Pancreatic cancer has long been one of medicine’s most unforgiving puzzles, killing most patients within a few years and often within months. Now a cluster of advances is giving researchers something they have rarely had in this disease: a clear mechanistic clue to how it might finally be beaten. At the center of that shift is a new strategy that does not just poison tumor cells, but systematically dismantles the defenses that make this cancer so hard to treat.

Instead of relying on a single “magic bullet,” scientists are converging on a more nuanced view of pancreatic tumors as shape‑shifting ecosystems that must be exposed, disarmed and then attacked. From triple‑drug combinations that erase tumors in mice to breath tests and bacteria‑based therapies, the field is starting to look less like a stalemate and more like a coordinated campaign.

The triple‑therapy experiment that changed the mood

The most striking recent signal comes from a team in Spain that set out to see what would happen if they hit pancreatic tumors at several weak points at once. In animal models, their triple‑therapy regimen did not just slow growth, it drove full regression of established tumors, a result that has been vanishingly rare in this cancer. The researchers reported that the combination eliminated pancreatic tumours in mice, suggesting that the disease may finally yield when its layered defenses are attacked in concert rather than in isolation, a finding detailed in one triple therapy report.

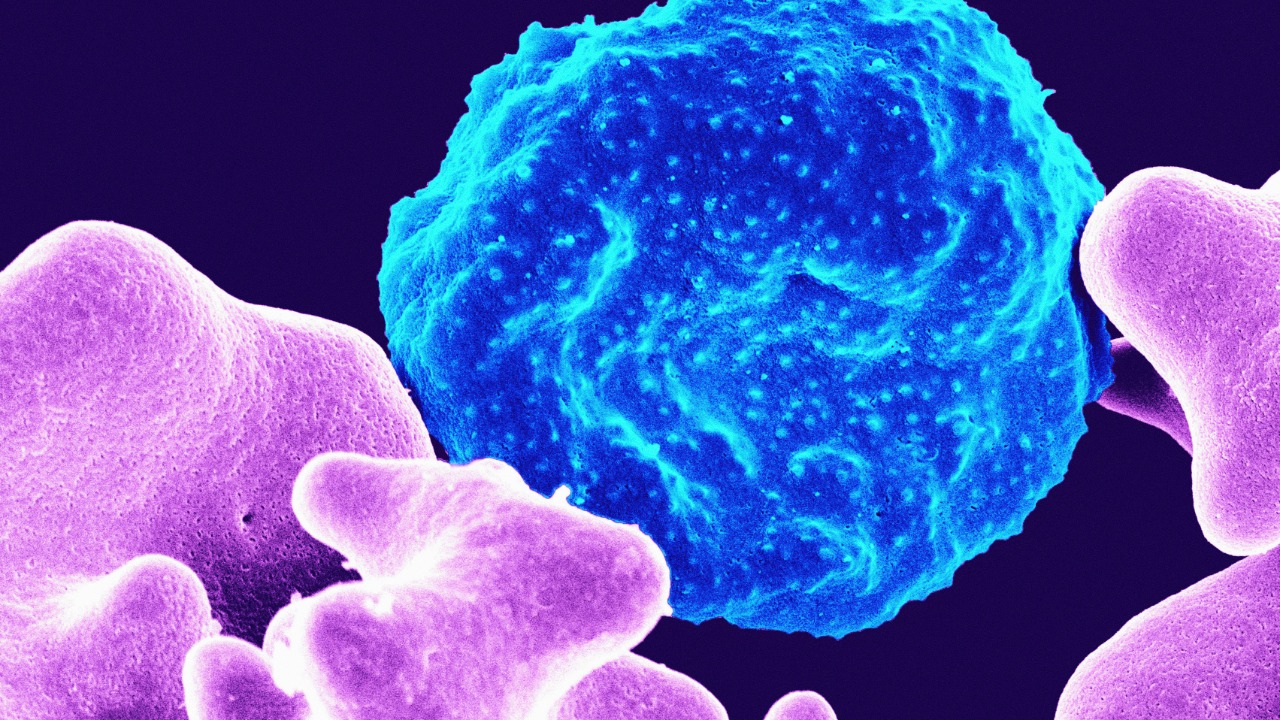

What makes this approach so important is not just the headline result, but the logic behind it. The Spanish group focused on how pancreatic tumors, which are among the most lethal of all cancers, surround themselves with dense scar‑like tissue and immune‑suppressing cells that block drugs and immune attacks. By combining agents that target the cancer cells, the supporting stroma and key signaling pathways, they were able to prevent the tumor from simply rerouting around a single blocked pathway, a concept further explained in a second account of the Spain study.

