Programmable CRISPR tools are turning stem cell biology into something closer to software engineering, shrinking reprogramming timelines from months of trial and error to carefully scripted interventions that can play out in weeks. By shifting from blunt genetic edits to precise control of when and how genes switch on, researchers are starting to treat cell fate as a tunable parameter rather than a fixed outcome. If this approach holds up, it could reset expectations for drug discovery, disease modeling, and eventually regenerative therapies.

From slow alchemy to programmable timelines

For most of the past decade, turning adult cells into induced pluripotent stem cells has felt like biological alchemy, with scientists nudging cultures along for months and hoping they land in the right state. Conventional protocols rely on viral delivery of reprogramming factors that integrate into the genome, which can be effective but often produce mixed cell populations and unpredictable timing. The promise of programmable CRISPR systems is that I can now think about reprogramming as a controlled sequence of gene activations, designed in advance and executed on a schedule.

Instead of permanently rewriting DNA, CRISPR-based activators attach to specific promoters and dial up endogenous genes that drive pluripotency, which lets researchers choreograph the transition from one identity to another. Work using CRISPR activation, often abbreviated CRISPRa, has shown that these CRISPRa cells are reprogrammed with higher fidelity than cells pushed by transgenic overexpression, directly challenging the idea that slow, conventional methods are the gold standard. That shift in mindset, from waiting for cells to cooperate to programming them to comply, is what makes compressed timelines plausible.

Why pluripotent stem cells are worth the race

The urgency around faster reprogramming is not just about lab convenience, it is about unlocking what pluripotent stem cells can actually do. Human pluripotent stem cells, often abbreviated PSCs, can give rise to all somatic lineages, meaning they can generate cells that would have arisen from all three embryonic layers, including ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. When I look at that capacity, I see a single starting material that could, in principle, be steered into neurons for Parkinson’s models, cardiomyocytes for heart failure screens, or hepatocytes for toxicology testing.

That breadth is why PSCs sit at the center of plans for disease modeling, cell replacement therapies, and high throughput screening. As one overview of PSCs can give rise to all somatic lineages makes clear, realizing this potential requires reliable genome engineering and differentiation protocols that do not introduce unwanted mutations or epigenetic scars. Programmable CRISPR tools that shorten and standardize the journey into pluripotency are therefore not a side story, they are a prerequisite for turning PSCs into a routine platform for regenerative medicine.

