For decades, scientists have known that a misbehaving protein sits at the heart of Parkinson’s disease, yet the precise chain of events that turns that protein into brain cell death has remained frustratingly vague. Now, a series of converging studies is filling in that gap, tracing a direct molecular route from the Parkinson’s protein to the tiny power stations inside neurons that ultimately fail. The emerging picture is not just a mechanistic curiosity, it is already pointing toward drug targets that could keep vulnerable brain cells alive for far longer.

At the center of this story is a destructive partnership between a Parkinson’s linked protein and the mitochondria that keep neurons supplied with energy. By mapping how that interaction unfolds, researchers are beginning to explain why dopamine producing cells in particular are so fragile, and how carefully designed molecules might interrupt the damage before symptoms ever surface.

The toxic handshake between Parkinson’s protein and mitochondria

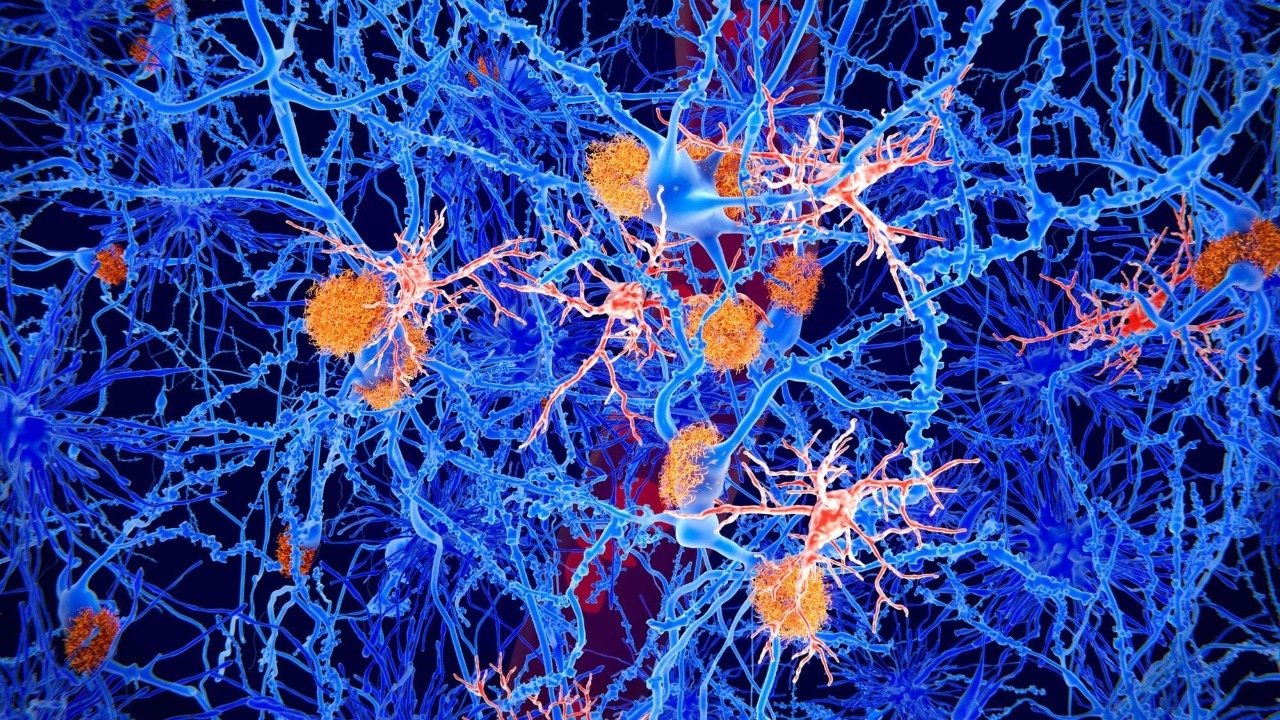

The new work identifies a direct molecular collision between a protein associated with Parkinson’s and the machinery that maintains mitochondria, the organelles that generate the energy neurons need to fire. In laboratory models, researchers watched as the Parkinson’s related protein bound to components that normally help keep mitochondrial proteins in good repair. Those two malfunctions, protein clumping and mitochondrial failure, had been linked before, but the experiments now show how one feeds the other inside living cells.

