Conservation has long focused on saving charismatic animals and sweeping landscapes, yet some of the most consequential life forms on Earth are invisible to the naked eye. As climate stress, habitat loss, and pollution accelerate, the case for protecting microbial life is shifting from niche curiosity to central strategy, with microbes emerging as quiet powerhouses that stabilize ecosystems, store carbon, and even keep endangered species alive. If conservation is judged by impact per dollar and per square meter, safeguarding microbial diversity may be the most transformative win available.

I see a growing body of research converging on a simple but radical idea: protecting microbes is not a side project, it is the scaffolding that makes other conservation work possible. From soil bacteria that feed forests to gut microbes that determine whether a rare animal survives reintroduction, the smallest organisms are increasingly shaping the biggest decisions in environmental policy and wildlife management.

Why microbes are the hidden backbone of biodiversity

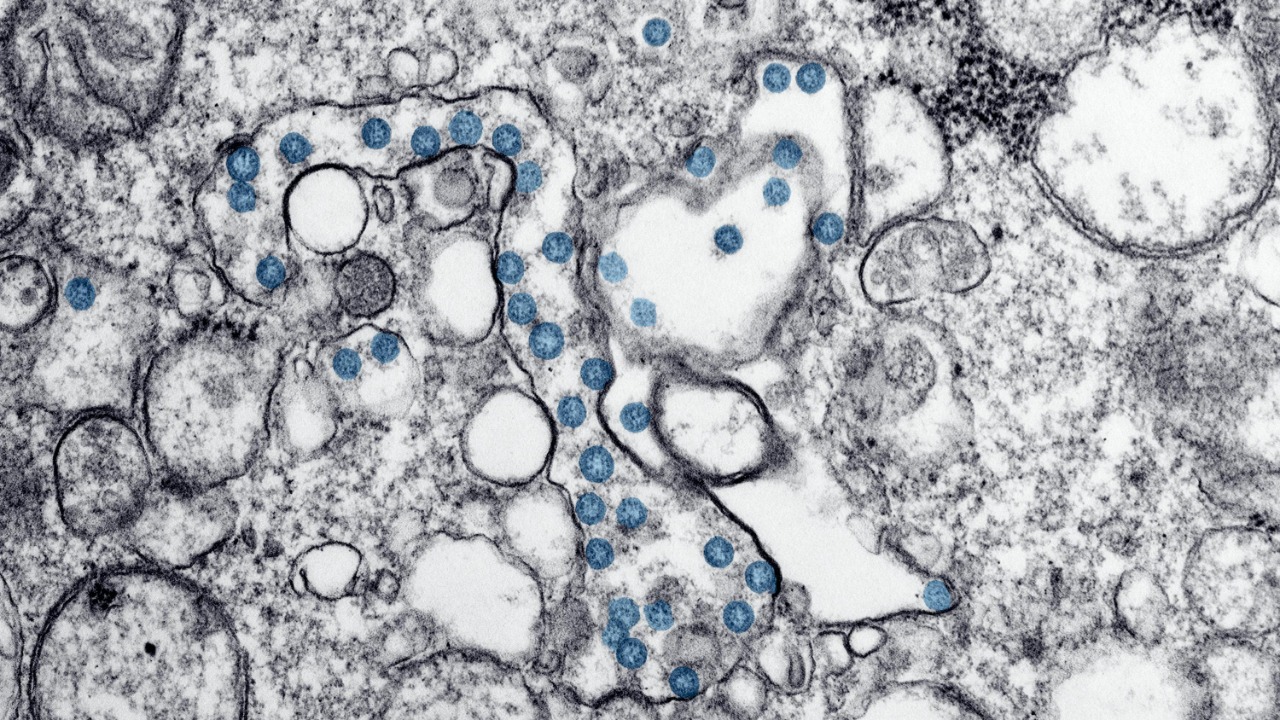

Microbes underpin nearly every ecological process that conservationists care about, from nutrient cycling to disease resistance, yet they rarely appear in protected area plans or species recovery targets. The organisms that fix nitrogen in soils, decompose organic matter, and regulate greenhouse gases are overwhelmingly microbial, and their collective biomass and genetic diversity dwarf that of plants and animals. When these microscopic communities are disrupted, entire food webs can unravel, even if the larger species appear intact for a time.

