Quantum technology has moved from speculative physics to a strategic industry, and the stakes of what happens next are enormous. Hardware breakthroughs, surging investment and new national initiatives are converging to create a narrow window in which quantum could either become the next foundational computing platform or stall as a niche tool. I see the sector standing at a make-or-break moment, where technical progress, manufacturing capacity and policy choices will determine whether this becomes quantum’s transistor era or its forgotten prototype phase.

The new “transistor moment” for quantum

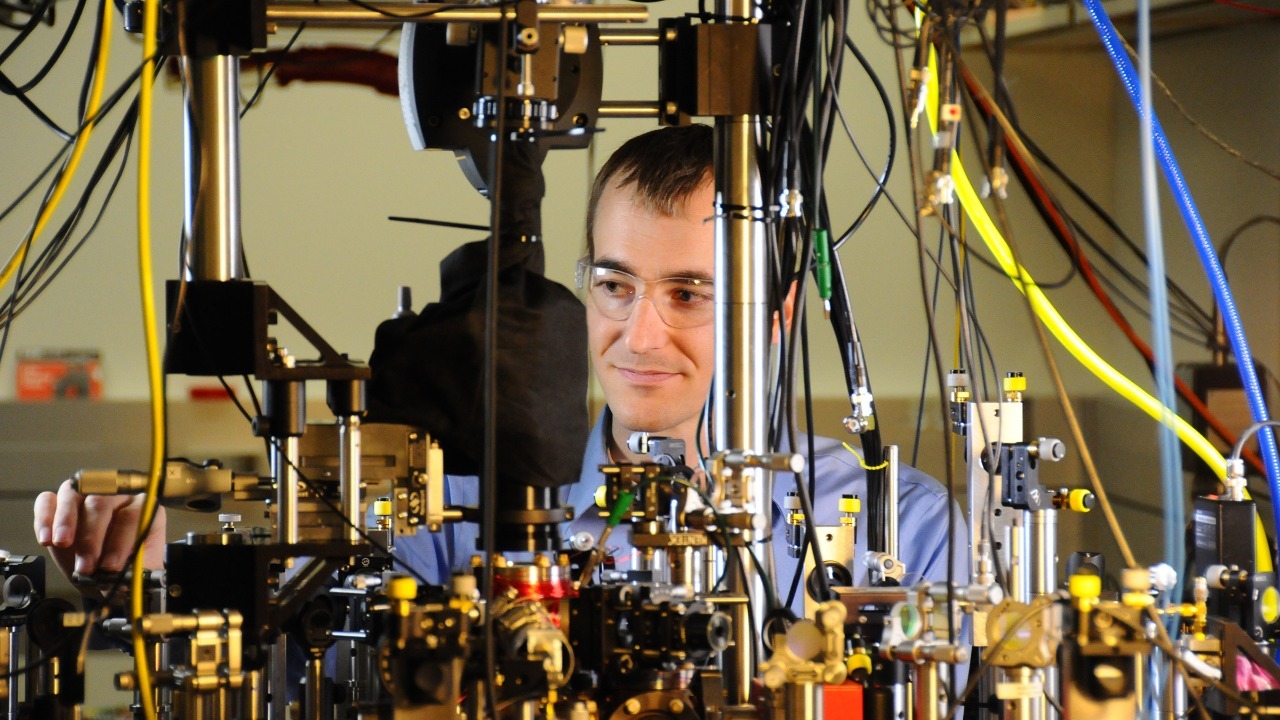

Researchers increasingly argue that quantum devices are reaching the same kind of inflection point that classical electronics hit when the transistor escaped the lab and began to reshape industry. Scientists have described current advances as a “Transistor Moment,” a phase in which quantum components are starting to look like reliable building blocks rather than fragile experiments, echoing how the transistor reshaped modern electronics in the mid twentieth century, a history that runs from Although the first tube to the work of Walter Houser Brattain and John Bardeen. That analogy is not marketing hype so much as a recognition that quantum hardware is finally being engineered with repeatability and scale in mind, as highlighted by scientists who frame today’s progress as Home Technology Quantum Tech Hits Its Transistor Moment Scientists Say.

