Orbiting mirrors that can redirect sunlight have moved from science fiction concept to active business plan, promising brighter nights, more solar power and even new tools to fight climate change. The same technology could also flood the sky with artificial glare, disrupt ecosystems and undermine astronomy just as the universe is coming into sharper focus. I want to trace how this idea leapt from climate modeling papers into startup pitch decks, and why scientists now warn that lighting up the night could carry a price we are only beginning to tally.

The new business of selling sunlight

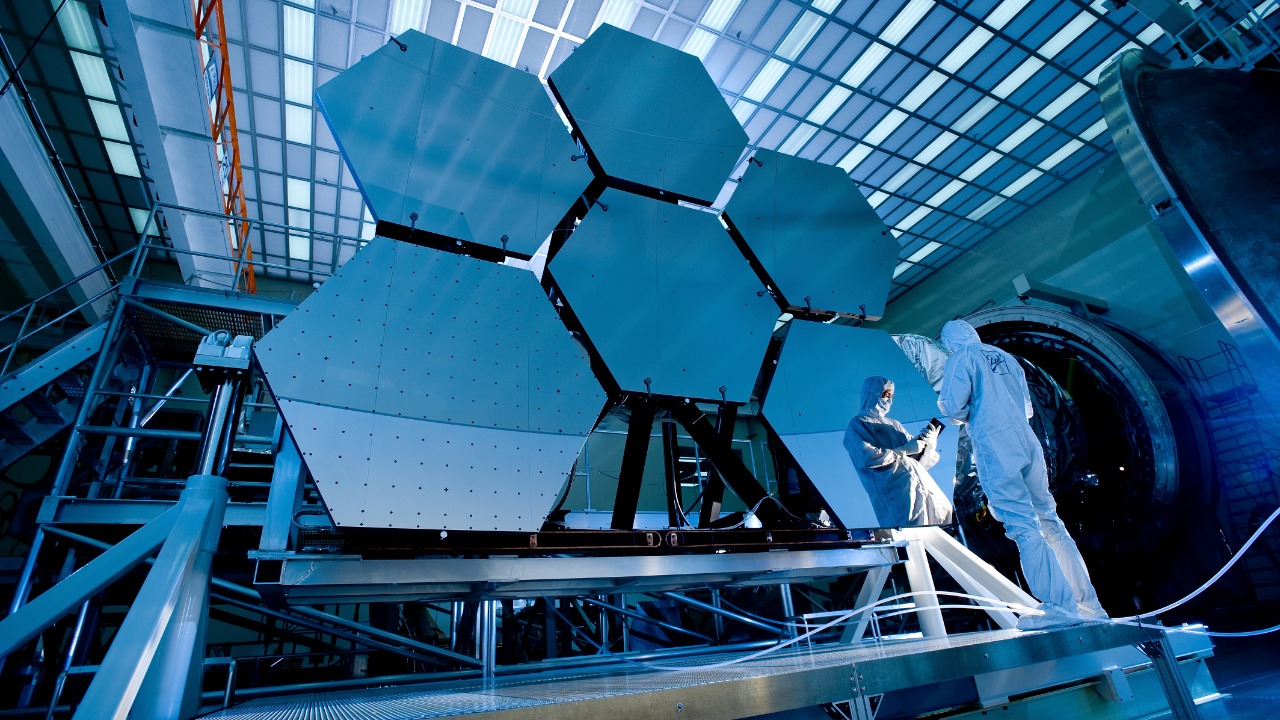

The most aggressive push to commercialize orbital mirrors is coming from a company that wants to turn sunlight itself into a subscription service. Reflect Orbital, described as a California based startup, has raised tens of millions of dollars to deploy thousands of reflectors that would redirect sunlight onto paying customers on the ground, from remote communities to industrial sites that want extra daylight after sunset. On its own site, the company pitches a constellation of controllable reflectors that could extend twilight, brighten disaster zones and deliver targeted beams of light to almost any point on Earth, framing the system as a flexible infrastructure layer rather than a one off experiment, a vision laid out in detail in its description of orbital light services.

