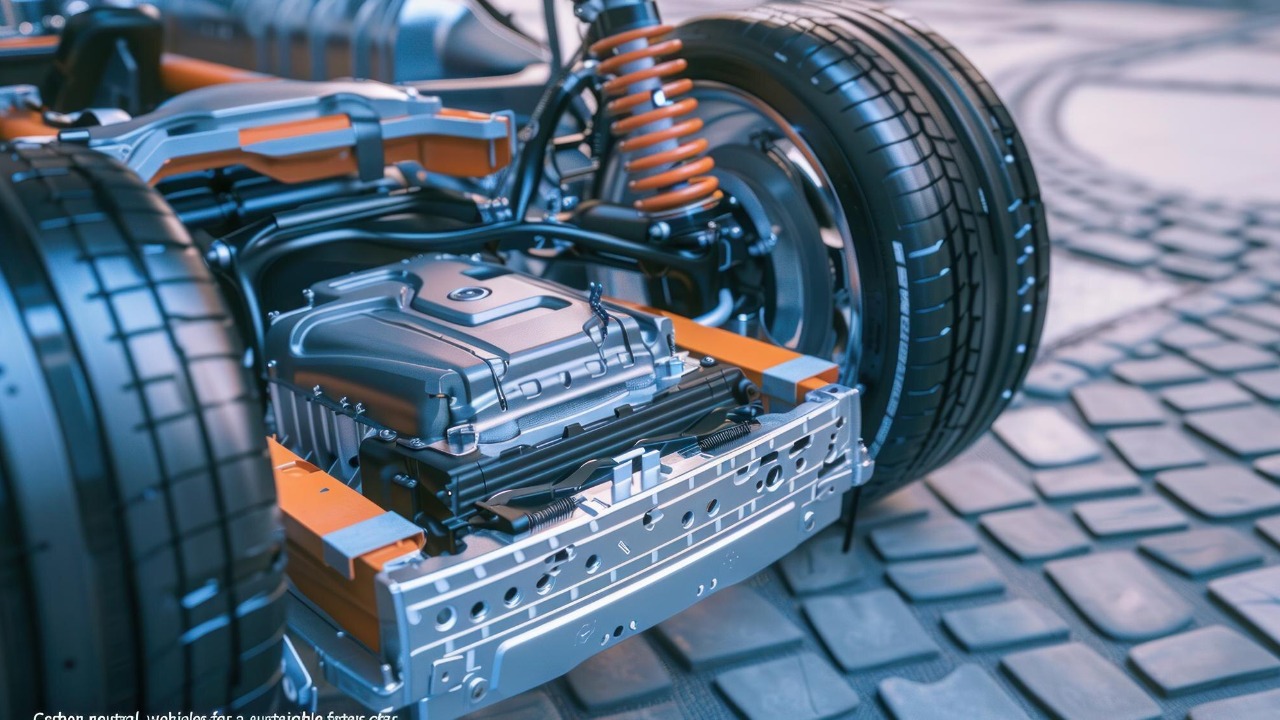

Electric vehicles are on the cusp of a battery shift that could matter more than any new model reveal or charging app. Silicon anodes, long hyped and just as long held back by basic physics, are finally moving from lab curiosity to products that promise far more range, faster charging and dramatically longer pack life. If the latest claims hold up in real cars, the technology could redraw the competitive map for automakers and reset consumer expectations for what an EV can do.

Instead of chasing marginal gains from today’s graphite-based cells, a new wave of companies is using silicon to pack more energy into the same footprint and to survive hundreds of thousands of miles of use. I see this as a potential inflection point, not because it makes for flashy headlines, but because it directly attacks the three anxieties that still slow EV adoption: range, battery longevity and cost over the vehicle’s life.

Why silicon anodes matter more than another range bump

Silicon has been the battery world’s tantalizing upgrade for years because it can store far more lithium than graphite, which is the workhorse material in most current EV anodes. In practical terms, that higher capacity means the same size pack can carry more energy, or a smaller pack can deliver the same range, both of which are powerful levers for automakers trying to squeeze efficiency out of every cell. The latest silicon designs are now being pitched as a way to deliver long-range EVs that do not need oversized, heavy packs just to calm drivers’ fear of running out of charge.

That promise is starting to show up in hard numbers. One Pioneering battery manufacturer has publicly tied its silicon-based chemistry to a projected 600,000-mile pack life, a figure that would have sounded fanciful only a few years ago. If a single battery can credibly last that long, it changes the economics of EV ownership, opens the door to multiple vehicle lifetimes for the same pack and makes high-mileage use cases like ride hailing or delivery fleets far easier to justify.

