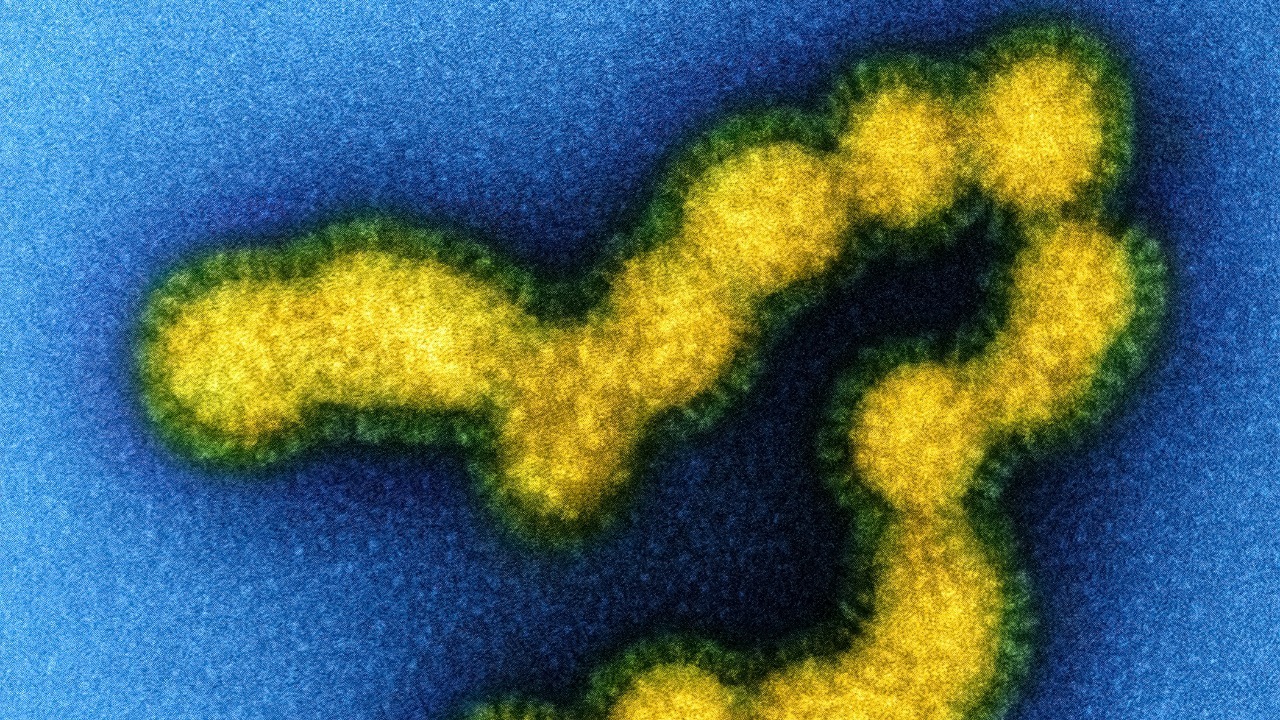

Researchers have uncovered a microscopic weapon that can literally tear viruses apart from the inside, a single protein that turns a cell’s own DNA into a tripwire. Instead of blocking infection at the surface, this system waits until a virus starts to copy itself, then flips a genetic switch that detonates the infected cell and shreds the invader with it. The discovery hints at a new class of antiviral defenses that do not just slow pathogens down but are built to annihilate them.

At the center of the work is a tiny enzyme that behaves like a molecular demolition expert, reconfiguring DNA in response to danger. By tracing how this protein evolved from ancient viral fragments buried in bacterial genomes, scientists are beginning to map a hidden arsenal that microbes have been refining for billions of years. I see that arsenal as a blueprint for future therapies that could one day give human cells the same ruthless ability to sacrifice one to save the many.

The microscopic demolition expert called PinQ

The protein at the heart of this story is an enzyme named PinQ, a compact machine that recognizes when a virus has invaded and then physically rearranges stretches of DNA. Instead of passively waiting for help, PinQ flips specific segments of bacterial DNA when danger appears, turning previously silent genes into an emergency response program. That flip is not symbolic. It is a literal inversion of genetic code that changes which instructions the cell reads, and it happens fast enough to matter in the middle of an active infection.

