Plasma technology is moving from science fiction concept to practical hardware, promising to reshape how spacecraft are tested, powered, and protected. In labs from Colorado to Moscow, engineers are learning to tame superheated, electrically charged gas and use it both as a brutal testing environment and as a remarkably efficient rocket exhaust. If these efforts pay off, the same physics that once doomed a shuttle could underpin a new era of safer reentry and radically faster trips to Mars.

At the heart of this shift is a new generation of “plasma tunnels” and plasma engines that let researchers recreate the violence of hypersonic flight on the ground and then harness similar conditions in space. I see a feedback loop emerging: better ground facilities make it possible to design bolder spacecraft, while advances in propulsion raise the stakes for testing, because vehicles will fly hotter, faster, and farther than anything built before.

From shuttle tragedy to purple-glow plasma tunnels

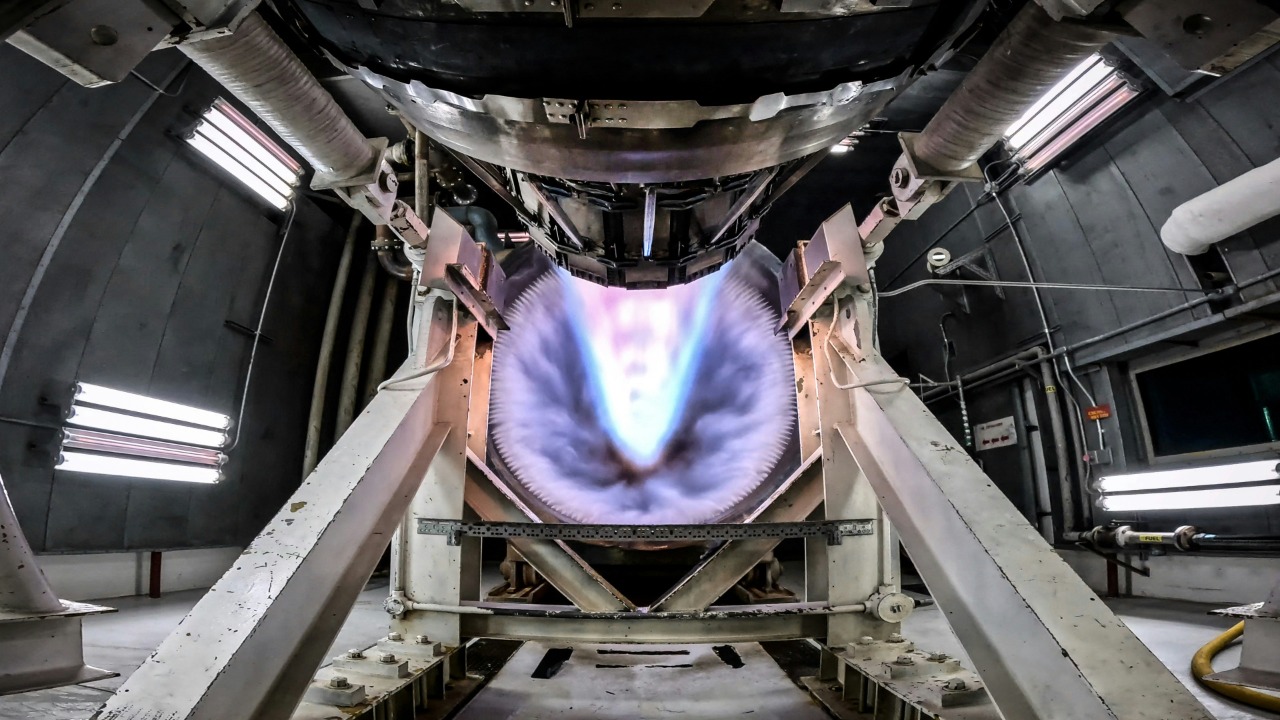

The Columbia disaster exposed how little margin for error exists when a vehicle slams into the atmosphere at hypersonic speed, and it pushed researchers to find ways to reproduce those extreme conditions without risking lives. At the University of Colorado Boulder, engineers have built a one-of-a-kind facility that uses a powerful electrical discharge to turn gas into a searing plasma stream, then drive it over test materials at hypersonic-like conditions inside a compact plasma tunnel. Instead of relying only on computer models, they can now watch real hardware erode, crack, or survive in a controlled environment that mimics the upper atmosphere.

Inside that chamber, the researchers hit their plasma with such intense energy that the gas glows purple and reaches temperatures comparable to those on a returning spacecraft, creating a miniature storm of ionized particles around test samples. By adjusting the flow and power, the team can explore how different shapes and materials behave once a vehicle hits those hypersonic regimes, work that is especially urgent if space tourism is going to send more people to orbit safely and effectively. The same setup lets them probe how radio signals might cut out or how control surfaces respond when wrapped in a sheath of glowing plasma, a problem that has haunted hypersonic flight for decades.

