Earth’s magnetic field is quietly, steadily changing, and the shift is no longer just an abstract concern for geophysicists. As the protective shield that deflects charged particles from the Sun weakens and drifts, scientists are probing what a future geomagnetic flip could mean for satellites, power grids, navigation and life at the surface. The picture that emerges is less an instant doomsday than a drawn out stress test of the systems that modern civilization depends on.

Researchers now see signs that the field is evolving in ways that resemble the early stages of past reversals, when north and south magnetic poles swapped places. I find that the most striking message from the data is not that catastrophe is imminent, but that the next few centuries could bring a more restless, uneven magnetic shield, with consequences that will be felt first in orbit and in the high atmosphere before they touch daily life on the ground.

What a geomagnetic flip actually is

At its core, a geomagnetic reversal is a reorganization of the molten iron dynamo churning inside Earth, which causes the magnetic poles to wander and, eventually, to trade places. Geological records show that this has happened many times, and simulations by researchers such as Glatzmaier indicate that the process can involve several “false starts,” with the field weakening, recovering and changing shape before a full flip takes hold, a behavior described in detail in work on Earth. During these episodes, the overall strength of the field can drop significantly, and the familiar dipole pattern that guides compasses can fragment into multiple poles.

Contrary to popular disaster scenarios, the scientific consensus is that such a reversal unfolds over thousands of years, not overnight, and that life has persisted through countless flips. Analyses that ask bluntly “Are we all going to die?” answer with a wry “Yes,” but only in the sense that mortality is universal, not because a Magnetic Field Flip is expected to wipe us out. The real stakes lie in how a weaker, more chaotic field interacts with our technology and with the radiation environment around the planet.