In practical terms, PinQ acts like a molecular circuit breaker that only trips when viral activity crosses a threshold. The enzyme senses the threat, inverts a defined DNA cassette, and in doing so activates a destructive pathway that can halt viral replication at the cost of the host cell. Researchers traced this behavior to ancient viral fragments embedded in bacterial chromosomes, showing that the same genetic invaders that once threatened these microbes have been repurposed into a defense system. The work on this specialized enzyme, described as a PinQ DNA flipper, underscores how a single protein can decide whether a cell lives or dies when a virus strikes.

How a single protein can blow up an entire virus

What makes PinQ so striking is not just that it kills infected cells, but how it turns that sacrifice into a precise anti-viral strike. When the enzyme flips its target DNA segment, it can activate toxins, membrane pores, or other lethal factors that rupture the cell from within. For a virus that depends on the host’s machinery to copy itself, that sudden collapse is catastrophic. The infected cell becomes a dead end, its contents spilling out in a way that leaves viral particles incomplete or damaged, effectively neutralizing the infection at its source.

This is a classic example of abortive infection, a strategy in which a microbe chooses self-destruction to protect the larger community. In bacterial populations, a single cell armed with PinQ can detect viral replication early, trigger its own demise, and in doing so prevent the virus from reaching neighboring cells. Because the enzyme is wired directly into the genome, the response is hard for viruses to evade without losing their ability to replicate. The result is a system where one protein, by flipping a short stretch of DNA, can set off a chain of events that leaves an entire viral lineage stranded and unable to spread.

Ancient viral fragments turned into a defense system

The origin story of PinQ is as important as its function. The enzyme is not an isolated invention, it is part of a broader pattern in which bacteria have captured fragments of viral DNA and stitched them into their own chromosomes. Over evolutionary time, those fragments have been reshaped into regulatory switches and defense modules, turning yesterday’s invaders into today’s security infrastructure. PinQ sits at the center of one such module, using its ability to recognize and invert specific DNA sequences that were once part of viral genomes.

That history matters because it shows how deeply intertwined viruses and their hosts have become. Instead of simply deleting viral remnants, bacteria have treated them as raw material, refining them into tools that can sense infection and respond with lethal precision. The PinQ system is a vivid example of this recycling, where ancient viral fragments buried in bacterial DNA now help trigger a controlled explosion that stops new viruses in their tracks. It suggests that many other proteins with similar origins are still waiting to be discovered, each potentially offering a different way to sabotage viral replication.

From bacterial warfare to human medicine

The leap from a bacterial enzyme to a human therapy is not straightforward, but the conceptual payoff is enormous. PinQ shows that it is possible to encode a self-destruct circuit directly into the genome, one that activates only when a specific pattern of viral activity is detected. In principle, a similar logic could be engineered into human cells, especially in tissues that are frequent viral targets, such as the respiratory tract or the liver. Instead of relying solely on antibodies or small-molecule drugs, clinicians could one day deploy genetic circuits that sense viral replication and trigger a controlled shutdown of infected cells before the pathogen gains a foothold.

There are obvious risks in giving human cells the power to kill themselves more readily, from unintended activation to long-term effects on tissue health. Yet the bacterial precedent is compelling. Microbes have been running these high-stakes calculations for billions of years, balancing individual loss against population survival. By studying systems like PinQ in detail, from the exact DNA sequences it flips to the downstream toxins it activates, researchers can begin to design safer, more targeted versions for therapeutic use. The same principles could also inform antiviral strategies in agriculture, where engineered self-sacrifice in crops or livestock cells might contain outbreaks before they spread through entire herds or fields.

The next frontier in programmable immunity

PinQ is part of a broader shift in how scientists think about immunity, away from static barriers and toward programmable, information-driven defenses. Just as CRISPR turned a bacterial memory of past infections into a genome editing tool, enzymes like PinQ reveal that cells can carry embedded logic circuits that respond to very specific molecular cues. I see this as the early stage of a new discipline in which immunity is not just boosted or suppressed, but rewritten at the level of genetic code to follow rules we design.

In that future, a “tiny protein that can blow up entire viruses” is less a curiosity and more a template. By cataloging the full range of DNA flipping enzymes, toxin modules, and viral sensing elements that bacteria already use, researchers can assemble modular systems that detect particular pathogens and respond with calibrated force. Some circuits might trigger cell death, others might release antiviral peptides or signal neighboring cells to enter a protective state. The discovery of PinQ and its ancient viral roots is a reminder that nature has already solved many of the problems modern medicine is struggling with. The challenge now is to read those solutions correctly, then translate them into therapies that can protect human communities as effectively as they protect a bacterial colony.

More from Morning Overview