A tiny prehistoric bird from the early Cretaceous has turned into one of the strangest death scenes in the fossil record, its last moments frozen with a throat packed full of stones. The animal, roughly sparrow sized and about 120 million years old, appears to have swallowed more than 800 pebbles in a fatal cascade that scientists are still struggling to explain. Instead of solving a puzzle about ancient bird digestion, the fossil has opened a deeper mystery about behavior, evolution, and the thin line between adaptation and catastrophe.

As I trace what researchers have uncovered so far, the picture that emerges is not just a grisly curiosity but a rare snapshot of how early birds lived and died. The stone filled throat hints at complex feeding habits, possible illness, and even psychological stress, yet none of the usual explanations quite fit the evidence. That tension between a vividly preserved death and an elusive motive is what makes this fossil so compelling.

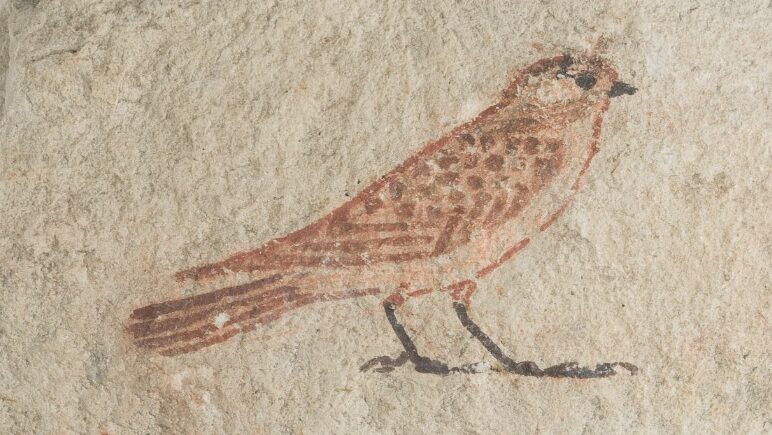

The fossil that should not exist

The starting point is the fossil itself, a delicately preserved skeleton from the early Cretaceous that looks, at first glance, like many other small birdlike specimens from that era. What sets it apart is the dense cluster of tiny rocks jammed into the neck and upper chest, more than 800 individual stones packed so tightly that they form a solid mass where soft tissue once sat. In typical bird fossils, a few rounded pebbles in the gut can signal normal digestion, but this concentration in the throat region is so extreme that it immediately flagged something unusual in the animal’s final moments, as described in detail in one analysis of the 800 stones.

In life, this bird would have been light and agile, with hollow bones and a body plan tuned for flight, yet its death scene is dominated by weight, density, and blockage. The stones are not scattered through the abdomen the way normal digestive pebbles are, but instead appear to have clogged the esophagus and upper digestive tract, forming a plug that likely cut off airflow. That anatomical pattern is what led researchers to conclude that the animal did not simply die and later become surrounded by debris, but instead choked to death as the stones piled up inside its own throat.

A 120-Million-Year snapshot of disaster

To understand the scale of this event, it helps to place the bird in time. The fossil comes from a period roughly described as 120-Million-Year, a slice of the early Cretaceous when feathered dinosaurs and the first true birds were diversifying across ancient landscapes. In that context, a small avian choking incident might sound trivial, yet the sheer number of pebbles involved, more than 800, makes this one of the most dramatic examples of fatal ingestion on record. Reports on this 120-Million-Year specimen emphasize that the animal was a genuinely Old Bird Choked To Death On Over Stones, Why it did so remaining unresolved.

What makes this moment in deep time so vivid is that the fossil captures not just bones but behavior in its final, catastrophic expression. Around the same 120-Million-Year interval, other fossils show birds experimenting with different diets, beak shapes, and flight styles, yet none display anything like this level of stone ingestion. The contrast suggests that whatever drove this individual to keep swallowing pebbles was not a routine feature of its species’ lifestyle, but a rare, perhaps pathological event that happened to be preserved with extraordinary clarity.

