Newly reprocessed radio observations are transforming the quiet reputations of nearby dwarf stars. What once looked like background hiss now resolves into violent, short‑lived outbursts that can dwarf the power of familiar solar flares and reshape how I think about habitable worlds around these small suns.

By combining sharper algorithms, more sensitive detectors, and lessons from other extreme radio sources, astronomers are uncovering a hidden population of stellar eruptions that had been buried in old data. The emerging picture is of a galaxy where even the smallest stars can unleash colossal storms, with consequences that reach from basic plasma physics to the prospects for life on planets in their orbit.

From dusty archives to explosive signals

The most striking change is not in the stars themselves but in how their signals are processed. I see teams going back to raw recordings from large radio arrays and running them through new pipelines that can pick out millisecond‑scale bursts and subtle polarization patterns that older software simply averaged away. Building on the expertise of researchers at Paris Observatory, PSL, and ASTRON, one international collaboration has focused specifically on stellar and exoplanetary systems, showing that careful reanalysis can reveal radio flashes that were effectively invisible in first‑pass surveys.

Those efforts are not happening in isolation. The same signal‑processing tricks that help isolate bursts from compact objects in the wider galaxy are now being applied to nearby dwarfs. Techniques honed on an unexplained space object that Astronomers at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, or ICRAR, flagged for its powerful, repeating signals are being repurposed to sift through the crowded region around sources like ASKAP J1832‑0911. By adapting methods originally designed to characterize that unexplained object, researchers can now distinguish dwarf‑star outbursts from background noise with far greater confidence.

Why cool red dwarfs are suddenly the loudest neighbors

Once the data are cleaned up, a clear pattern emerges: small, cool stars are unexpectedly boisterous at radio wavelengths. Cool red dwarfs are the most common sort of star in our Milky Way galaxy, and that sheer abundance means even rare events become frequent when scaled across hundreds of billions of systems. Earlier work on ultracool dwarf binaries showed that in at least one tight system both components are extremely low in mass yet still capable of dramatic activity, a point underscored when astronomers highlighted how these Cool red dwarfs broke records for their orbital and physical properties.

For me, the surprise is not just that these diminutive stars flare, but that their radio outbursts can rival or exceed those of much larger suns when measured relative to their size. Magnetic fields in such compact objects can be intensely tangled, and when they reconnect, they accelerate electrons to relativistic speeds that radiate strongly at radio frequencies. The reprocessed datasets show that what once looked like a handful of exotic cases is likely the tip of a much larger iceberg of ultracool dwarfs emitting coherent radio bursts, especially in close binary systems where tidal forces keep their interiors stirred and their dynamos active.

Lessons from extreme binaries and dead stars

To understand just how violent these outbursts can become, I find it useful to look at the most extreme compact systems astronomers have already cataloged. In one striking example, high‑speed optical detectors known as Andor iXon EMCCDs helped Support Discovery of Eclipsing White Dwarf Binary System In which the object ZTF J1539+5027, also labeled ZTF J153932.16+502738.8, revealed itself as an extraordinarily tight pair of stellar remnants. The white dwarfs in that system orbit so closely that their eclipses repeat in minutes, and the same sensitivity that captured those rapid dips in light can, in principle, be paired with radio arrays to catch equally fast electromagnetic bursts from similar binaries, as demonstrated in the Andor iXon observations.

Although white dwarf pairs are very different from low‑mass red dwarfs, they share a key trait: intense magnetic and gravitational environments that can drive coherent radio emission. When I compare the newly uncovered dwarf‑star bursts to the behavior of compact remnants, I see a continuum of phenomena rather than isolated curiosities. The same physical processes that power radio waves when a massive star dies in a dramatic explosion, leaving behind a dense core, also operate at lower energies in living stars that are still fusing hydrogen. That connection becomes clearer when I look at how researchers have linked certain strange repeating radio bursts to the aftermath of a star that dies in a, then compare those signatures to the scaled‑down storms now seen on nearby dwarfs.

