Robots have never looked more impressive, yet in the real world they still fail at the basic promise of doing useful work without constant human babysitting. Slick demo clips and viral humanoid stunts hide a stubborn truth: outside tightly controlled environments, most machines wobble, stall, or simply give up. The gap between the fantasy of tireless metal helpers and the reality of fragile prototypes is exactly where they still, in practical terms, completely suck.

That failure is not for lack of money, talent, or hype. It is rooted in hard technical limits, from clumsy hardware and weak power systems to brittle artificial intelligence that cannot cope with messy homes or unpredictable streets. When I look past the marketing, the pattern that emerges from labs, factories, and living rooms is consistent: robots shine in narrow, repetitive niches and fall apart as soon as life gets even slightly weird.

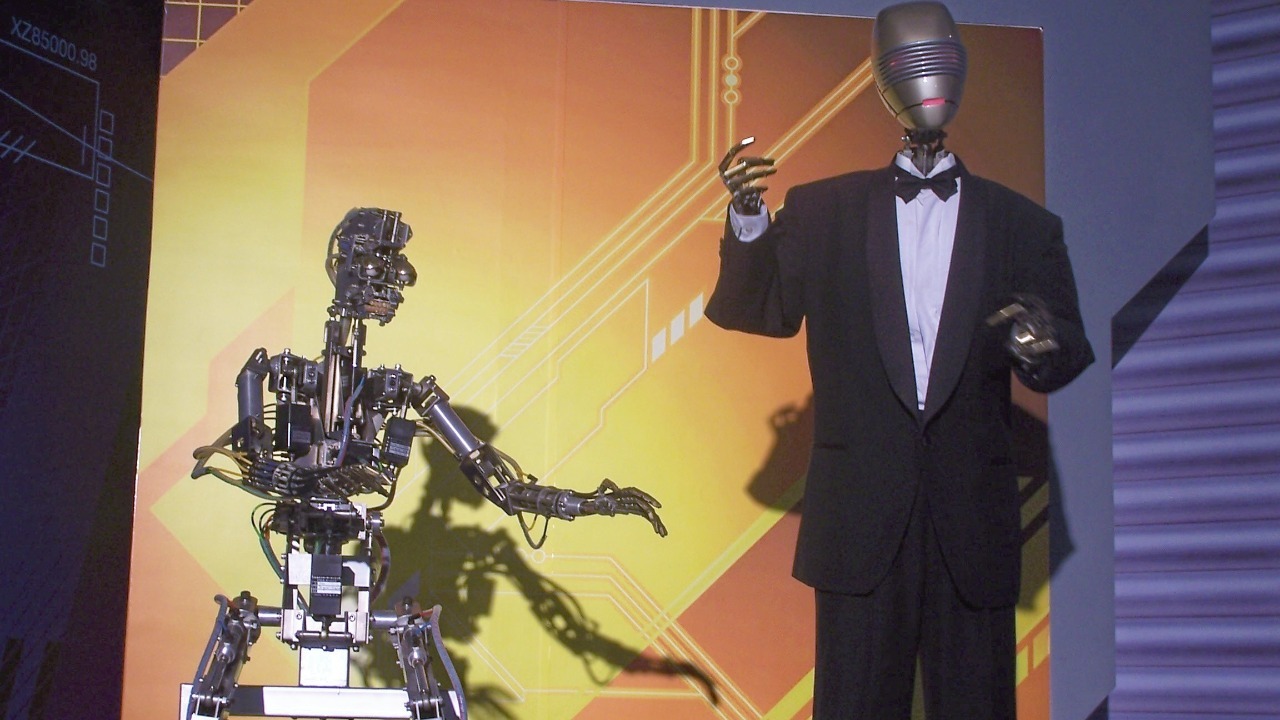

Humanoid hype versus fragile reality

Humanoid robots have become the industry’s favorite symbol of progress, yet the people building them are increasingly candid about how unreliable they still are. Developers talk about machines that can barely keep their balance, let alone handle a crowded warehouse or a cluttered kitchen, and even a polished viral clip can hide how often a biped falls or freezes between takes. One report describes a Post that was so awkward it had to be deleted, a reminder that behind every triumphant montage is a lot of falling over and emergency stops.

Even when the hardware stays upright, the intelligence inside the shell is far narrower than the humanoid form suggests. A detailed look at current projects in Future Society research shows that even advanced platforms marketed under banners like Advanced Transport or Artificial Intelligence are usually tuned for a single choreographed task. The same analysis notes that categories such as Health, Medicine, Robots and Machines, and Science and Energy are full of prototypes that work only under lab conditions, which is a long way from the general-purpose helper implied by the humanoid silhouette.