The comparison to early microelectronics also captures the uncertainty of this stage, when it was not obvious which architectures would dominate or how quickly commercial demand would materialize. Analysts describe quantum information science as moving from theory into tools that can be deployed in communications, sensing and computing, a shift that mirrors the early decades of classical computing when microelectronics began to leave the lab and enter factories and offices, a transition traced in detail in assessments of how quantum technologies have reached a critical stage. I see this as the moment when quantum either consolidates into a real industry with standards, supply chains and customers, or remains a patchwork of impressive but isolated demonstrations.

2025: The International Year of Quantum raises the stakes

The timing of this inflection is not accidental, because 2025 has been designated the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, turning what might have been a quiet technical milestone into a global policy and public awareness event. The United Nations has proclaimed a year-long International Year of Quantum, known as IYQ, to highlight how quantum mechanics has moved from the initial development of quantum mechanics into technologies that could underpin secure communications, advanced sensors and new forms of computing. That kind of framing matters, because it signals to governments and investors that quantum is no longer a niche research topic but a strategic capability.

National labs and research consortia have seized on this designation to argue that the world is entering a new era of quantum deployment rather than just experimentation. At Oak Ridge National Laboratory, for example, researchers describe how Quantum computers have been available to researchers for years but are only now starting to look like tools that can be integrated into broader workflows, a shift they characterize as the dawn of a new era. In a more detailed review, Oak Ridge scientists note that Quantum takes off in the same year that the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology focuses global attention on these systems, reinforcing the sense that 2025 is a hinge point rather than just another incremental step.

Investment hits a “magic moment”

Capital is following that narrative, and the flow of money is one of the clearest signs that quantum is entering a make-or-break phase. Analysts describe quantum technology investment as hitting a “magic moment,” with the quantum computing industry making the leap from research and development to deployment and wider adoption, and with a smart mix of private and public funding creating an array of opportunity that still depends on careful execution, a dynamic captured in detail in assessments of how quantum technology investment hits a magic moment. Market projections are equally aggressive, with market analysts expecting the global quantum computing industry to grow from $1.3 billion in 2024 to tens of billions of dollars over the next decade, a trajectory that would put quantum among the fastest growing technology sectors of the decade.

Broader estimates for the entire quantum sector, which include sensing and communications as well as computing, point to even larger stakes. One widely cited forecast suggests the quantum sector could be worth up to $97 billion, or £74 billion, by 2035, even as AI is forecast in the trillions, a comparison that underscores both the promise and the relative scale of quantum. I read those numbers as a double-edged sword: they are large enough to attract serious investors and national strategies, but still small enough that a few high-profile failures or delays could cool enthusiasm quickly if the technology does not deliver practical value.

Hardware milestones: from Helios to IonQ’s record

Behind the investment headlines, concrete hardware milestones are giving the field its current momentum. Scientists have unveiled Helios, a record-breaking superconducting system that researchers describe as “easily the most powerful quantum computer on Earth,” built with 98 qubits and designed to deliver new insights into superconducting physics. That kind of system does not yet solve commercial optimization problems on its own, but it demonstrates that engineering teams can assemble and control increasingly complex quantum processors, a prerequisite for any future fault-tolerant machine.

Trapped-ion platforms are also crossing thresholds that insiders have treated as long-term targets. IonQ has announced a landmark result that sets a new world record in quantum computing performance, describing how This level of quantum performance has been the industry’s north star for decades and arguing that crossing it brings fault-tolerant quantum computing into view for applications such as autonomous vehicles and artificial intelligence. In a parallel statement, the company emphasizes that This new world record represents a critical technical milestone on its roadmap, translating directly into fewer errors per operation. I see these achievements as proof that multiple hardware approaches are maturing at once, which is healthy for the ecosystem but also raises the pressure to show that such performance gains translate into real-world advantage.