Rewriting the risk map for exoplanets

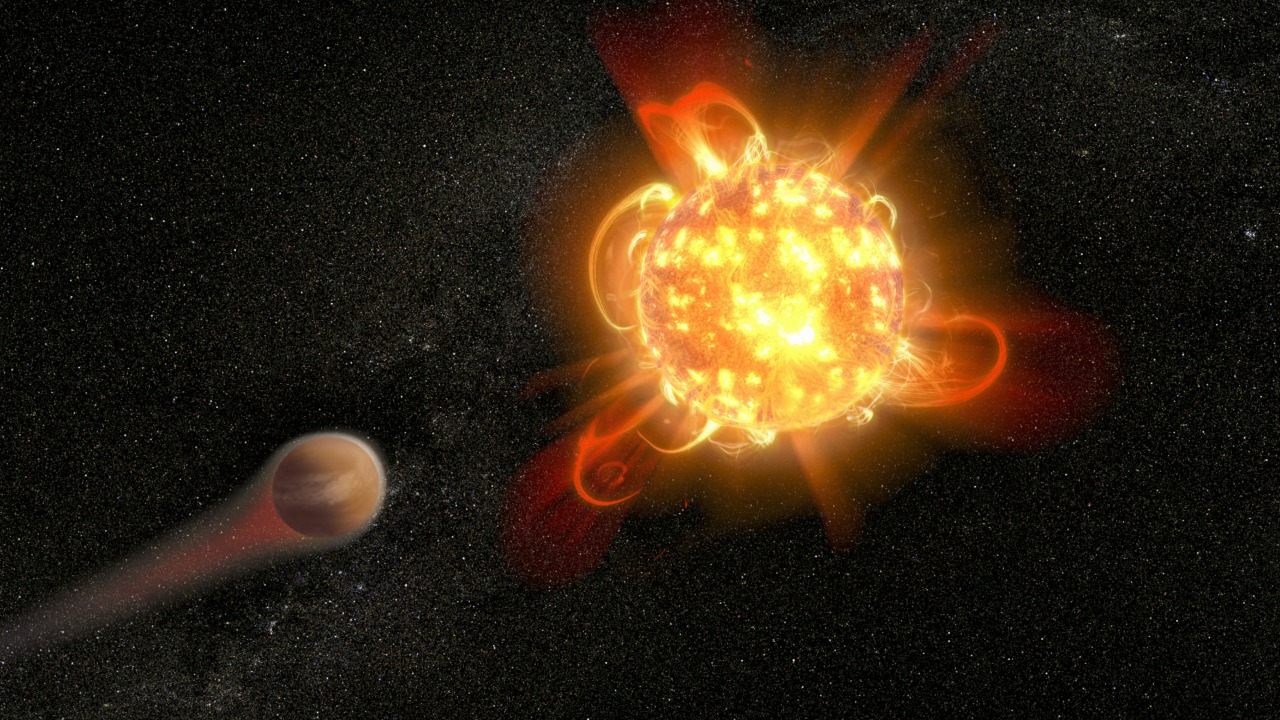

Once dwarf stars are recast as prolific radio bursters, the implications for planets in their orbit become hard to ignore. Many of the most publicized potentially habitable exoplanets, from Proxima Centauri b to the TRAPPIST‑1 family, circle cool stars at close range, where a single large flare can bathe them in high‑energy particles. The reprocessed radio data provide a new way to quantify that threat, since coherent bursts trace the most extreme magnetic reconnection events that are likely to drive coronal mass ejections and intense auroral currents. When I see repeated bursts from the same dwarf, I infer a chronically active magnetosphere that could strip atmospheres or at least subject them to relentless chemical erosion.

At the same time, radio outbursts offer a rare opportunity to probe exoplanetary environments directly. The same international team that focused on stellar and exoplanetary systems has shown that carefully tuned searches can pick up not only stellar flares but also potential signatures of star‑planet interactions, where a close‑in world modulates its host’s magnetic field and sparks periodic emission. By tying those patterns back to the expertise at Paris Observatory, PSL, and ASTRON, and by cross‑checking them against lessons from objects like ASKAP J1832‑0911, I see a path toward using radio storms as a diagnostic tool, not just a hazard warning, for the atmospheres and magnetospheres of planets around active dwarfs.

What the next wave of reprocessing could reveal

The current burst of discoveries is, in many ways, a proof of concept. If a handful of teams can pull shocking outbursts out of existing archives with improved algorithms, I expect a systematic reprocessing of major surveys to multiply the known sample of radio‑loud dwarf stars. Facilities that once focused on exotic transients in distant galaxies are already adapting their pipelines to flag nearby, low‑luminosity events, and the cross‑pollination between groups studying unexplained objects and those targeting cool stars is accelerating. Each new detection helps refine models of how magnetic fields are generated and dissipated in the smallest stellar bodies.

For me, the most intriguing prospect is that these efforts will blur the boundaries between categories that once felt distinct: ultracool dwarfs, white dwarf binaries, magnetars, and the mysterious repeaters that first drew attention to the radio sky’s volatility. As more archives are revisited and more sophisticated tools are deployed, I expect the quiet‑star stereotype to fade, replaced by a view of the local cosmos as a dynamic, crackling environment where even the faintest suns can erupt without warning. The reprocessed data are not just filling in gaps, they are forcing a rethink of how common extreme space weather really is in the neighborhoods where future telescopes will search for life.

More from Morning Overview