Home robots that move slowly and break easily

Nowhere is the disappointment more obvious than in the home, where buyers are promised robotic helpers and receive expensive novelties. A widely shared early trial of a domestic machine showed that loading just three items into a dishwasher took about five minutes and that grabbing a bottle of water from a fridge was a minor saga of misgrips and re-tries, as seen in a Nov demo. A longer version of the same test on another channel shows the same system creeping around a kitchen, taking so long to complete basic chores that any human could have finished the job several times over.

Industry analysts argue that the problem is not a lack of demand but the brutal complexity of real homes, where every counter, cupboard, and cereal box is slightly different. One assessment of Home robots notes that their unfulfilled potential stems from this variability, not from lazy manufacturers or uninterested consumers. A separate breakdown of why Home robots still disappoint points to the same bottleneck: perception and manipulation systems that crumble as soon as they leave the tidy, pre-mapped demo apartment.

Motors, power, and the physics that refuse to cooperate

Under the glossy shells, most humanoids still rely on electric motors and gearboxes that were never designed to mimic human muscles. One detailed community critique argues that Currently the vast majority of companies are diving into humanoid designs with electric motors even though these actuators struggle to reproduce the smooth, compliant motion of biological joints. The same discussion describes motor-based robotics as a dead end for lifelike movement, because the hardware is either too stiff to be safe around people or too weak to handle real loads.

Power systems are an equally stubborn constraint. Medical analysts describe Power and Energy as one of the biggest problems for robots, noting that Power and energy are big problems for robots because They need good power sources to work right. The same overview points out that Battery Li technologies still struggle to deliver long runtimes without adding so much weight that the machine becomes slow, dangerous, or both, which is why many impressive prototypes are tethered to cables or limited to short, carefully timed demos.

Brains that ace language but fail at dishes

Artificial intelligence has made robots sound smarter, but it has not made them much better at picking up socks or sorting groceries. A detailed explanation of Moravec theory notes that Austrian scientist Hans Moravec described how computers find abstract reasoning easier than intuitive sensorimotor skills, which is why a chatbot can debate philosophy while a robot still struggles with a doorknob. That paradox shows up every time a machine can plan a route in software but cannot cope with a slightly moved chair in the hallway.

Engineers are now putting large language models into robot bodies in the hope that better reasoning will translate into better behavior. One research group describes how a system specifies everything that is possible or not possible in the environment and then refines its actions through many cycles of trial and error and thousands of simulated experiences, as detailed in a Mar study. Even so, the same work concedes that Even after all that training, the robot still needs a tightly defined environment to make daily life easier, which is a polite way of saying it breaks down as soon as reality drifts from the script.

Practitioners on the ground are blunt about the limits of this approach. One robotics engineer notes that tasks like general command recognition, manipulation of highly deformable and varying objects, and bipedal locomotion will likely require hybrid approaches for a long time, as discussed in an Oct discussion. A second comment in the same thread, introduced with the word But, underlines that clever neural networks alone will not fix the messy physics of deformable laundry or sloshing liquids, which is why so many AI-powered robots still look lost in ordinary kitchens.

Stage-managed demos and narrow real-world wins

The gulf between marketing and reality is perhaps clearest in high-profile corporate showcases. Analysts reviewing one flagship humanoid project concluded that Tesla robots on stage were just remotely controlled dummies, not autonomous workers. That finding, echoed in a follow up that states that Tesla’s robots were teleoperated, undercuts the idea that these machines are ready to walk into factories and replace human staff.

Yet it would be wrong to say robots fail everywhere. Agricultural systems like Aggeris, a spinout from the University of Sydney, already move over crops to detect and pick weeds without human guidance, and a later profile of University of Sydney work notes that such field robots thrive in constrained, repetitive tasks. A broader survey of industrial and social machines in categories like Robots and Machines shows the same pattern: tightly scoped jobs in Advanced Transport or Health and Medicine succeed, while general household help still lags.

Experts who track the sector argue that until we solve core issues like robust autonomy, safe actuation, and reliable power, robots will remain stuck in this awkward adolescence. One technical overview on What the current limitations are notes that Until we come up with better power sources and more reliable sensing, robots will struggle with any kind of serious autonomous work. A separate medical risk assessment on Power and safety warns that One big problem with robots is the potential for job losses by 2030 because of automation, even as it concedes that today’s machines are still limited by the same Battery Li and control issues that make them clumsy in everyday life.

More from Morning Overview