Recent work on microbial ecology has emphasized that bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses form intricate networks that respond rapidly to environmental change, often serving as early warning systems for ecosystem collapse. Studies of soil and aquatic microbiomes show that shifts in microbial composition can precede visible declines in plant cover or animal populations, which means that monitoring microbes can give managers a head start on intervention. As researchers refine tools to track these communities at scale, they are building a case that microbial conservation is not a luxury but a prerequisite for resilient landscapes, a point underscored by emerging syntheses of microbial biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Endangered species depend on endangered microbes

For many threatened animals and plants, survival hinges on intimate partnerships with specific microbes that help them digest food, fend off pathogens, or tolerate heat and drought. Conservation biologists are documenting cases in which reintroduction programs fail not because the habitat is unsuitable, but because the animals are released without the microbial allies they evolved with. Gut bacteria, skin microbiomes, and root-associated fungi can act as invisible life support systems, and when those systems are missing or altered, mortality rates climb and reproduction falters.

Reporting on endangered wildlife has highlighted how microbiome transplants and probiotic treatments are becoming part of standard conservation toolkits, from amphibians battling fungal disease to mammals struggling with novel diets in fragmented habitats. In some projects, scientists now bank microbial samples alongside sperm, eggs, and seeds, treating them as co-endangered lineages that must be preserved together. The growing recognition that species recovery plans must include microbial partners is reflected in detailed accounts of how bacteria and conservation intersect in field programs and captive breeding facilities.

From seed banks to microbe vaults: a new conservation infrastructure

Traditional conservation infrastructure, such as seed banks and frozen zoos, is beginning to expand into dedicated repositories for microbial life. Researchers are building cryogenic libraries of soil microbes, gut communities, and symbiotic bacteria that can be revived to restore degraded habitats or support struggling species. These efforts mirror the logic of seed banking, but they operate at a far finer scale, capturing not just individual species but entire community assemblages that can be reintroduced as living consortia.

Coverage of these initiatives has described how laboratories and conservation centers are experimenting with protocols to freeze, catalog, and later reconstitute complex microbiomes without losing key functional traits. Some projects focus on preserving microbes from extreme environments that may hold clues to climate resilience, while others target the microbiota of rare animals before their populations decline further. The technical and ethical debates around what to store, how to prioritize, and who controls access to these microbial archives are beginning to resemble earlier arguments over genetic resource banking, as seen in recent reporting on microbial preservation and its role in future conservation planning.

Soil, food, and the microbial roots of sustainable agriculture

Microbial conservation is not confined to wild landscapes; it is also reshaping how farmers think about soil health and crop resilience. The bacteria and fungi that live around plant roots influence nutrient uptake, water retention, and resistance to pests, which means that protecting these communities can reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. As regenerative agriculture gains traction, more producers are treating soil microbiomes as assets to be nurtured rather than invisible background noise.

Even at the scale of a small farm, the link between microbial life and human diets is becoming more visible. Growers who specialize in nutrient-dense crops, such as microgreens, often credit their success to careful management of living soils and composts that support diverse microbial communities. Customer enthusiasm for intensely flavored, fast-growing greens is tied to how these plants interact with their microbial environment, a relationship that some producers highlight when explaining why customers love microgreens and other soil-grown specialty crops. Protecting the microbes that make these systems productive is, in effect, a form of everyday conservation that links biodiversity to food security.

Modeling invisible worlds: digital tools for microbial conservation

Because microbes are hard to see and track, conservationists are turning to digital tools and simulation platforms to map where microbial diversity is most at risk and which interventions might work. Spatial modeling techniques originally developed for gaming and robotics are being repurposed to explore complex environments, allowing researchers to test how microbial communities might respond to changes in land use, temperature, or pollution before they commit to field experiments. These virtual explorations help identify priority zones for sampling and protection, especially in remote or sensitive habitats.

Some of the same logic that guides players through custom digital maps is now guiding scientists through microbial landscapes, as they design virtual scenarios to probe how communities assemble and collapse. Tutorials that explain how to create a custom match for exploring a map in a tactical game, for example, mirror the stepwise thinking behind ecological simulations that adjust variables and observe outcomes, a parallel that becomes clear when examining tools for exploring a map and translating that mindset to environmental modeling. As these methods mature, they promise to make microbial conservation more predictive and less reactive, turning invisible processes into navigable data.