CRISPR activation as a cleaner on‑ramp to pluripotency

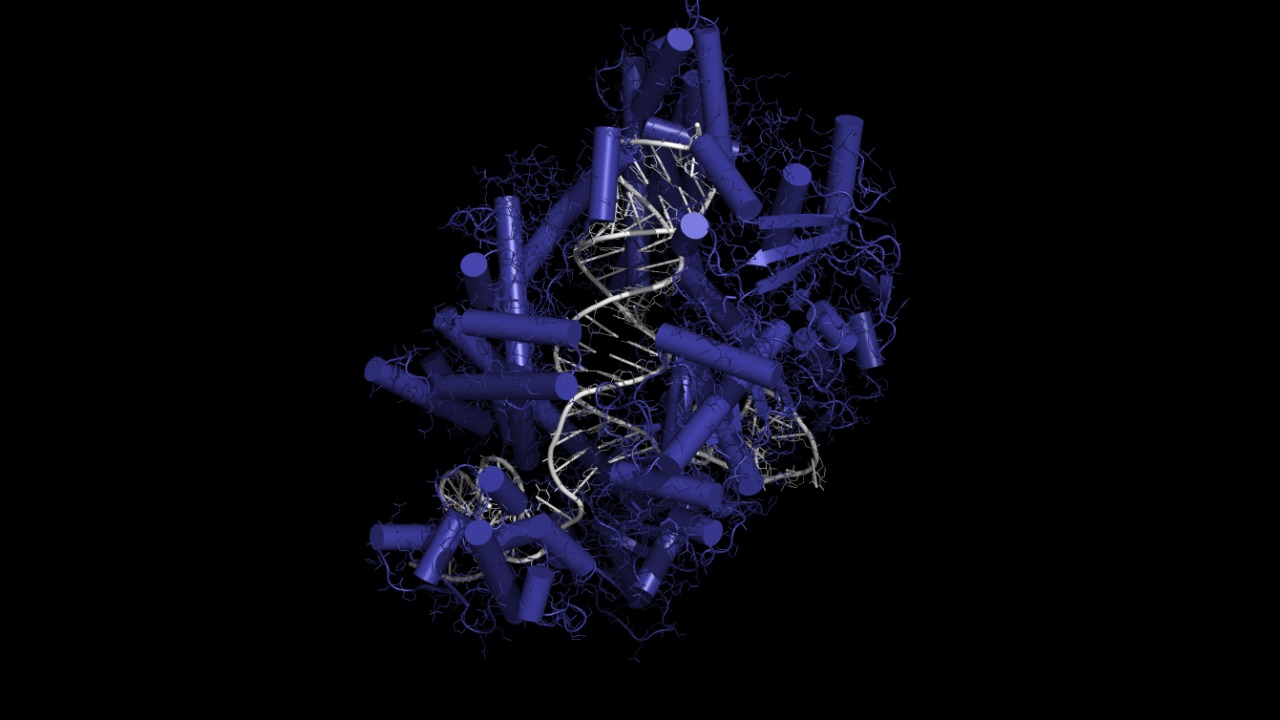

What makes CRISPR activation so compelling in this context is its ability to flip on native genes without cutting DNA, which sidesteps many of the risks that come with integrating transgenes. In CRISPRa systems, a catalytically dead Cas9 is fused to transcriptional activators and guided to promoters that control pluripotency factors, effectively turning the cell’s own circuitry into the driver of reprogramming. When I compare that to viral overexpression, which can land randomly in the genome and stay active indefinitely, the appeal of a programmable, nonintegrating switch is obvious.

Evidence that this is more than a conceptual upgrade comes from experiments showing that CRISPRa cells are reprogrammed with higher fidelity than cells generated by conventional transgenic methods, with fewer aberrant gene expression patterns and more consistent pluripotent signatures. Because the activator complexes can be turned off once reprogramming is complete, they also reduce the risk that pluripotency factors linger and destabilize downstream differentiation. In practical terms, that means I can imagine a workflow where fibroblasts are converted into high quality pluripotent lines on a predictable schedule, ready for differentiation in weeks rather than languishing in culture for months.

Programmable epigenome editing tightens control of timing

CRISPR activation is only one piece of the timing puzzle, because cell fate is governed not just by which genes are present but by how chromatin is packaged and which regulatory marks sit on top of DNA. Programmable epigenome editors extend the CRISPR toolkit by fusing dead Cas9 to enzymes that add or remove epigenetic marks, letting researchers open or close chromatin at specific loci without touching the underlying sequence. When I think about compressing reprogramming timelines, the ability to rapidly erase a somatic epigenetic identity and install a pluripotent one is at least as important as turning on a handful of transcription factors.

Delivering these editors efficiently and transiently has been a major bottleneck, which is why newer strategies that use engineered virus like particles to carry CRISPR ribonucleoprotein complexes are so significant. In one such approach, researchers describe how Here, we leverage engineered particles to transiently deliver various CRISPR epigenome editor RNPs for programmable editing, creating a pulse of activity that can reset chromatin without permanent cargo. That kind of transient, programmable intervention is exactly what a compressed, weeks long reprogramming protocol needs, because it lets scientists schedule epigenetic changes alongside gene activation in a coordinated script.

From genetic editing to functional stem cell products

Speed only matters if the resulting stem cells are useful, and here CRISPR’s track record in functional differentiation is starting to pay dividends. The CRISPR Cas9 system has already been used for genetic modification of stem cells that are then pushed to differentiate into specific cell types for functional studies, including disease relevant tissues. When I look at those experiments, I see proof that precise editing can be layered on top of reprogramming to create bespoke cell lines that carry defined mutations or reporters, ready for downstream assays.