How birds normally use stones

Modern birds offer a crucial baseline for interpreting what went wrong. Many species, from chickens to pigeons to ostriches, deliberately swallow small stones that settle in a muscular organ called the gizzard, where they help grind up tough food like seeds and plant fibers. These gizzard stones, or gastroliths, are typically few in number and confined to the stomach region, not the throat. In healthy animals, the process is controlled and limited, which is why the fossil’s massive stone load stands out so sharply against normal avian biology, a point underscored in coverage that contrasts typical digestion with the bird that swallowed Around 120 m years ago and died from suffocation.

In living species, the stones are usually smooth, rounded, and selected from the environment with some care, then retained or expelled as needed. The pattern is so consistent that paleontologists often use clusters of stones in the gut to infer diet and behavior in extinct animals. That is why the Cretaceous bird’s stone filled throat is so disruptive: instead of a tidy packet of gastroliths in the gizzard, the rocks appear in the wrong place, in the wrong quantity, and in a configuration that points to a lethal blockage rather than efficient digestion. The fossil forces me to separate the idea of purposeful stone use from the possibility of a behavior that spiraled out of control.

Reconstructing a choking death

From the arrangement of the skeleton and the position of the stones, researchers have pieced together a likely cause of death that is as straightforward as it is unsettling. The bird seems to have swallowed pebble after pebble until its esophagus and upper digestive tract were crammed full, leaving no clear passage for air. The stones are stacked in a tight column that rises into the neck, a configuration that strongly suggests suffocation rather than a slow digestive failure. One detailed account describes how, around 120 million years ago, the animal swallowed over 800 tiny stones and ultimately died from suffocation linked directly to the rock filled throat.

To test whether the stones might have been reworked into the body after death, scientists examined their distribution and relationship to the bones. The pebbles are tightly associated with the soft tissue spaces where the esophagus and crop would have been, and they do not show the scattered, random pattern expected if water or sediment had simply washed them in. Instead, the fossil reads like a freeze frame of a living process that went fatally wrong, with each stone representing a deliberate swallow that brought the bird one step closer to asphyxiation.

Why gizzard stones do not fit the evidence

At first glance, it might be tempting to interpret the stones as an extreme case of gizzard loading, but the anatomy argues against that simple explanation. In typical birds that use gastroliths, the stones sit lower in the body, clustered in the muscular stomach rather than stacked in the neck. Here, the bulk of the pebbles appears to be lodged higher up, in the region corresponding to the esophagus and possibly a crop, which is not where grinding stones do their work. One analysis notes that when anatomists compared the fossil layout to modern birds, they concluded that the rocks were stuck in the bird’s esophagus rather than in a functional gizzard.

The sheer number of stones also strains the gizzard hypothesis. Even large, seed eating birds that rely heavily on gastroliths do not approach a count in the hundreds, let alone more than 800. The fossil’s tally suggests a behavior that overshot any plausible digestive need, turning a helpful adaptation into a lethal overload. That mismatch between expected function and observed pattern is what pushes scientists to look beyond routine feeding and consider more unusual drivers, from disease to neurological disturbance.

Illness, stress, or something stranger?

Once normal digestion is ruled out, the question shifts from how the bird died to why it kept swallowing stones long past the point of safety. One line of thinking focuses on illness, drawing parallels with modern birds that exhibit odd or repetitive behaviors when they are unwell. In some species, sickness can trigger pica like tendencies, where animals ingest non food items in a way that seems disconnected from immediate survival. A detailed discussion of the fossil suggests that One explanation is illness, noting that birds alive today can behave very strangely when they are unwell and that a distressed One might do something similar in a bad state.

