Drug discovery is shifting from static snapshots to moving pictures. Instead of inferring how medicines work from end results, researchers are now watching individual molecules collide with cell receptors and trigger signals in real time. That shift is beginning to expose why some drugs heal, others harm, and how to design the next generation to be both safer and more precise.

At the heart of this change is a suite of new imaging and tracking tools that let scientists follow receptors, signaling proteins and even single drug molecules inside living cells. I see a common thread running through these advances: they turn once invisible steps in pharmacology into measurable events, from the first binding at the cell surface to the final internalization of a receptor deep inside the cell.

From mystery switches to mapped pathways

For decades, clinicians have prescribed medicines that act on G protein coupled receptors with only a partial understanding of what happens after the pill is swallowed. These receptors are the targets of roughly a third of all prescription drugs, yet the choreography of how they activate and then release their G proteins inside cells remained hazy. Researchers at UNC have now filled in critical parts of that picture, showing in detail how common prescription compounds set off cellular responses through these receptors.

Until recently, scientists did not fully understand how the so called G proteins detach from drug activated receptors on the cell surface and move on to propagate signals. By combining live cell imaging with molecular tools, a team led by Jan in the pharmacology and computational medicine department has tracked this breakaway step as it happens, revealing how different drugs can bias the timing and strength of the signal. Their work, described by Jan as a bridge between structural biology and cell physiology, tackles a problem that had lingered in textbooks for years and is documented in detail in a report that notes how, until now, researchers lacked a clear view of this process Until.

Turning receptor traffic into a drug discovery engine

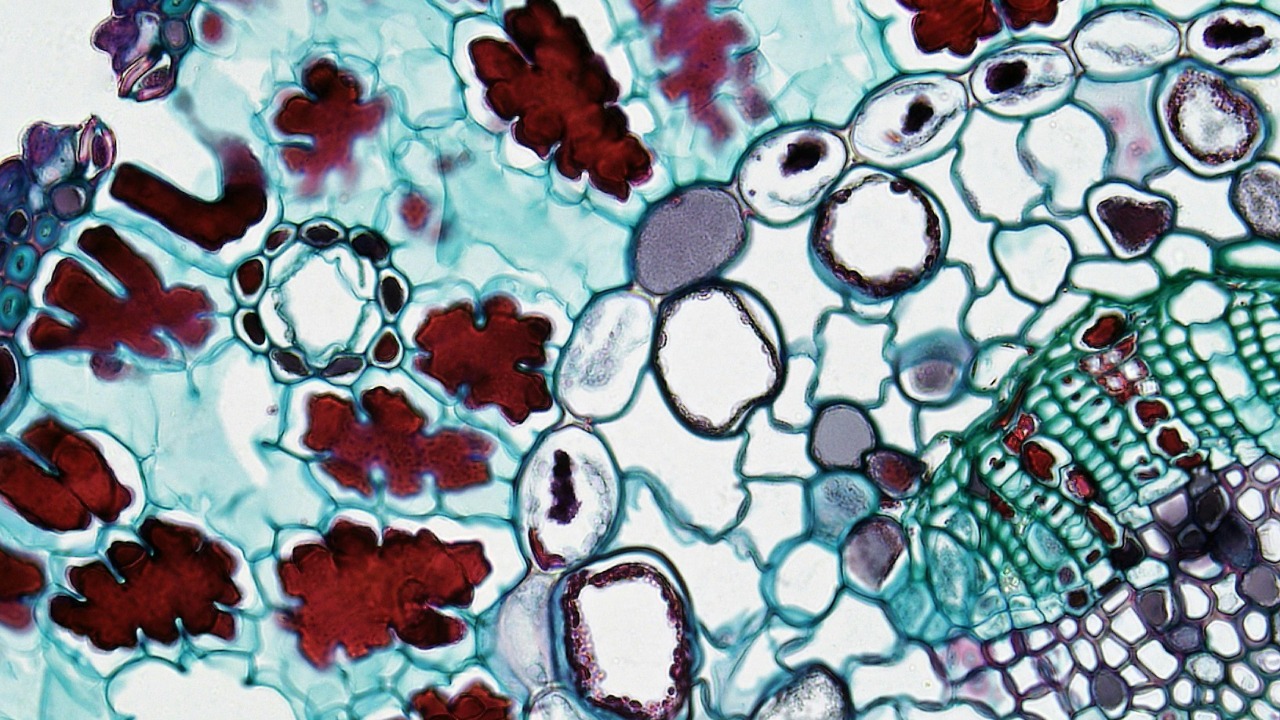

If understanding G proteins is about decoding the language of signals, another line of work treats receptor movement itself as a readout for drug action. A group of researchers has described what Mar called a powerful unrestricted and universal technology of drug discovery that is based on trafficking properties of plasma membrane proteins. Instead of measuring only downstream effects like gene expression, they monitor how receptors move, cluster and internalize in response to candidate compounds in real time living systems, turning cell biology into a high throughput screening platform Mar.