The physics problem: Silicon’s brutal expansion and contraction

The reason silicon has taken so long to reach this point is simple and unforgiving: the material swells and shrinks dramatically as it charges and discharges. Traditional graphite anodes already expand and contract during cycling, which limits battery life and performance, and that mechanical stress is one reason cells eventually lose capacity. As one technical analysis puts it, this repeated motion makes electrodes less stable and accelerates degradation, a problem that becomes more severe as energy density rises and the materials are pushed harder in each cycle.

Silicon magnifies that challenge. During charging, Silicon can expand and contract by as much as 300 percent, which pulverizes conventional electrode structures, breaks electrical contact and leads to rapid capacity fade. Indeed, during charging and discharging cycles, battery electrodes expand and contract in ways that make them less stable, and silicon’s extreme volume change has historically turned that manageable issue into a fatal flaw. Any claim of a silicon breakthrough, in other words, lives or dies on whether it has truly solved this durability problem rather than just masking it for a few dozen cycles.

Inside the new silicon breakthrough claims

The latest wave of announcements is notable because it focuses less on theoretical capacity and more on full-size cells that can survive realistic conditions. Two U.S.-based battery companies now say they have built silicon-anode cells that can match or exceed today’s EV performance while holding up under aggressive cycling and temperature swings. According to their joint disclosures, the companies claim that the new cells can deliver high energy density suitable for long-range cars and grid-scale storage, with commercial deployment targeted for EVs and energy storage systems in 2027, a timeline that would put silicon into mainstream vehicles within a single product cycle for many automakers.

Those claims are backed by specific test regimes rather than vague lab anecdotes. The partners describe cells that maintain performance across a wide temperature window and under fast charging, which has historically been a stress test that exposes silicon’s weaknesses. In their public materials, Two U.S.-based battery companies frame this as a step change rather than an incremental tweak, arguing that the combination of silicon anodes and refined manufacturing can finally deliver both energy density and cycle life at scale.

Group14, Porsche and the leap from lab to road

One of the most closely watched players in this space is Group14, which has spent years developing engineered silicon-carbon composites designed to tame the material’s expansion. Group14, a U.S. company backed by major automotive and energy investors, has now reported results from 20 Ah pouch cell tests that are sized much closer to real EV hardware than coin cells or tiny prototypes. In those tests, the company says its silicon-rich anodes can deliver high capacity while maintaining stability, a combination that has eluded many earlier efforts that either sacrificed durability or required exotic, expensive materials.

The automotive implications become clearer when you look at how these cells are being positioned alongside specific vehicles. Porsche-backed Group14 Technologies has highlighted silicon-anode performance in conditions that mirror what a premium EV would face, including high C-rate charging and operation at temperatures between 20C (68F) and 60C (140F). In public statements, Group14, a U.S. company backed by automotive partners, has framed these 20 Ah pouch cell tests as proof that its material can handle the thermal and mechanical stress of real-world driving rather than just controlled lab cycling.

From smartphones to sports SUVs: early silicon in the wild

While EV makers are still preparing their first silicon-heavy packs, the technology is already showing up in smaller consumer devices. Silicon-anode batteries are now powering high-end Chinese smartphones, where they are delivering blowout capacity that would put many current EV cells to shame on a per-kilogram basis. These phones are a useful proving ground because they combine fast charging, frequent cycling and tight packaging, all of which stress the battery in ways that reveal weaknesses quickly. The fact that manufacturers are comfortable shipping millions of such devices with silicon inside suggests that the material’s worst durability issues can be managed with the right design.

On the automotive side, there is a clear path from these early deployments to flagship electric models. Reporting around the upcoming Porsche Cayenne Electric has pointed to a big breakthrough in pack design that leverages silicon-rich anodes to deliver both performance and range in a large, heavy SUV. In that context, the reference to a Porsche Cayenne Electric: The battery is less about a single model and more about a template for how premium brands can use silicon to differentiate on acceleration, towing and long-distance comfort without resorting to oversized packs.