Education, ethics, and the politics of tiny life

For microbial conservation to move from specialist circles into mainstream policy, education systems will need to treat microbes as central actors in environmental stories rather than as footnotes in biology textbooks. Curriculum designers are beginning to integrate microbiome science into lessons on climate, agriculture, and public health, framing microbes as both potential threats and essential partners. Detailed teaching resources on ecology and sustainability now include sections on microbial processes, helping students connect everyday experiences, such as composting or fermentation, to global cycles of carbon and nitrogen.

These shifts are visible in educational materials that encourage inquiry-based learning around environmental systems, where students analyze data, debate trade-offs, and design their own conservation strategies. Some resources explicitly link microbial topics to broader questions of justice and governance, asking who benefits when certain microbial communities are protected or exploited. A comprehensive teaching guide on environmental education, for instance, outlines how to weave microbiology into project-based units on land use and climate resilience, illustrating how curriculum frameworks can elevate microbes from background characters to central subjects of civic debate.

Robots, AI, and the next frontier of microbial fieldwork

As conservationists push into harsher and more remote environments to sample microbial life, they are increasingly relying on robots and autonomous systems to do work that would be too dangerous or time consuming for human teams. Legged robots, underwater vehicles, and aerial drones can carry sensors and samplers into caves, deep oceans, and polar ice, collecting microbial data at scales that were previously impossible. These machines are not replacing field biologists, but they are extending their reach and allowing more systematic surveys of microbial diversity across challenging terrain.

Technical reports on mobile robots describe how platforms equipped with environmental sensors can map temperature, humidity, and chemical gradients while also gathering biological samples, creating rich datasets for microbiologists. One recent conference manuscript details how a quadruped robot navigated uneven ground to support environmental monitoring, illustrating how robotic field systems can be adapted for microbial sampling in fragile habitats where human footprints would be too disruptive. As these tools become more affordable and robust, they are likely to become standard equipment in microbial conservation campaigns.

AI benchmarks, policy frameworks, and the governance of microbial data

The explosion of microbial data from sequencing, sensors, and robotic surveys is colliding with advances in artificial intelligence, creating new opportunities and new governance challenges. AI models can sift through vast genomic datasets to identify patterns, predict functions, and flag unusual communities that might warrant protection. At the same time, the reliability of these models depends on rigorous evaluation, which has led researchers to develop specialized benchmarks that test how well different systems handle complex scientific information.

One such benchmark effort, documented in a technical diff of evaluation results for large language models, shows how teams compare model performance across tasks and versions, including scientific reasoning and data interpretation. The detailed scoring of systems like Nous-Hermes-2-Mixtral-8x7B-DPO in a structured evaluation underscores how AI benchmarks are becoming part of the scientific infrastructure that will shape how microbial data are analyzed and trusted. Alongside these technical tools, legal scholars and policymakers are grappling with questions about ownership, access, and benefit sharing for microbial genetic resources, debates that are captured in detailed analyses of biodiversity governance and digital sequence information.

Microbial conservation as climate strategy

Microbes are central players in the global carbon cycle, mediating processes that determine how much carbon stays locked in soils and oceans versus how much escapes into the atmosphere. Protecting and restoring microbial communities that enhance carbon storage, such as those in peatlands, seagrass meadows, and healthy agricultural soils, can amplify the impact of climate mitigation efforts. Conversely, disturbances that disrupt these communities can accelerate greenhouse gas emissions, turning once-stable carbon sinks into sources.

Recent experimental work has begun to quantify how shifts in microbial composition under warming scenarios affect rates of decomposition and methane production, with some studies suggesting that targeted management of microbial communities could slow feedback loops that intensify climate change. Reports on controlled trials and field observations, including new findings summarized in a release on microbial climate responses, highlight both the promise and the complexity of using microbes as levers in climate policy. Integrating these insights into national climate plans will require closer collaboration between microbiologists, modelers, and policymakers, but the potential payoff is significant: a climate strategy that works with the planet’s smallest engineers instead of ignoring them.

More from MorningOverview