Cracking KRAS and the tumor’s hidden architecture

Underneath that strategy lies a more fundamental insight: pancreatic cancer is driven in most patients by a warped version of a single gene, KRAS, that does far more than tell cells to divide. When KRAS is mutated, it reshapes the entire neighborhood around the tumor, recruiting fibroblasts, immune cells and extracellular matrix in ways that shield the cancer from chemotherapy and immunotherapy. One analysis of this work notes that a mutated KRAS warps a tumor’s surroundings so that treatments rarely work and leads to very poor prognosis, a pattern that has frustrated oncologists for decades.

Recently, I have seen researchers like Barbacid and colleagues argue that the only way to change outcomes is to treat that distorted microenvironment as aggressively as the cancer cells themselves. Their work, which has circulated widely in scientific circles, emphasizes that targeting KRAS alone is not enough if the fibrotic shell and immunosuppressive cells remain intact. The Spanish triple‑therapy experiment fits squarely into that logic, as do other efforts that try to make hidden tumor deposits visible and vulnerable, including new findings that suggest future drugs could be used to make tumours visible and vulnerable to treatment, reshaping what we know about cancer biology according to one Jan report.

From lab bench to bedside: why caution still rules

For all the excitement, the scientists behind these breakthroughs are careful to stress that mice are not people. The Spanish team has been explicit that, although experimental results like those described in their work have never been obtained before, they are still not in a position to carry this exact protocol into clinics. In one detailed summary, they note that the new research uncovered a potential way to help the immune system more effectively attack pancreatic tumors, but they frame it as a path toward future therapies rather than a ready‑made cure, a nuance highlighted in coverage of the Jan findings.

That caution is echoed by other researchers who have described their own work as a major step toward a cure, but not the cure itself. A group of investigators wrote in a statement that they believe they have made a major breakthrough toward finding a cure for pancreatic cancer, while acknowledging that patients still face grim odds in the last year of the cancer, a balance captured in one breakthrough account. They later reiterated that position, emphasizing that they have raised hopes for a cure but must still navigate the brutal biology that makes this disease so lethal in the first place, as reflected when They described the final year of illness.

Finding the cancer earlier and making it easier to hit

Even the most elegant therapy will fail if it arrives too late, and pancreatic cancer is notorious for staying silent until it has spread. That is why a separate line of research is focusing on detection, including a quick and easy breath test that analyzes volatile compounds exhaled by patients. One report describes how a breakthrough test could put scientists a breath away from beating pancreatic cancer by revealing the presence of cancer through specific signatures in a person’s breath, a concept laid out in a breath test summary.

That same work has been described as a breakthrough test that could reveal the presence of cancer long before symptoms appear, potentially shifting diagnosis from late‑stage emergencies to manageable early disease. The idea is that a noninvasive screening tool, used in primary care clinics or even pharmacies, could flag high‑risk individuals for imaging and follow‑up, an approach that would complement the therapeutic advances rather than compete with them, as outlined in a second account of the Breakthrough tool.

Turning bacteria and big‑center expertise into weapons

While some teams refine drugs and diagnostics, others are experimenting with living therapies that can home in on tumors from the inside. Scientists have begun testing common bacteria as a weapon to target pancreatic tumors, engineering microbes that thrive in the low‑oxygen, nutrient‑poor niches where cancer cells hide. In one early‑stage program, investigators reported that these bacteria could be harnessed as a form of immunotherapy in a disease where fewer than patients live longer than five years after diagnosis, a stark statistic highlighted in coverage of how Scientists are testing this approach.

These experimental therapies are increasingly being coordinated through major academic centers that have spent decades building expertise in this infamously difficult disease. After decades of effort in pancreatic cancer research, Columbia researchers, for example, are now leading several breakthroughs in the infamously difficult disease, integrating surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and novel agents in tightly designed trials, as described in an overview of work at After Columbia. Their efforts sit alongside the Spanish triple‑therapy research, the KRAS‑focused microenvironment studies and the detection advances, forming a multi‑front campaign that finally feels proportionate to the threat.

More from Morning Overview