Another possibility is that environmental stress or a sudden change in food availability pushed the bird toward desperate foraging, with stones accidentally mixed in or misidentified as edible items. Yet the consistency and size of the pebbles suggest some degree of selection rather than random gulping. That tension leaves room for more speculative ideas, such as neurological disorders or developmental abnormalities that could have disrupted the animal’s ability to regulate feeding. While none of these scenarios can be confirmed from bones and stones alone, they highlight how a single fossil can force scientists to confront the limits of what behavior can be inferred from anatomy.

What the stones themselves reveal

The pebbles are not just a body count; their size, shape, and distribution carry clues about how they were gathered and swallowed. Reports describe them as tiny, relatively uniform stones, suggesting that the bird repeatedly picked up similar sized grains rather than randomly scooping sediment. That pattern points to a deliberate, repeated action, whether driven by normal foraging instincts gone awry or by some internal compulsion. A social media summary of the find notes that a 120-million-year Fossil was found with over 800 stones lodged in its throat, framing the rock cluster as an Fossil level evolutionary mystery.

The location of the stones, concentrated in the throat rather than scattered through the body cavity, also argues against postmortem disturbance. If water currents or scavengers had moved the pebbles, they would likely appear in a more chaotic pattern, mixed with sediment and detached bones. Instead, the stones form a coherent mass that mirrors the shape of the soft tissues they once occupied, reinforcing the idea that they were in place at the moment of death. For me, that makes the stones less like passive geological debris and more like active participants in the bird’s final behavior.

A tiny bird with big evolutionary questions

Beyond the immediate drama of choking, the fossil raises broader questions about how early birds experimented with feeding strategies and how fragile those experiments could be. This sparrow sized animal lived at a time when avian lineages were still branching out from their dinosaur ancestors, testing different diets, habitats, and body plans. The fact that such a small creature could interact with its environment in a way that led to swallowing more than 800 stones hints at a complex behavioral repertoire, even if the outcome was disastrous. One overview of the discovery emphasizes that this prehistoric bird, preserved in a collection that includes material from the Field Museum in Chicago, choked to death on 800 rocks and that no one yet knows why it was swallowing them in the first place.

From an evolutionary perspective, the fossil underscores how adaptations that are generally beneficial can carry hidden risks. The use of stones to aid digestion is a clever solution that has evolved in multiple lineages, yet in this case, something about the bird’s physiology or behavior pushed that strategy beyond its safe limits. The result is a cautionary tale written in rock and bone, reminding me that natural selection works with trial and error, and that not every behavioral variant is a step toward long term success. Some, like this bird’s fatal stone binge, are evolutionary dead ends that survive only as haunting snapshots in the fossil record.

The enduring mystery and what comes next

For now, the prehistoric bird with a throat full of stones sits at the intersection of anatomy, behavior, and speculation, a case study in how much and how little a single fossil can tell us. The physical evidence is clear enough to reconstruct a choking death, but the motivations behind the behavior remain stubbornly opaque. As more early bird fossils are examined with modern imaging and analytical tools, researchers will be watching closely for any hint of similar stone loading, which could reveal whether this was a one off tragedy or part of a broader, poorly understood pattern in Cretaceous ecosystems. One detailed feature on the find captures this tension, noting that Dec reports about the bird’s final moments have only deepened the puzzle of why it swallowed so many stones in the first place, even as they clarify that it died with a throat full of Dec era pebbles.

In the meantime, the fossil has already reshaped how I think about the deep past. It is easy to imagine ancient life in broad strokes, as a parade of species evolving and going extinct over millions of years, but this bird’s final act is intimate and specific, a moment of panic and suffocation that could just as easily play out in a modern backyard if a pigeon or chicken made the same fatal mistake. That continuity across 120 million years, from a tiny Cretaceous bird to the flocks that live alongside us today, is what makes this stone choked skeleton more than a curiosity. It is a reminder that even in prehistory, lives were lived one decision at a time, and sometimes, as this fossil shows with brutal clarity, a single behavior could tip the balance between survival and death.

More from MorningOverview