Reporting on the company’s fundraising describes a plan to loft thousands of giant mirrors into orbit and then sell access to their redirected sunlight, with Reflect Orbital presented as a California based venture that has already secured 20 million dollars in backing for this effort. The same reporting notes that astronomers and other scientists have reacted with alarm, warning that a swarm of bright, actively steering reflectors could be catastrophic for scientific research that depends on dark skies and predictable satellite tracks. Those concerns are sharpened by the sheer scale of the proposal, which envisions thousands of units rather than a handful of test platforms, a scale that is central to the company’s pitch in coverage of Reflect Orbital, a California based startup.

From climate hack to orbital lighting grid

Long before anyone tried to sell sunlight, scientists were sketching out space mirrors as a radical way to cool the planet. In climate engineering circles, giant reflectors in orbit are grouped under space based solar radiation management, a family of ideas that would place reflective objects between Earth and the Sun to reduce the amount of energy reaching the surface. Analyses of these concepts stress that almost all studies agree such technologies would be very expensive, even if launch costs keep falling, and that the technical and political hurdles are so large that most research programs have shifted focus away from space based SRM toward other interventions, a judgment captured in assessments of almost all studies of these schemes.

Within that broader climate engineering debate, space mirrors are one tool among several that aim to manage incoming sunlight rather than greenhouse gases themselves. Work on solar radiation management emphasizes that these methods would directly mitigate the effects of atmospheric warming from burning fossil fuels by reflecting or blocking a portion of solar energy, lowering the warming effects from the Sun without touching emissions at their source. In that framing, orbital reflectors sit alongside ideas like stratospheric aerosols as part of a controversial toolkit that could, in theory, shave a fraction of a degree off global temperatures, a role summarized in descriptions of solar radiation management.

Decades of theory, and a sobering price tag

Space mirrors are not a new fantasy, and the technical literature is blunt about how hard they would be to build at planetary scale. When the Royal Society reviewed space based reflector concepts in 2009, it concluded that deployment times would be measured in decades and that the costs would be extremely high, even under optimistic assumptions about launch prices and materials. That assessment treated orbital mirrors as a last resort, not a quick fix, and it underscored that any serious attempt to shade the planet would require a sustained, multi generational engineering program, a conclusion embedded in the Royal Society’s summary of these options in 2009.

Even narrower proposals, such as placing a single large reflector at a stable point between Earth and the Sun, come with eye watering estimates. One widely cited concept for a space mirror at the L1 Lagrange point was projected to cost between trillions of dollars and require hundreds of thousands of launches on the most widely used launch vehicles, a scale that makes current commercial constellations look modest. Those figures help explain why, despite decades of discussion, no government has seriously attempted a full scale climate mirror, and why today’s commercial projects are targeting localized lighting and power applications instead of global cooling, a contrast that becomes clear in technical discussions of this proposal.

Mirrors as a climate bandage

Even if full scale planetary shading remains hypothetical, the climate logic behind space mirrors still shapes how scientists talk about them. The basic idea is straightforward: by reflecting a small fraction of incoming sunlight away from Earth, orbital mirrors could offset some of the warming caused by greenhouse gases, buying time while societies cut emissions. Advocates argue that in a world struggling to meet the 1.5 degree Celsius Paris Agreement goal, any additional lever to reduce net heating deserves at least careful study, a point that surfaces in discussions of giant mirrors alongside other technologies mentioned in the report such as aerosol injection.

Critics counter that treating orbital reflectors as a climate bandage risks distracting from the hard work of decarbonization and could introduce new hazards. A mirror system large enough to affect global temperatures would be a nightmare to maintain, vulnerable to collisions, malfunctions and political disputes over who controls the planetary thermostat. Report author and Star Technology president James Early, who studied such concepts, warned that even carefully tuned shading could shift weather patterns, potentially drying out regions like the Americas and northern Eurasia, a concern reflected in analyses that describe a space mirror as a nightmare to maintain.

Lighting up the night, and the sky science that depends on darkness

Where climate proposals imagine mirrors far from Earth, Reflect Orbital’s plan would place thousands of reflectors in low orbit, close enough to steer bright patches of sunlight across the surface. Astronomers warn that such a system could be catastrophic and horrifying for their work, not only because each mirror would be bright, but because the constellation would be actively directing light even after it passed over its intended target. One scientist noted that the reflectors will be directing their light even after they pass their target because they cannot shut the sunlight off, which from an astronomical perspective is pretty catastrophic, a blunt assessment captured in concerns that the reflectors will be directing their light.