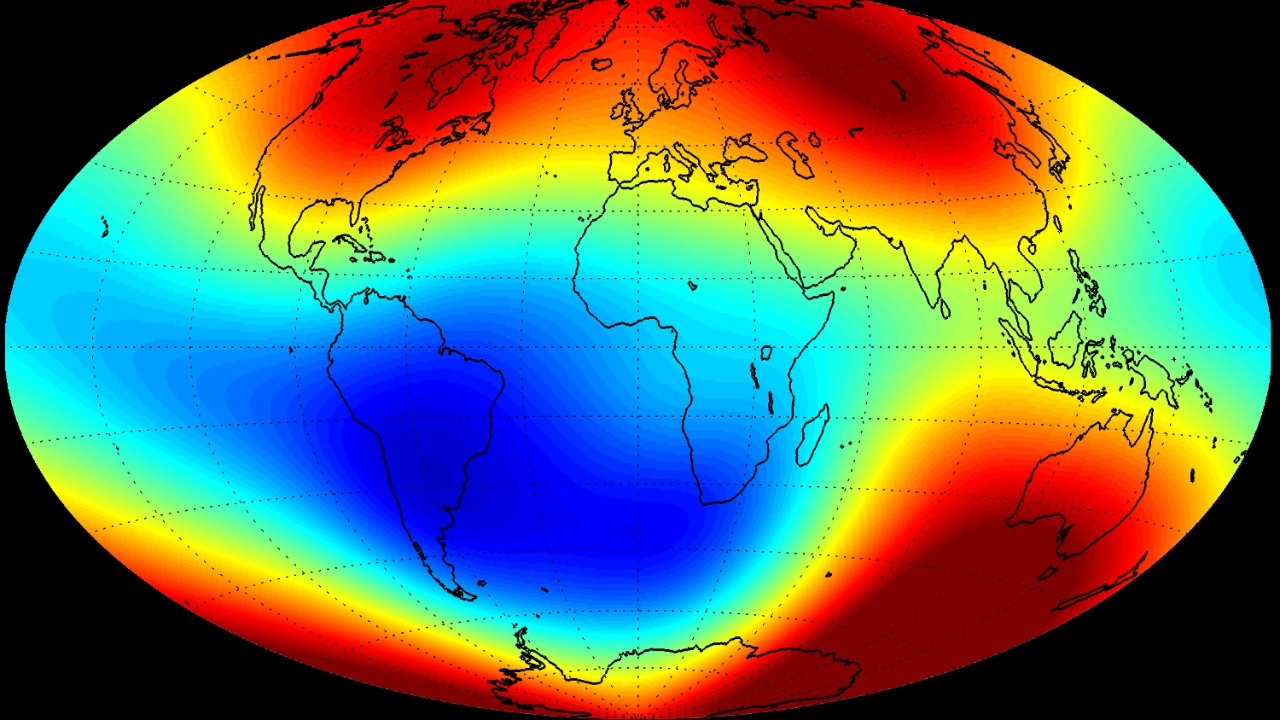

The field is weakening and developing a strange scar

Measurements from satellites and observatories show that Earth’s magnetic field is not only drifting, it is also weakening in specific regions. One of the most scrutinized anomalies is a broad low in field strength over the South Atlantic and parts of South America and Africa, a region often called the South Atlantic Anomaly or, in some reports, the South Atlan. Earlier this year, researchers described how this collapse is centered in a huge expanse of the Southern Hemisphere, stretching from Zimbabwe to Chile, where satellites are more exposed to energetic particles and more prone to glitches. For orbiting hardware, that patch of sky is already a gauntlet.

European spacecraft dedicated to tracking the field, including the trio known as Swarm, have revealed that this weak spot is growing and evolving. Results published in Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors show that while the global field is still robust, the anomaly has deepened and expanded, subjecting satellites to radiation in a more intense way. A separate analysis noted that this mysterious region has grown to nearly half the size of Europe, with According results again tied to Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors and the Swarm mission, underscoring that the anomaly is not a minor blip but a structural feature of the modern field.

How close are we to a full reversal?

One of the most common questions I hear is whether the current weakening means a flip is imminent. Some analyses of the long term trend suggest that, if the present rate of decline continued unchecked, the field’s strength might decay substantially in about 1,300 years, but even that estimate comes with a major caveat: the weakening could slow or stop. A detailed review of variations in Earth’s magnetic field stresses that the position of Earth’s magnetic poles and the strength of the field have changed many times without triggering climate shifts, and that drifting magnetic poles and climate should not be conflated.

Historical records of past reversals show that the last full flip occurred about 78 hundred thousand years ago, and that the intervals between reversals are irregular, which makes predicting the next one inherently uncertain. Environmental scientists in places such as CANADA, FLINTRIDGE, Calif, speaking through outlets like KABC, have emphasized that Earth’s magnetic fields may be changing, but it will not happen overnight, and that any increase in solar radiation at the surface would be modest compared with the extremes that life has already survived.

Impacts on satellites, power grids and aviation

The most immediate vulnerabilities in a weaker field are technological. A growing weak spot in the protective magnetic bubble that surrounds Earth can expose satellites to higher doses of radiation, which in turn can cause malfunctions or outages in everything from weather monitoring to GPS. Engineers already program spacecraft like the Hubble Space Telescope to suspend some operations when they pass through the anomaly, a sign of how seriously operators take the risk. As the weak region grows, more satellites will have to navigate this gauntlet, and shielding and redundancy will become even more critical.

On the ground, the main concern is not people being directly zapped, but the way geomagnetic storms induce currents in long conductors. Analyses of whether geomagnetic pole reversal effects could cause a Worldwide Blackout conclude that while a weaker field would make power lines and pipelines more vulnerable during strong solar events, a global, permanent blackout is unlikely if utilities harden their systems. A related review of what would happen to Humans if the Magnetic Field Flipped notes that for everyday life at the surface, the impacts would be limited, although prudent technological and scientific preparation is essential, a point echoed in coverage of What Would Happen if the field flipped.

Aviation is another sector that will feel the strain. Magnetic compasses and runway designations are tied to the position of the magnetic poles, and as those poles wander, airports periodically have to repaint numbers and update charts. Analysts who have examined how a shift of Earth’s magnetic poles would affect aviation explain that Magnetic Navigation Systems remain fundamental backups even in the age of GPS. They note that magnetic reversals themselves would not instantly ground aircraft, but that increased radiation and more frequent geomagnetic storms could disrupt high frequency radio and the functioning of satellite systems that modern cockpits rely on.

Life, navigation and the long view

Beyond hardware, a changing field affects the animals that use it. During a polar flip, creatures that migrate using the magnetic field to find their way, such as whales, butterflies, sea turtles and birds, could face a confusing and shifting map, a risk highlighted in reporting that notes how these species rely on the field During their journeys. Yet the fossil record does not show mass extinctions neatly aligned with past reversals, and reviews of how the Earth’s Magnetic Field Flip Will Impact Life on Our planet point out that, as How the Earth behaves, even a significantly weakened field is not expected to sterilize the biosphere. Instead, species may adapt through behavioral shifts, redundancy in navigation cues and evolutionary pressure over many generations.

More from Morning Overview