From lab curiosity to deployed systems

One of the clearest signs that quantum is leaving the lab is the way national labs and defense-focused organizations now talk about deployment rather than demonstration. At Oak Ridge, researchers note that quantum computers have been available to scientists for roughly eight years, but until recently they were treated as exotic tools for a narrow set of experiments; now they argue that Quantum hits the big time as these machines start to integrate with high performance computing workflows and industrial use cases. In a more expansive review, Oak Ridge researchers describe how Quantum takes off in 2025, aligning with the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology and signaling that the focus is shifting from proof-of-concept experiments to production-grade services.

Defense and manufacturing analysts are even more blunt about the shift from prototypes to products. Commentators describe how quantum systems for sensing, navigation and secure communication are no longer just fascinating demonstrations, but working systems with paying customers, deployed on timelines measured in months rather than decades, and they warn that whoever controls the manufacturing base effectively controls the pathway to production, a point made starkly in discussions of America’s quantum manufacturing moment. I read that as a reminder that this make-or-break phase is not just about physics, but also about supply chains, fabrication plants and the ability to scale devices from dozens of units to thousands.

Noise, memory and the hard physics still in the way

For all the progress, the physics of quantum systems still imposes brutal constraints that could slow or even derail the current momentum if they are not addressed. Engineers working on superconducting platforms describe how the control electronics that drive qubits can themselves introduce noise, and how the biggest challenge is not upper management’s reaction to launch dates but the stubborn reality that every cable, amplifier and microwave pulse can degrade fragile quantum states, a problem explored in depth in analyses of how Not only the qubits but also the control electronics created noise. Even when companies announce breakthroughs, skeptics point out that some of these milestones still do not translate into solutions for real-world problems, as seen in debates over whether Has Google truly made a quantum breakthrough if its latest demonstration cannot yet tackle commercially relevant workloads.

New research on decoherence and memory effects underscores how far there is to go before large-scale, reliable quantum computers become routine. Experimental teams have shown that quantum computers can suffer memory problems over time, with qubit states drifting in ways that are hard to predict, and they have had to use software to work backwards from measurement data to infer what state the system was in, a painstaking process described in studies of why Then the researchers used software to reconstruct the system’s history. At the same time, device physicists point out that classical electronics continues to push its own limits, with experiments showing that Nevertheless Ohm’s law can hold down to the atomic scale, and that Simmons and colleagues, who note that Five years ago there were many more barriers, still see the core challenge for quantum computing as making a scalable system. I see this as the crux of the make-or-break moment: quantum must improve faster than classical alternatives while overcoming its own fundamental fragility.

Quantum and classical: rivals or power couple?

Rather than replacing classical computing outright, quantum is increasingly framed as a specialist partner that will slot into existing high performance computing stacks. Analysts argue that quantum computing and HPC are likely to form a “future power couple,” with quantum accelerators handling specific optimization or simulation tasks while classical supercomputers manage data movement, error mitigation and large-scale orchestration, a relationship explored in detail in discussions of how Quantum computing will pair with HPC. That framing lowers the bar for what counts as success in the near term, since quantum systems do not need to be general-purpose machines to be valuable; they just need to outperform classical methods on a handful of high-value problems.

At the same time, classical computing is not standing still, which raises the performance bar quantum must clear to justify its cost and complexity. Analysts note that Meanwhile classical computing continues to raise the bar through advances in hardware such as GPUs and specialized accelerators, as well as through algorithmic improvements that squeeze more performance out of existing architectures. I see the emerging consensus as a pragmatic one: quantum will likely succeed not by displacing classical systems, but by integrating with them in hybrid architectures that can be upgraded over time as quantum hardware and error correction improve.

Geopolitics and the race to manufacture at scale

Quantum’s make-or-break moment is also geopolitical, because governments increasingly treat control of quantum technologies as a strategic asset. Commentators warn that “whoever controls quantum computing will control the world,” arguing that we are just beginning to understand how strong and destructive AI can be and that there have been too few guardrails around emerging technologies, a concern laid out starkly in interviews that stress how Aug and There is a belief that the balance of power is going to change completely. That rhetoric may sound dramatic, but it reflects real concerns about quantum’s potential to break current cryptographic systems and to give early adopters an edge in fields like materials discovery and logistics.