Existing satellite constellations already create streaks and flares that contaminate astronomical images, and experts warn that adding thousands of giant mirrors would magnify those problems dramatically. Analyses of space mirrors for solar power note that current satellites cause light pollution and radio interference, and that a new layer of reflective hardware would further threaten ground based observatories that rely on dark, quiet skies. In that context, Reflect Orbital’s vision of orbiting mirrors reflecting sunlight down to specific locations on Earth is not just a clever energy idea, but a direct challenge to the fragile conditions that make precision sky surveys possible, a tension highlighted in technical discussions of how the existing satellites cause light and radio pollution.

Ecology under an artificial dawn

Beyond astronomy, scientists are increasingly worried about what an artificial second sunset would do to life on the ground. Past research on light pollution has shown that it can alter the behavior of a wide array of animals and plant species, from migratory birds that navigate by stars to insects that rely on darkness to feed and reproduce. When astronomers and ecologists look at a proposal to sweep bright beams of reflected sunlight across cities, farms and coastlines, they see a large scale experiment on circadian rhythms and seasonal cues that evolved under a predictable day night cycle, a concern rooted in findings that past research on light pollution has documented.

Public reaction is harder to gauge, but early signals suggest that the idea of engineered twilight is polarizing. One poll cited in coverage of the controversial startup’s plan found that people were sharply divided over whether they wanted extra sunlight sold to the highest bidder, especially if it meant more clutter in the night sky. For some, the promise of safer streets and more productive evenings is appealing, while others see the night as a shared commons that should not be carved up by private companies, a split that surfaces in reporting on a controversial startup’s plan to sell sunlight.

Who controls the beam?

Once mirrors can steer concentrated sunlight to specific spots on Earth, the question of who gets to aim them becomes unavoidable. Reflect Orbital’s own marketing materials describe potential applications that go far beyond clean energy or extended daylight, including support for emergency response, commercial operations and other services that would depend on precise control of when and where the beams fall. Reporting on the company notes that, in addition to describing the solar power boosting benefit of the technology, its website advertises other applications that have drawn interest from the U.S. Air Force as well, a detail that underscores how quickly a civilian lighting grid could blur into dual use infrastructure, as seen in coverage that highlights how in addition to describing the energy benefits, defense related uses are already on the table.

That prospect raises geopolitical and ethical questions that go well beyond the usual debates over satellite internet or Earth imaging. A constellation of steerable mirrors could, in principle, be used to dazzle sensors, interfere with adversary satellites or provide tactical illumination for military operations, even if it is marketed primarily as a civilian service. As with other space infrastructure, the line between commercial and strategic use is thin, and once the hardware is in orbit, governments will be tempted to lean on it in crises, whether or not the original designers anticipated that role. I find that the mere fact of U.S. Air Force interest, even at the level of exploratory conversations, signals that any large scale orbital lighting system will quickly become entangled in national security planning.

From speculative fix to contested frontier

Looking across the arc from early climate engineering papers to Reflect Orbital’s fundraising, I see a technology that has raced ahead of the public conversation about its risks. Space mirrors began as a speculative way to shave a fraction of a degree off global temperatures, with the Royal Society and other bodies stressing that deployment would take decades and cost staggering sums. Now, a California based startup is pitching thousands of reflectors as a near term business, even as climate intervention experts warn that almost all studies agree space based SRM would be very expensive and politically fraught, and that research has largely shifted away from it toward other options.

At the same time, astronomers, ecologists and civil society groups are scrambling to articulate what is at stake if the night sky becomes a canvas for commercial lighting. Their warnings about catastrophic impacts on scientific research, wildlife behavior and the shared experience of darkness are not abstract, they are grounded in years of data on light pollution, satellite interference and the fragility of ecosystems tuned to natural cycles. As I weigh those concerns against the promise of more solar power and extended daylight, the core question is not whether scientists want giant space mirrors, but who gets to decide how bright the future night will be, and what costs we are willing to accept to bend sunlight to our will.

More from MorningOverview