For decades, cardiology textbooks treated heart damage as permanent, a grim one-way street from heart attack to heart failure. A wave of new research is now overturning that assumption, revealing that the human heart carries dormant repair programs that can be switched back on. Scientists are not just slowing decline, they are beginning to show how injured hearts might rebuild living muscle.

The emerging picture is that our hearts retain a limited but real capacity to regenerate, and that capacity can be amplified with the right molecular nudges, stem cell tools, and bioengineered scaffolds. I see a field moving from managing damage to actively restoring function, with early findings in genes, cells, and even frogs hinting at therapies that could change what survival after a heart attack looks like.

The quiet revolution in cardiac regeneration

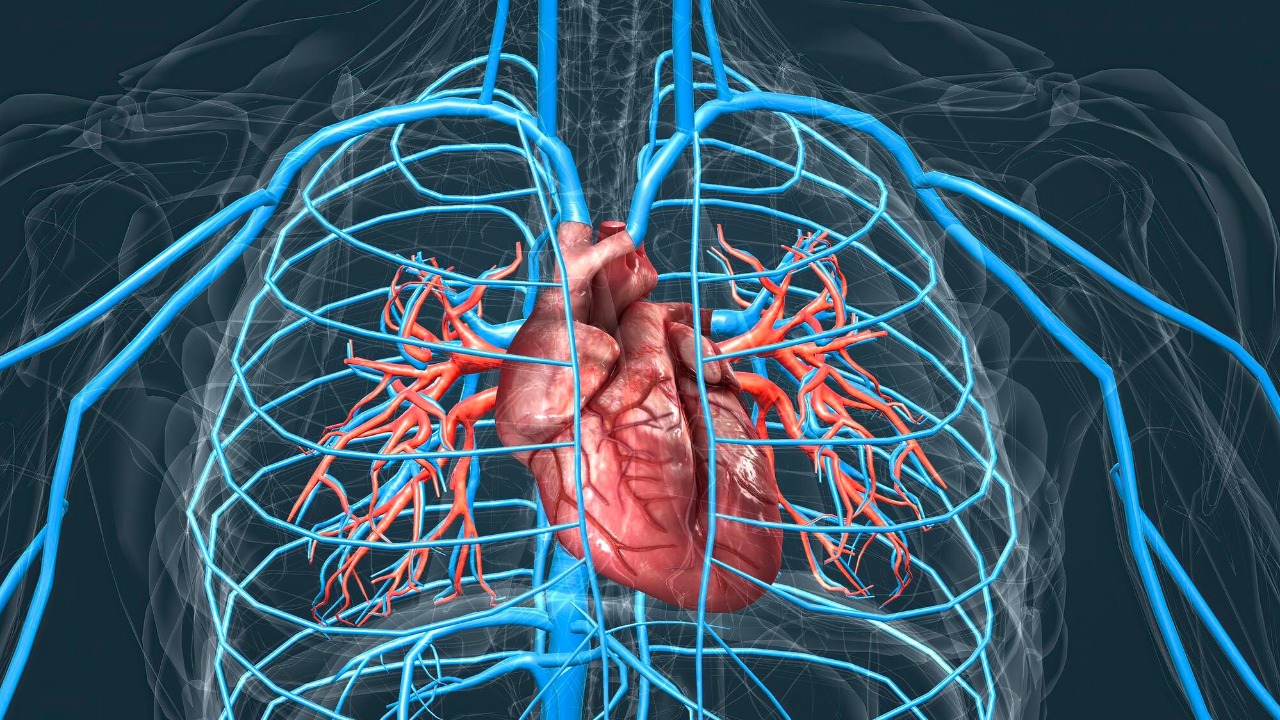

Cardiologists once believed that adult heart muscle cells were fixed in number, which meant every heart attack carved away function that could never be replaced. One of the major advances in cardiology research has been the recognition that the adult mammalian heart is in fact endowed with regenerative capacity, even if that capacity is too weak to offset the massive cell death that follows severe disease. Instead of a static pump, the heart is now seen as a dynamic tissue where cells are quietly turning over, and where the right signals might tilt the balance from scarring toward renewal.

That shift in basic science is starting to show up in human-focused studies that track how hearts respond after major injury. Researchers following patients with severe heart failure have found signs that the organ tries to heal itself by forming new muscle cells, although the response is patchy and often overwhelmed by fibrosis. In one line of work, scientists studying failing hearts reported that the rate of new cell formation was higher than in healthy hearts, suggesting there is a latent repair mechanism that could be boosted rather than written off as irrelevant.