Funding patterns show how seriously states are taking that race. Analysts report that China leads in government quantum funding with over $15 billion allocated across communications, computing and cryptography, a figure that dwarfs many Western national programs and has spurred calls for more coordinated responses. In the United States, experts argue that the country is entering America’s quantum manufacturing moment, where the key question is not whether prototypes can be built, but who will own the fabs, supply chains and standards that turn those prototypes into mass-produced systems. I see this as another dimension of the make-or-break phase: if democratic states fail to build robust quantum manufacturing ecosystems now, they may find themselves dependent on rivals for critical infrastructure later.

Beyond computing: sensing, communications and the broader stack

While quantum computing grabs most of the headlines, other branches of quantum technology may reach commercial maturity sooner and help sustain the broader ecosystem. Analysts argue that the three core pillars of quantum technology, quantum computing, quantum communication and quantum sensing, are all advancing, and that some of the fastest growth may come from applications like secure links and ultra-precise measurement, a trend highlighted in research that notes how Our new research shows these pillars moving from concept to reality. In particular, quantum sensing has entered a pivotal phase, with real-world application development now central to unlocking its full potential, a point reinforced in assessments that describe how Quantum sensing is shifting from lab prototypes to production and deployment.

These adjacent domains matter because they can generate revenue and industrial know-how even before large-scale quantum computers are available. Secure quantum communication links, for example, can be deployed along critical infrastructure routes, while quantum sensors can improve navigation in GPS-denied environments or enhance medical imaging. Analysts who ask whether quantum will be bigger than AI point out that Meanwhile AI is forecast in the trillions, which suggests that quantum’s best path to impact may be as an enabling layer that quietly improves existing systems rather than as a standalone consumer technology. I see the success of sensing and communications as a hedge for the industry: if full-scale quantum computing takes longer than expected, these other pillars can still justify continued investment and talent development.

The human bottleneck: talent, software and ecosystems

Even if the physics and hardware cooperate, the quantum sector faces a human and organizational bottleneck that could limit its growth. Industry surveys warn that Challenges Ahead include Talentshortages in quantum and growth-stage funding outside the US, identified as two of the biggest systemic risks to the industry’s continued growth. That diagnosis shifts the conversation from qubit counts to questions about who will write the software, design the algorithms and build the middleware that makes quantum hardware usable by non-specialists.

Education initiatives are trying to close that gap, but they are racing against time. Organizations such as the Chicago Quantum Exchange emphasize that 2025 is the year of quantum not just in terms of hardware, but also in terms of training the next generation of engineers, computer scientists and policy experts who can navigate this new landscape. I see software platforms as the quiet hinge of this make-or-break moment: without robust development environments, cloud access models and domain-specific libraries, even the most powerful quantum processors will remain underused curiosities.

Why this moment will not last

All of these threads, from hardware milestones and investment surges to geopolitical jockeying and talent shortages, point to a narrow window in which decisions made now will shape quantum’s trajectory for decades. Analysts who look at the long-term forecast argue that quantum computing’s prospects still look bright, but they also stress that realizing that potential will require sustained effort to integrate quantum with classical systems, improve error correction and build viable business models, a balance captured in assessments that note how Meanwhile classical computing continues to advance. The risk is not that quantum will disappear, but that it could plateau as a specialized tool used by a handful of labs and defense contractors rather than becoming a broadly transformative technology.

History suggests that such windows close quickly. The path from the first vacuum tubes to modern microprocessors, traced from Although the earliest devices to the present day, was shaped as much by manufacturing, standards and software ecosystems as by physics breakthroughs. Quantum now faces a similar test, with Helios-scale machines, IonQ’s record-setting performance and national manufacturing pushes all signaling that the technology is ready to leave the lab. Whether it does so at scale will depend on how quickly industry, governments and researchers can turn this fleeting “Transistor Moment” into durable infrastructure before the opportunity, and the patience of investors and policymakers, runs out.

More from MorningOverview