In the context of oral cancer, for example, researchers have shown that The system has been used for genetic modification of stem cells, leading to the differentiation of specific cell types for functional cancer research and potential therapeutic applications. That same logic applies to cardiology, neurology, and immunology, where disease modeling depends on having the right mutations in the right cell types. If programmable CRISPR reprogramming can deliver those starting stem cell lines in weeks, the entire pipeline from patient sample to functional assay compresses, which is where the real impact on research timelines will be felt.

The Jekyll and Hyde problem of stemness

Any attempt to accelerate stem cell workflows has to grapple with the uncomfortable fact that the same traits that make stem cells powerful can also make them dangerous. One of the profound abilities of stem cells that makes them an ideal tool for cell based therapy is the ability to differentiate into multiple lineages depending on intrinsic or extrinsic stimulations. That plasticity is the engine behind regenerative medicine, but it is also what gives rise to cancer stem cells that can seed tumors and resist treatment.

When I think about programmable CRISPR systems in this light, I see both a risk and an opportunity. On the one hand, more efficient reprogramming could, if poorly controlled, increase the chance of generating cells with unintended self renewal properties. On the other, precise control over gene expression and epigenetic state offers a way to steer cells away from malignant trajectories. Analyses of One of the profound abilities of stem cells to switch lineages underscore why safety checks must be built into any accelerated protocol, from rigorous genomic screening to functional assays that confirm cells exit the pluripotent state cleanly.

Industry moves toward high‑quality, high‑throughput lines

While academic labs refine the underlying biology, specialized companies are already reorganizing their business models around faster, more programmable reprogramming. Contract providers that once focused on bespoke, months long projects are now marketing platforms that can generate standardized induced pluripotent stem cell lines at scale. In that landscape, the competitive edge is not just speed but the ability to deliver lines that are genetically stable, well characterized, and ready for industrial workflows like automated screening.

One example is a service that emphasizes how, Importantly our method produces the highest quality stem cell lines for research, which in turn allows the company to undertake big reprogramming projects and support clients using stem cells in drug discovery. When I connect that claim to the emerging CRISPR toolkit, it is clear that commercial players are betting on programmable reprogramming as a way to turn what used to be artisanal cell line generation into a repeatable, semi automated service. If they can reliably compress timelines from months to weeks without sacrificing quality, pharmaceutical partners will quickly recalibrate their expectations for how fast new disease models should appear.

What compressed timelines mean for drug discovery

For drug developers, the most immediate impact of programmable CRISPR reprogramming is on how quickly they can move from a genetic insight to a testable model. Today, identifying a pathogenic variant in a patient cohort is only the beginning, because building a relevant cell system to study that variant can take months of reprogramming, editing, and differentiation. If I can instead script a CRISPRa and epigenome editing protocol that converts patient fibroblasts into pluripotent cells and then into the affected lineage on a fixed, weeks long schedule, the feedback loop between genomics and functional validation tightens dramatically.

That acceleration matters for phenotypic screening, where large panels of compounds are tested on disease relevant cells to see which ones rescue a phenotype. With programmable CRISPR tools, it becomes feasible to generate multiple isogenic lines that differ at only one or two loci, then differentiate them in parallel and run side by side assays. The foundational work showing that PSCs can give rise to all somatic lineages means those assays can, in principle, be built for almost any tissue. The bottleneck shifts from biology to logistics, which is exactly the kind of problem pharmaceutical companies know how to solve.

Ethical and regulatory pacing in a faster era

As reprogramming speeds up, ethical and regulatory frameworks that were built around slower, more manual processes will come under pressure. Institutional review boards and regulators have grown accustomed to stem cell projects that unfold over long timelines, with multiple checkpoints where safety and consent can be revisited. If programmable CRISPR protocols allow a lab to go from patient biopsy to edited pluripotent line and differentiated cells in a matter of weeks, those oversight mechanisms will need to adapt so they do not become either a rubber stamp or a bottleneck.

I see a particular challenge in the blurred line between research and preclinical development. When CRISPR Cas9 is used so that The system has been used for genetic modification of stem cells that feed directly into therapeutic applications, regulators will want assurance that compressed timelines do not hide off target effects or unstable epigenetic states. That likely means building standardized characterization panels into every accelerated workflow, from whole genome sequencing to long term differentiation assays, so that speed does not come at the expense of safety or public trust.

More from MorningOverview