On November 16, 2004, NASA’s X-43A vehicle, powered by a scramjet engine, made a historic leap in aviation technology. The unmanned vehicle accelerated to a speed of Mach 9.6—nearly 7,000 miles per hour—over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Southern California in a groundbreaking hypersonic test flight that lasted just 10 seconds before splashing down. This achievement marked the first time a scramjet-powered aircraft reached such velocities under its own power, demonstrating the potential for future hypersonic travel but also highlighting the technology’s limitations in sustaining flight.

The X-43A Project Origins

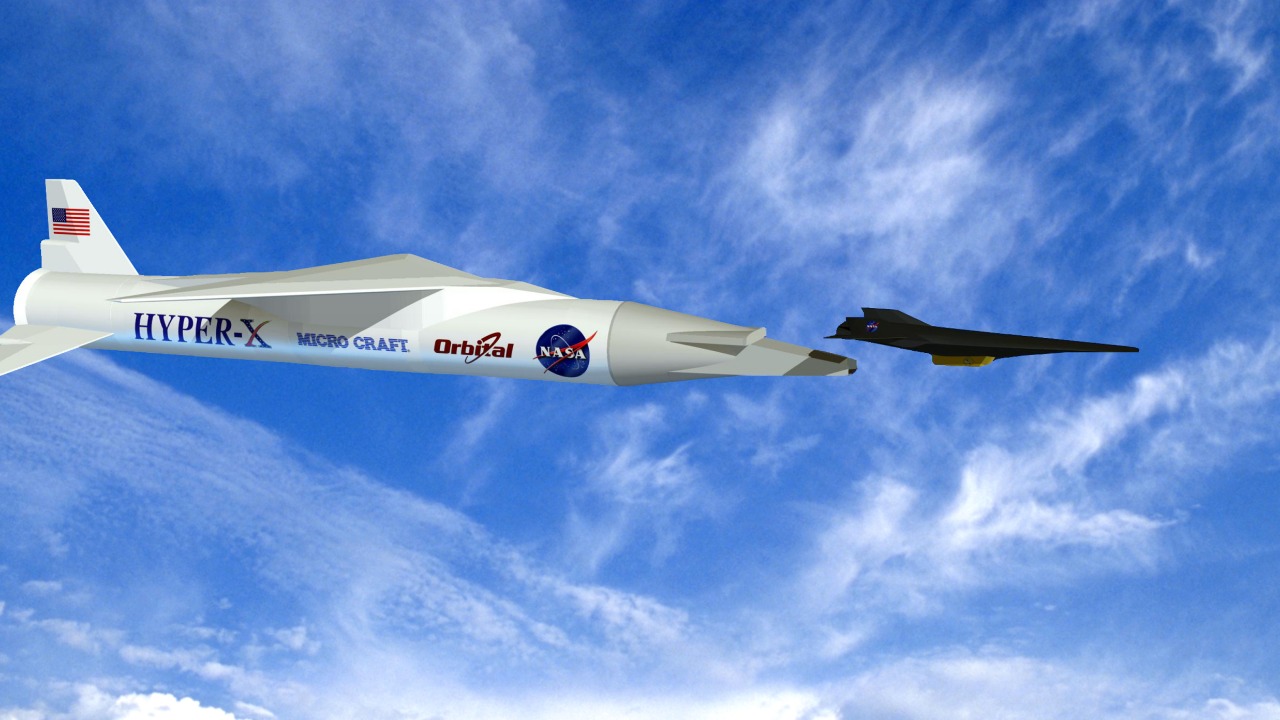

The X-43A project was a part of NASA’s larger Hyper-X program, which aimed to explore and validate technologies for air-breathing hypersonic flight. The program was a response to the need for faster, more efficient propulsion systems that could potentially revolutionize space travel and atmospheric flight. The X-43A, in particular, was designed to test the feasibility of scramjet engines, which had been theorized since the 1950s but had never been successfully demonstrated in flight.

The project was a multi-disciplinary effort involving experts in aerodynamics, materials science, and propulsion. The vehicle’s design was optimized for high-speed flight, with a flat, wedge-shaped body to minimize drag and a scramjet engine integrated into the vehicle’s body to maximize thrust. The project also involved extensive ground testing, including wind tunnel tests and engine tests, to validate the vehicle’s design and performance before flight.

Launch and Acceleration Sequence

The X-43A was launched from a modified B-52 bomber at an altitude of 40,000 feet over the Pacific Ocean near Edwards Air Force Base, California. A Pegasus booster rocket, provided by Orbital Sciences, separated from the aircraft and ignited to propel the X-43A to Mach 8 before the scramjet took over for the final acceleration phase.

Engine ignition occurred at approximately 70,000 feet altitude, allowing the vehicle to reach Mach 9.6 in seconds through supersonic combustion.