Scientists describe this as a harmful interaction that sabotages the brain’s “cellular powerhouses,” a phrase that captures how central mitochondria are to neuron survival. By tracing the contact between the Parkinson’s protein and mitochondrial quality control factors, including the protease systems that clear out damaged components, the team could see energy production falter and oxidative stress rise. In effect, the protein acts like a wrench thrown into the gears of the mitochondrial maintenance system, a mechanism that earlier work had only inferred indirectly but that is now mapped in detail in lab tests.

From molecular damage to dying neurons

Once that toxic handshake occurs, the consequences ripple outward through the neuron. The damaged mitochondria cannot keep up with the intense energy demands of brain cells that fire constantly, especially the dopamine neurons that degenerate in Parkinson’s. In cell and animal models, scientists saw that the interaction between the Parkinson’s protein and mitochondrial proteases led to a buildup of defective proteins, swelling and fragmentation of mitochondria, and eventually the activation of cell death pathways that mirror what pathologists see in human brains with the disease. The cascade is described in detail in work highlighted by David Nield, who notes that the neurons lose the energy they need to work effectively long before they finally die.

What makes this link so important is that it connects two hallmarks of Parkinson’s that had often been studied in isolation. Protein aggregates in the form of Lewy bodies and mitochondrial dysfunction have each been proposed as root causes, but the new data show that they are intertwined steps in a single process. By following the damage from the initial protein interaction through to the loss of dopamine neurons, the investigators provide a coherent explanation for how early molecular missteps translate into the tremors, stiffness, and slowed movement that define the condition, a narrative reinforced in further reporting on interconnected neuronal damage.

Scientists map the “missing link” in Parkinson’s brain damage

To pin down this chain of events, scientists combined structural biology, cell imaging, and disease models to show a direct molecular link between a Parkinson’s related protein and failing mitochondria. In carefully controlled experiments, scientists showed that when the Parkinson’s protein binds to mitochondrial quality control components, it triggers a wave of damage in Parkinson’s disease models. The same work, described as identifying the “missing link” driving Parkinson’s brain damage, connects molecular snapshots with functional readouts of mitochondrial collapse.

The mechanistic picture is sharpened further in analyses that emphasize how this interaction undermines the cell’s ability to clear misfolded proteins. By interfering with mitochondrial proteases and chaperones, the Parkinson’s protein effectively disables the clean up crew that would normally prevent toxic buildup. That insight is echoed in additional coverage of how a direct molecular link between a Parkinson related protein and mitochondrial failure drives damage in disease models, giving researchers a concrete target to measure as they test potential therapies.

Turning mechanistic insight into drug targets

Once a pathway is mapped, the obvious next question is whether it can be interrupted. Earlier this year, researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine reported a potential new target that could help treat Parkinson’s by restoring healthier brain function. Their work, described as a breakthrough, focuses on modulating protein damage responses in the brain, an approach that dovetails with the new understanding of how mitochondrial quality control is derailed. By aiming at the machinery that responds to misfolded proteins, rather than the aggregates themselves, they hope to preserve neuronal health even in the presence of genetic risk factors.

In parallel, another team has shown that it is possible to restore brain cell function in Parkinson’s models by correcting protein damage and mitochondrial stress. After three years of study, the group behind Researchers Restore Brain in Parkinson models reported that targeting the root cause of protein damage in the brain could reverse some of the functional deficits. Their closer look at protein damage suggests that if the harmful interaction between the Parkinson’s protein and mitochondrial proteases can be blocked, neurons may regain enough energy capacity to resume more normal signaling.

A broader race to decode Parkinson’s origins

The new mechanistic work does not exist in isolation, it is part of a broader race to understand where Parkinson’s begins and how early interventions might work. A groundbreaking study from Wuhan University has been described as turning long held assumptions about Parkinson’s upside down, with researchers there probing mysterious origins that may lie outside the traditional focus on the brain. That work, which has been amplified by collaborators at Case Western Reserve, feeds into an ambitious goal of moving disease modifying treatments into clinical trials within the next five years, a timeline that reflects growing confidence that the field is finally closing in on the root biology.

At the same time, teams at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine are refining specific therapeutic strategies that build on the new mechanistic insights. Their report that Researchers have discovered a potential new target to treat Parkinson’s disease, framed explicitly as a breakthrough, underscores how quickly basic biology is being translated into drug discovery. Social media updates highlighting how Researchers at Case are closing in on the disease’s origins reinforce the sense that the field is moving from descriptive pathology to actionable mechanisms.

More from Morning Overview