A dormant gene that turns heart cells back into builders

One of the most striking discoveries in this space centers on a naturally occurring human gene called Cyclin A2, also known as CCNA2. This gene is active during fetal development, when the heart is still growing, but it turns off after birth in humans, which coincides with the point when heart muscle cells largely stop dividing. Researchers have now shown that Cyclin A2 can actually make new, functioning heart cells when it is reactivated in damaged tissue, effectively turning back on a program that evolution put into storage. In laboratory models, reawakening this gene has helped injured hearts generate fresh muscle instead of relying solely on scar tissue, according to work highlighted in a detailed research summary.

Scientists have taken that insight further by directly manipulating CCNA2 in human heart cells. By reawakening a dormant gene known as CCNA2, which produces a protein called cyclin A2, researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York have coaxed human heart cells in a laboratory to start dividing again, something long thought impossible. A related technique harnesses the power of Cyclin A2 in damaged hearts, using targeted delivery to push cells that had exited the cell cycle back into a proliferative state, as described in work from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai that details how the technique was applied after experimental heart attacks.

These gene-based strategies are not just curiosities at the petri-dish level. A separate report on human heart health notes that scientists have already used a reawakened gene to help heart cells repair themselves after injury, pointing to CCNA2 as a key driver of this effect. In that work, the heart could repair itself with help from a dormant gene, potentially helping heart attack patients by turning surviving cells into active builders rather than passive bystanders, a concept captured in coverage of how scientists are reframing post-attack care.

Hidden repair programs inside the failing heart

While gene reactivation offers a powerful lever, another strand of research suggests the heart is already trying to heal itself from within. Investigators studying tissue from patients with advanced heart failure have found that the number of newly formed heart muscle cells is higher in diseased hearts than in healthy ones. That counterintuitive finding implies that severe stress may kick-start a repair mechanism that lies mostly dormant under normal conditions. The challenge, as one group of researchers has argued, is that this endogenous response is too weak and too disorganized to restore full function, which is why they are exploring ways to kick‑start the repair rather than replace it outright.

That idea dovetails with broader work on myocardial regeneration that has cataloged the molecular pathways controlling whether heart cells divide, enlarge, or die. Chemical biology approaches have mapped out signals that can tilt adult heart cells back toward a regenerative state, including growth factors, small molecules, and cell cycle regulators. One influential analysis of myocardial regeneration emphasized that the adult heart’s limited renewal is not zero, but simply insufficient to offset the cell death in heart disease, and that targeted interventions could amplify this baseline activity, as detailed in a comprehensive review of the field.

From stem cell patches to whole‑organ repair

Genes are only part of the story. I am also watching a surge of work that uses living cells and engineered materials to physically rebuild damaged heart muscle. One promising approach involves a stem cell patch that can be laid over injured areas of the heart, providing both structural support and a reservoir of cells that can integrate with native tissue. Researchers have identified a new stem cell patch designed to gently heal damaged hearts, reporting that it can improve function while reducing the mechanical stress that drives further decline, according to a detailed description of the patch and its early testing.

Other teams are probing whether the heart’s own cells can be coaxed into a more regenerative mode without adding foreign material. A study from Arizona, for example, examined how certain signals could encourage heart tissue to repair itself after injury, concluding that the heart can heal itself under the right conditions and that therapies should aim to enhance that intrinsic response. The work, which focused on how cardiac cells respond to targeted molecular cues, has been summarized as evidence that the heart can heal itself when researchers supply the right triggers.

What frogs, genes and future patients have in common

Perhaps the most surprising connection in this story comes from outside cardiology altogether. In a striking experiment, scientists helped frogs regenerate amputated legs using a cocktail of drugs delivered through a wearable device, effectively decoding and awakening dormant signals that enable the body to regenerate parts of itself. The work has been framed as a step toward helping people regrow body parts, and it underscores a broader principle that applies directly to the heart: complex organs may retain latent instructions for repair that can be reactivated with the right combination of cues, as argued in an analysis of how such regeneration could extend life and improve its quality.

When I connect that insight back to Cyclin A2, stem cell patches, and the subtle uptick in new cell formation seen in failing hearts, a coherent picture emerges. The human heart may not match a salamander’s limb or a frog’s leg in raw regenerative power, but it is not the inert organ medicine once assumed. A naturally occurring gene called Cyclin A2 (CCNA2), which turns off after birth in humans, can be reawakened to make new heart cells, as detailed in a focused account of that work. Combined with evidence that the human heart may have a hidden ability to repair itself that can be amplified, as suggested in studies of human tissue, the case for a future in which repairing a broken heart means actual biological repair, not just symptom control, is getting harder to dismiss.

More from Morning Overview