Russian state media has been promoting a new generation of “super torpedoes” that, in theory, could trigger massive waves against coastal cities and reshape the nuclear balance. The rhetoric is designed to sound apocalyptic, but it also raises a practical question for Americans: how much of this is real military capability and how much is psychological warfare aimed at the United States and its allies?

I want to unpack what is actually known about these nuclear-powered torpedoes, how they might work, and what independent experts say about their ability to generate tsunamis or wipe out ports. The picture that emerges is less about a single doomsday weapon and more about a broader contest of messaging, deterrence and vulnerability along the world’s coastlines.

What Russia claims its “super torpedo” can do

Moscow’s messaging around its nuclear-powered Poseidon torpedo has leaned heavily on spectacle, with officials and propagandists describing a weapon that could slip across oceans and unleash towering waves against enemy shores. In Russian television segments and online clips, the device is often framed as a kind of underwater doomsday machine, capable of contaminating vast stretches of coastline and rendering major ports unusable. That narrative is meant to convey that even heavily defended countries like the United States cannot count on missile shields or early warning systems to keep their cities safe.

Russian outlets have repeatedly highlighted the idea that a single Poseidon could devastate a coastal metropolis, and that the Kremlin ultimately wants a fleet of these torpedoes deployed on specialized submarines. Independent nuclear analysts have noted that one nuclear-armed Poseidon, if it performed as advertised, could indeed decimate a coastal city and that Russian plans envision as many as 30 of them in service. In Russian domestic politics, that kind of imagery reinforces the message that the country has a unique answer to Western missile defenses and can still threaten the American homeland even if traditional delivery systems are constrained.

How the torpedo is supposed to work under the sea

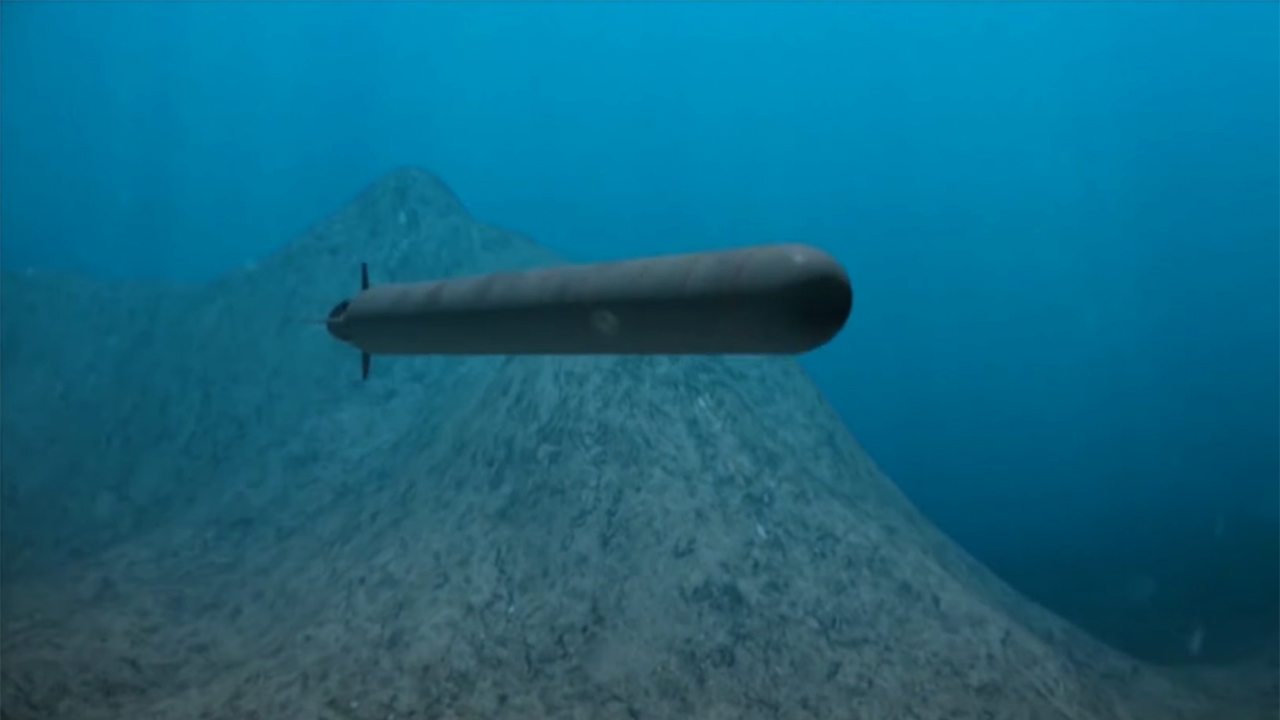

At the core of the Poseidon concept is a long-range, nuclear-powered torpedo that can travel autonomously for thousands of kilometers at great depth. In theory, a compact reactor would give the weapon almost unlimited range, allowing it to be launched from Russian waters and then navigate around undersea terrain and patrol patterns to approach a target coast. The design is meant to bypass radar and missile defense networks that focus on the air and space domains, exploiting the relative opacity of the deep ocean.

Russian state-linked channels have circulated animations and short clips that show the torpedo cruising silently through dark water before detonating near an enemy shoreline. One widely shared video, promoted on social platforms, depicts a Poseidon-like device generating a towering wall of water aimed at a Western city, imagery that has been echoed in posts such as an animated underwater strike shared on Instagram. The technical details behind those visuals remain classified and unverified based on available sources, but the consistent theme is that the weapon would operate below the reach of most current surveillance systems until the moment of detonation.

Could a nuclear torpedo really trigger a tsunami?