The booster rocket was jettisoned once it had expended its fuel, and the scramjet engine then ignited, propelling the X-43A to even higher speeds. The engine’s ignition was a critical moment in the flight, as it marked the first time a scramjet engine had powered a vehicle in flight. The engine operated for approximately 10 seconds, during which time the X-43A reached its top speed of Mach 9.6.

Key Performance Metrics

The X-43A achieved a top speed of Mach 9.68, equivalent to 9,680 feet per second or about 6,600 miles per hour at that altitude. However, the flight duration was limited to 10 seconds of powered flight, followed by a glide and descent into the ocean for recovery.

Despite the brief duration of the flight, the thermal protection systems on the vehicle withstood temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit during the hypersonic run.

The X-43A’s performance was monitored closely during its flight to gather data on the scramjet engine’s operation and the vehicle’s aerodynamics. Sensors on the vehicle measured a range of parameters, including air pressure, temperature, and acceleration, providing valuable data for the analysis of the flight. The data showed that the scramjet engine performed as expected, producing the necessary thrust to accelerate the vehicle to Mach 9.6.

One of the key performance metrics of the flight was the vehicle’s speed. The X-43A’s top speed of Mach 9.6 set a new record for an aircraft powered by an air-breathing engine, surpassing the previous record of Mach 6.7 set by the SR-71 Blackbird. The vehicle’s speed was a testament to the power and efficiency of the scramjet engine, demonstrating its potential for future applications in hypersonic flight.

Challenges and Technical Hurdles

Prior test flights in 2001 and March 2004 failed due to booster malfunctions and structural issues, delaying the successful Mach 9.6 run until the third attempt. Scramjet instability at hypersonic speeds required precise control of airflow and combustion, which limited the engine’s operational window to mere seconds.

Data recovery involved real-time telemetry from onboard sensors, with the vehicle designed as expendable to prioritize safety over reusability.

The X-43A project faced numerous technical challenges, from the development of the scramjet engine to the design of the vehicle itself. The scramjet engine, in particular, presented a significant challenge due to its operation at hypersonic speeds. The engine had to compress incoming air efficiently, ignite the fuel-air mixture reliably, and produce thrust consistently, all within the extreme conditions of hypersonic flight.

Another major challenge was the vehicle’s thermal protection system. The X-43A experienced extreme temperatures during its flight, with the vehicle’s surface reaching over 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The vehicle’s thermal protection system had to protect the vehicle and its internal components from these temperatures, while also being lightweight and durable. The successful flight of the X-43A demonstrated the effectiveness of the vehicle’s thermal protection system, contributing to the development of future hypersonic vehicles.

Implications for Hypersonic Technology

NASA program manager Victor Schneider described the flight as “a new milestone in aviation history,” emphasizing its role in validating scramjet concepts for potential military and civilian applications. The test data supported advancements in materials science, including carbon-carbon composites for heat resistance, influencing subsequent programs like the X-51 Waverider.

Despite the success, the short duration underscored the need for longer-duration engines to achieve practical hypersonic vehicles for rapid global travel or defense systems.

The X-43A’s successful flight had significant implications for hypersonic technology. It validated the concept of scramjet propulsion, demonstrating that scramjet engines could operate effectively in flight and produce the necessary thrust for hypersonic speeds. The flight also provided valuable data on hypersonic aerodynamics and thermal protection, contributing to the development of future hypersonic vehicles.

The X-43A’s flight also highlighted the challenges of hypersonic flight, such as the need for advanced materials to withstand the extreme temperatures and pressures of hypersonic speeds. The flight demonstrated the need for further research and development in these areas, spurring interest in hypersonic technology among researchers and industry. The X-43A’s flight was a milestone in aviation history, paving the way for the development of faster, more efficient propulsion systems.

Legacy and Future Prospects

The X-43A’s achievement built on earlier scramjet research from the 1960s but represented the first unassisted air-breathing hypersonic flight beyond Mach 5. Post-flight analysis by NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center team confirmed all primary objectives met, paving the way for international efforts in hypersonic propulsion.

Ongoing challenges include scaling the technology for manned or sustained missions, as noted in NASA’s Hyper-X final report released in 2006.

The X-43A’s successful flight left a lasting legacy in the field of hypersonic technology. It demonstrated the feasibility of scramjet propulsion, setting a new speed record for air-breathing engines and providing valuable data for future hypersonic vehicles. The X-43A’s flight also spurred interest in hypersonic technology, leading to increased research and development in this field.

The X-43A’s flight also highlighted the potential of hypersonic technology for future applications. Hypersonic vehicles could revolutionize space travel, allowing for faster, more efficient launches and reentries. They could also have applications in atmospheric flight, enabling rapid global travel and advanced defense systems. While there are still many challenges to overcome, the X-43A’s flight was a significant step towards the realization of these possibilities.