The process tracks how cell receptors are internalized into the cell as part of their normal function when they encounter a hormone, neurotransmitter or drug. By following this internalization step with sensitive imaging, the team can distinguish compounds that subtly tweak receptor trafficking from those that trigger full scale removal of receptors from the surface. That distinction matters, because it can separate molecules that desensitize a pathway from those that fine tune it. The researchers emphasize that using receptor internalization as a primary screening readout, rather than a side observation, is what makes this approach to membrane trafficking novel process.

Freezing opioid receptors in motion

Few drug targets illustrate the stakes of getting receptor behavior right as starkly as the mu opioid receptor. This protein sits on nerve cells and is the main gateway for both lifesaving pain relief and deadly side effects from opioids. Using cryogenic electron microscopy, a team led by Gati has effectively frozen the mu opioid receptor in different conformations as it responds to ligands, capturing structural changes that unfold as drugs bind and activate it. Gati has stressed that the implications extend far beyond opioids, because the mu opioid receptor belongs to one of the largest families of drug targets in the human body and serves as a model for how other receptors might flex and twist during activation Gati.

The same group has paired these frozen snapshots with computer simulations that replay the receptor’s movements at the nanoscale in real time. By stitching together static cryo electron microscopy frames with molecular dynamics, they can watch how different opioid molecules stabilize distinct shapes of the mu receptor, some associated with strong analgesia and others with respiratory depression. In my view, this kind of structural time lapse is what will allow chemists to design safer painkillers that favor beneficial conformations while avoiding those linked to overdose, a goal that is underscored in reporting on how the researchers used computer models to visualize receptor motion at the nanoscale in real time researchers.

Pinpointing where drugs land inside the body

While receptor centric studies reveal how targets move and change shape, another frontier focuses on the drugs themselves. Scientists at Scripps Research have devised a technique that shows in detail where drug molecules hit their targets in the body, mapping the precise tissues and cell types that accumulate a compound. By chemically tagging small molecules and then tracking their binding patterns, the team can see not just whether a drug reaches its intended receptor, but which organs and microenvironments it prefers. That level of spatial resolution turns vague notions of on target and off target effects into concrete maps of exposure Scripps Research.

In parallel, imaging specialists have begun to follow complex biologic drugs as they navigate cells. One group has developed fluorescently tagged versions of dual acting molecules that mimic the obesity drug tirzepatide, allowing them to watch how these compounds bind to receptors and move through intracellular compartments. Fluorescent probes illuminate drug pathways as they bind to specific cell types, revealing, for example, whether tirzepatide like molecules preferentially engage receptors on pancreatic beta cells or adipocytes. I see this as a crucial step toward understanding why some patients respond dramatically to such therapies while others see modest effects, a point that is reinforced by work using fluorescent probes to track how these drugs bind to specific cell types Fluorescent.

Single molecules, single receptors, and the future of safer drugs

All of these advances converge on a more granular view of pharmacology, and nowhere is that clearer than in single molecule tracking. Researchers have shown that following individual transmembrane receptors in living cells can reveal signaling functions that bulk measurements miss. By tagging single receptors and recording their trajectories, they can see when a protein switches from a freely diffusing state to a confined, signaling active cluster, or when it is corralled into endocytic pits for internalization. An Abstract of this work notes that single molecule tracking of transmembrane receptors in living cells has provided significant insights into signaling functions with previously untargeted mechanisms, highlighting how much hidden diversity exists even within a single receptor family Abstract.

When I connect that single molecule perspective with Jan’s live cell analysis of G proteins, Mar’s trafficking based screening, Gati’s cryo electron microscopy movies of the mu opioid receptor, the Scripps Research mapping of drug binding sites, and the fluorescent tracking of tirzepatide like molecules, a coherent future comes into view. Drug developers will not be satisfied with knowing that a compound lowers blood pressure or body weight in a trial. They will expect to see, in real time, how it docks with its receptor, how that receptor moves, how signaling proteins detach, which cells light up, and which conformations are stabilized. The promise is that by watching drug molecules hit cell receptors at this level of detail, I and other observers will be able to judge new therapies not only by whether they work, but by how precisely and safely they do so.

More from Morning Overview