The most dramatic claim attached to Poseidon is that it could generate an artificial tsunami, a wave so large that it would sweep inland and obliterate coastal infrastructure. Physically, a nuclear explosion underwater does displace enormous volumes of water and can create powerful waves, but whether that translates into a true tsunami depends on depth, yield and geography. Natural tsunamis are driven by the movement of entire sections of the seafloor, not just a single point blast, which is why many scientists are skeptical of the more extreme Russian rhetoric.

Specialists in nuclear effects have pointed out that while a very large underwater detonation could severely damage a harbor and nearby coastline, scaling that up to a region-wide tsunami is far more difficult than propaganda videos suggest. Some of the most alarmist scenarios circulating on social media, including posts that describe radioactive waves inundating whole countries, are not backed by open technical assessments and remain unverified based on available sources. A short clip shared on X, for example, amplified the idea of a “radioactive tsunami” without providing underlying data, even as it echoed Russian talking points about a coastal wave weapon. The gap between cinematic imagery and peer-reviewed modeling is one of the reasons many Western experts treat the tsunami framing as psychological pressure rather than a precise description of battlefield effects.

What independent experts say about the real damage potential

Stripped of the tsunami branding, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed torpedo still represents a serious threat to any coastal nation. Analysts who have studied the Poseidon concept argue that even a single detonation near a major port could destroy critical infrastructure, sink ships in harbor and contaminate surrounding waters, with long-term economic and environmental consequences. The fact that Russian planning documents reportedly envision multiple such weapons, potentially carried by dedicated submarines, underscores that this is not just a one-off experiment but part of a broader strategic toolkit.

Technical assessments emphasize that the most credible danger lies in targeted port destruction and coastal contamination rather than continent-spanning waves. A detailed examination of the system’s potential effects concluded that one Poseidon could effectively wipe out a large coastal city if detonated at the right depth and distance, and that Russian planners have spoken of deploying around 30 of these torpedoes to ensure redundancy and survivability, as reflected in the analysis of a nuclear-armed underwater drone. That kind of arsenal would complicate any U.S. or NATO effort to protect key naval hubs, energy terminals and logistics nodes, even if the more spectacular tsunami scenarios never materialize.

How U.S. coastal cities and bases factor into the risk

For the United States, the most immediate vulnerability is not a Hollywood-style wave crashing into Manhattan, but the concentration of military and economic assets along the coasts. Major naval bases, including those in Norfolk, San Diego and Pearl Harbor, sit within relatively confined harbors where an underwater detonation could be particularly devastating. Critical civilian infrastructure, from liquefied natural gas terminals to container ports, also clusters near shorelines, creating tempting targets for any adversary that can deliver a warhead underwater.

American officials and allied governments have long recognized that their coastal cities are exposed to sea-based threats, which is why anti-submarine warfare and undersea surveillance remain core missions for the U.S. Navy and NATO. European governments, for example, have repeatedly raised concerns about Russian submarine activity in the North Atlantic and around undersea cables, a pattern that has been documented in reporting on Russian naval operations. In that context, Poseidon is less a standalone superweapon than another layer in a broader undersea competition that already forces Washington and its partners to invest heavily in sensors, patrol aircraft and quiet submarines.

Propaganda, signaling and the psychology of “doomsday” weapons

Russia’s public handling of Poseidon has been as much about messaging as about hardware. By showcasing animations of coastal destruction and talking up radioactive waves, the Kremlin is signaling that it has novel ways to threaten the American homeland even if traditional nuclear delivery systems are constrained by treaties or missile defenses. That kind of signaling is aimed at multiple audiences at once: domestic viewers who are told their country possesses unique superweapons, Western policymakers who are reminded of their own vulnerabilities, and non-aligned states that may see Russia as a technological equal to the United States.

The information environment around these weapons is noisy, with state television segments, social media posts and short video packages all reinforcing the same themes. A recent video report, for instance, highlighted Russian undersea capabilities and framed them as a response to Western pressure, using dramatic visuals of submarines and underwater launches to underscore the point, as seen in a broadcast segment shared with international audiences. In my view, that layering of traditional and digital propaganda is part of the weapon’s design: the psychological effect of a supposed unstoppable torpedo is meant to travel farther and faster than the torpedo itself ever could.

What history and strategy tell me about the real stakes

When I look at Poseidon in the broader arc of nuclear history, it fits a familiar pattern in which new delivery systems are introduced to bypass perceived vulnerabilities. During the Cold War, both superpowers experimented with exotic concepts, from fractional orbital bombardment systems to nuclear depth charges, in an effort to ensure that no adversary could ever feel fully protected. The underwater drone concept updates that logic for an era in which missile defenses and precision strike capabilities have raised doubts in Moscow about the survivability of its traditional arsenal.

Strategically, the United States has to treat any credible nuclear delivery system as a serious issue, but it also has to avoid letting the most theatrical claims drive policy. That means focusing on practical steps like improving undersea surveillance, hardening key ports and refining escalation management, rather than reacting to every new animation or social media post. It also means parsing Russian statements with the same care that cryptanalysts apply to complex texts, a mindset reflected in the way defense analysts sometimes lean on large linguistic datasets such as an English top words corpus or comprehensive wordlists like the Princeton autocomplete file and the Delaware dictionary list when building tools to sift propaganda from genuine doctrinal shifts. In the same way that cybersecurity experts use password-strength meters such as the zxcvbn algorithm to gauge risk, nuclear planners must continuously test whether new Russian systems actually change the strategic balance or simply repackage old threats in more frightening language.

More from MorningOverview