How silicon stacks up against solid-state and cathode breakthroughs

Silicon anodes are not the only next-generation battery technology vying for automakers’ attention. All-solid-state designs, which replace flammable liquid electrolytes with solid materials, promise even higher energy density and improved safety, and they are attracting major investment from established players. One partnership between two EV battery companies is explicitly focused on strengthening an all-solid-state materials business, with the companies already developing new cathode and electrolyte combinations that could pair with advanced anodes in future cells. In their joint roadmap, they describe a strategy that blends silicon, solid electrolytes and high-nickel cathodes to push performance beyond what any single innovation could deliver on its own.

Traditional manufacturers are also working on cathode breakthroughs that could reshape the market even without a full shift to solid-state. A high-profile collaboration around solid-state technology has highlighted how a new cathode material could transform the EV landscape, with analysts pointing to potential gains in range, charging speed and cost once the chemistry is mature. In that context, Now it is looking to strengthen its all-solid-state materials business, while separate reporting on Potential EV Market Impacts The cathode material breakthrough underscores how multiple battery fronts are advancing in parallel. Silicon’s edge is that it can be slotted into existing lithium-ion manufacturing lines more easily than a wholesale switch to solid-state, which gives it a near-term advantage even as the industry keeps one eye on longer-term technologies.

The environmental and supply-chain stakes of moving beyond graphite

Beyond performance, silicon anodes carry real implications for the environmental footprint of EV batteries. Today’s graphite mining is energy-intensive and often tied to regions with carbon-heavy power grids, which blunts some of the climate benefits of electric vehicles. Analysts who track the full life cycle of battery materials note that reducing dependence on mined graphite, or replacing a significant fraction of it with silicon derived from more abundant sources, could cut both emissions and geopolitical risk in the supply chain. That is one reason climate advocates are watching silicon closely, not just as a way to make EVs go farther, but as a tool to make their production cleaner.

Silicon also fits into a broader conversation about how EV batteries are used, reused and recycled over time. The rapid and widespread EV adoption across the transportation sector can be a significant accelerator to meet climate initiatives, but it also creates a wave of end-of-life packs that must be handled responsibly. Researchers studying third-party electric vehicle battery remanufacturing argue that better data on life cycle characteristics and opportunities is needed to design supply chains that can harvest remaining value from used packs. If silicon-based batteries really do last longer and retain more capacity after automotive use, they could be especially attractive for second-life applications like stationary storage, which would further improve their environmental profile.

Durability, safety and the road to 600,000 miles

For drivers, the most tangible question is whether a silicon-rich pack can truly last as long as the car, or even outlive it. The 600,000-mile claim from a Pioneering manufacturer is striking because it suggests a battery that could support multiple ownership cycles, from a new premium EV to a second-hand commuter and then perhaps to a commercial or rural use case. To get there, engineers are combining silicon with binders, conductive additives and protective coatings that absorb its expansion without letting the electrode crumble. They are also tuning charging protocols and thermal management so the cells are not pushed into the most damaging parts of their operating window too often.

Safety is the other non-negotiable. Higher energy density means more stored energy in the same volume, which can amplify the consequences of any failure. That is one reason companies like Group14 and its automotive partners are so focused on demonstrating stability across a wide temperature range and under fast charging, as highlighted in materials that describe how Porsche-backed Group14 Technologies has tested cells between 20C (68F) and 60C (140F). If those results translate into production packs that can shrug off abuse, silicon anodes will not just be a performance upgrade, they will be a trust-building technology that makes EVs feel as robust and predictable as the combustion cars they are replacing.

What this turning point means for automakers and drivers

For automakers, the emergence of credible silicon anode technology forces a strategic choice. Companies that move quickly can lock in supply agreements, design platforms around higher energy density and market longer warranties that reflect the new durability ceiling. Those that wait risk being leapfrogged on range and total cost of ownership, especially in segments like pickups and SUVs where battery weight and towing demands make every kilowatt-hour count. I expect to see a wave of announcements over the next product cycle as brands decide whether to adopt silicon in high-end models first or to spread the benefits across their mainstream lineups.

For drivers, the impact will show up less in chemistry jargon and more in everyday experience. A family that can buy an electric crossover with sports-sedan acceleration, 400-plus miles of real-world range and a battery warranty that stretches toward 600,000 miles will think very differently about the trade-offs of going electric. Fleet operators will run the numbers on vehicles that can rack up huge mileage without midlife pack replacements, while utilities eye second-life silicon packs for grid storage. If the technology lives up to its billing, the phrase “battery anxiety” may soon feel as dated as the idea that smartphones could not last a full day, and the silicon anode era will look like the moment EVs finally left their early-adopter phase behind.

More from MorningOverview