Scaling up: global race for hotter, smarter test facilities

Colorado is not alone in betting that better ground testing will unlock safer high-speed travel. In Illinois, a new research facility houses what is described as the largest plasma wind tunnel in its class, a unique experimental setup that lets engineers blast ultra high temperature ceramic samples with a focused plasma stream. The Plasmatron X facility, led by researcher Elliott, is designed to expose materials to the kind of thermal and chemical abuse they would face on a planetary entry or during sustained hypersonic cruise, giving designers a way to validate heat shields and control surfaces before they ever leave the ground at the Plasmatron X facility.

NASA is also investing in new infrastructure, planning a next-generation wind tunnel at Langley that will prepare vehicles for the brutal descent through the thin air of Mars. Before a spacecraft lands on Mars, or futuristic concepts like inflatable decelerators are deployed, they must be designed and rigorously tested in wind tunnels that can simulate the right mix of speed, pressure, and atmospheric composition. The upcoming facility is part of a broader push to ensure that every new entry system, from robotic probes to human landers, survives the journey, a need highlighted in reporting that notes how such tunnels are essential before Mars missions ever fly.

Cracking the hypersonic “blackout” problem

As vehicles push deeper into hypersonic territory, one of the most stubborn challenges is the communications blackout that occurs when a sheath of ionized gas wraps around the craft. Once a vehicle hits those speeds, the plasma layer can block radio waves, cutting off telemetry and control at the very moment engineers most want data. At Colorado, Ali’s team is using their compact plasma tunnel to explore ways to manipulate that sheath, experimenting with shapes, materials, and possibly electromagnetic tricks to carve out windows in the plasma so signals can slip through, work that is explicitly framed as tackling what might be the most persistent challenge of hypersonic flight in Room to maneuver.

Solving that problem is not just about keeping astronauts on the line during reentry. It is also about enabling autonomous hypersonic vehicles, from future point-to-point passenger craft to high-speed cargo systems, to maintain guidance and navigation in the most hostile parts of their flight. By recreating blackout conditions in the lab, researchers can test antennas, coatings, and control algorithms under repeatable conditions, rather than waiting for a handful of risky flight tests. The same plasma tunnels that once focused on material survival are now becoming tools to probe the invisible electromagnetic environment around a vehicle, turning a long-standing vulnerability into a design variable that can be engineered and optimized.

Plasma engines: from lab pulses to Mars-class missions

While some teams use plasma to punish hardware, others are using it as a propellant that could make deep space travel dramatically more efficient. Pulsed plasma rocket concepts fire rapid bursts of ionized gas, accelerated by electric and magnetic fields, to achieve high exhaust velocities with far less propellant than chemical rockets. Analysts tracking the sector describe a growing ecosystem of companies and agencies working on such systems, with a recent market assessment projecting that plasma rocket propulsion could represent a $2.34 Bn opportunity by 2026 as operators chase better fuel efficiency.

Technical work is advancing in parallel. Detailed write-ups of pulsed plasma rocket propulsion describe how carefully timed electrical discharges can ionize a working fluid and then fling it out the back of a spacecraft at extreme speeds, trading raw thrust for sustained, efficient acceleration. One analysis notes that such systems could be especially attractive for deep space missions where every kilogram of propellant saved can be turned into more payload or faster transit, and it highlights how pulsed plasma designs are being refined to handle higher power levels and longer lifetimes.

NASA, Arizona innovators, and the race to Mars in weeks

NASA is not sitting on the sidelines. The agency is funding early-stage work on new plasma-based rockets that could slash travel times to Mars, backing concepts that combine nuclear power with advanced electric propulsion. Reporting on one such effort points to Arizona-based Howe Industries, which is developing a potentially groundbreaking system that uses a compact nuclear source to generate the electricity needed to accelerate plasma to very high exhaust velocities. The design aims to reach high velocities with remarkably high fuel efficiency, a combination that could make a Mars trip far less punishing for crews if the Arizona concept matures.

Separate coverage of plasma propulsion emphasizes that NASA is seeding a portfolio of such ideas, from pulsed systems to steady-state thrusters, in the belief that at least some will scale to operational missions. One analysis explicitly notes that NASA is funding the early stages of a new rocket propulsion system that could be the future of deep space travel, underscoring how seriously the agency takes the prospect of plasma-driven exploration. If these engines deliver, they would pair naturally with the new generation of plasma tunnels, since any craft capable of sustained high-speed transits will demand equally advanced testing of its thermal protection and control systems.

More from Morning Overview