Planet 9 sits at the edge of scientific imagination, promising either an epic expansion of the Solar System or a lesson in how easily patterns can mislead us. As new data arrive and old assumptions are challenged, the mystery keeps deepening, forcing astronomers to decide whether they are chasing a real world or a cosmic illusion.

1. Caltech Duo Proposes Planet Nine in 2016

Caltech astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown ignited the Planet 9 debate in 2016 when they proposed a massive, unseen planet lurking beyond Neptune. They argued that a distant world could naturally explain why several extreme trans-Neptunian objects, or eTNOs, follow clustered, elongated paths in the outer Solar System. In their view, only a substantial gravitational perturber could keep those orbits aligned over billions of years, turning a curious pattern into a testable prediction.

The pair described how mathematical modeling and computer simulations of these distant bodies pointed toward a new planet, which they named Planet Nine. By treating the eTNOs as tracers of an invisible mass, they reframed the outskirts of the Solar System as a dynamical puzzle. If their interpretation is right, the discovery would reshape planetary science, forcing textbooks to add a new member to the planetary family and revisiting how giant planets formed and migrated.

2. Mass Estimate of 5–10 Earth Masses

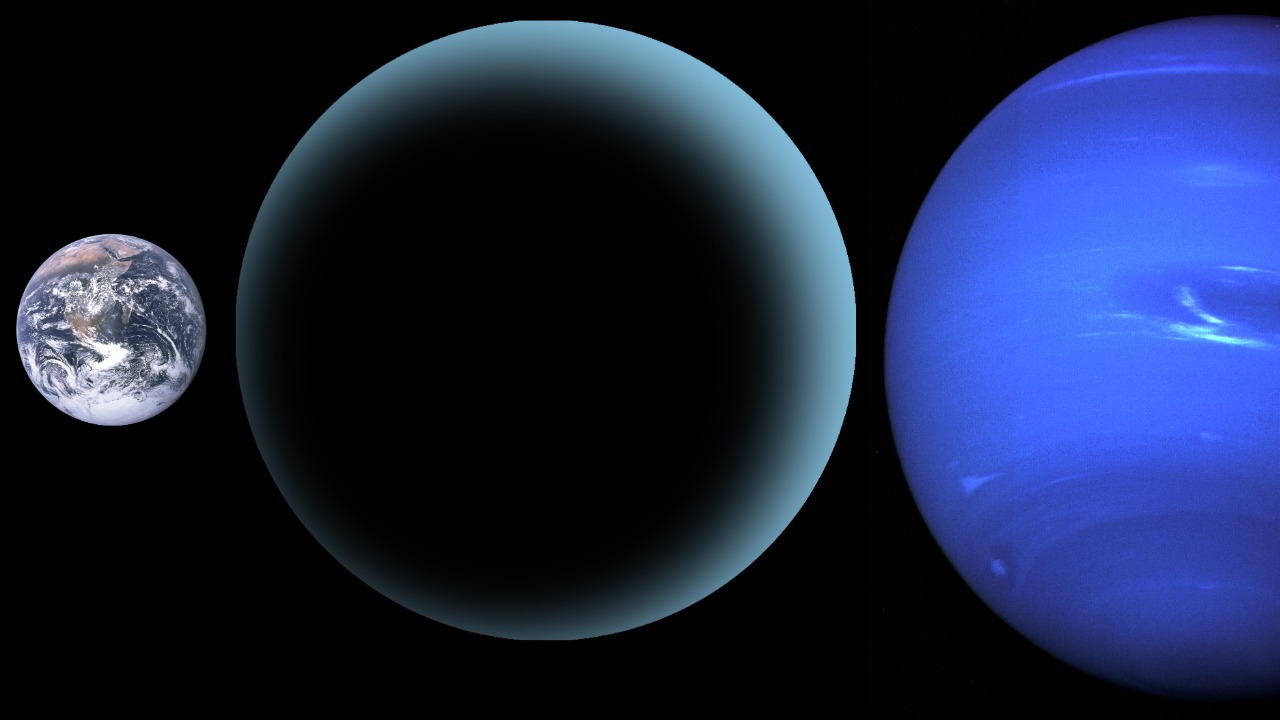

Batygin and Brown’s 2016 simulations in The Astronomical Journal converged on a surprisingly specific mass range for Planet 9, between 5 and 10 times that of Earth. A body this size would be smaller than Uranus and Neptune but far more massive than any known dwarf planet, placing it in the category of a so-called “super-Earth.” The researchers showed that only an object with roughly this mass could shepherd the observed eTNOs into their clustered configuration without destabilizing the rest of the Solar System.

Follow-up analyses of the same dynamical problem have generally supported a similar mass window, reinforcing the idea that Planet 9, if real, is neither a tiny rock nor a full-fledged gas giant. The proposed mass also fits with suggestions that Planet Nine might be the stripped core of a giant planet that was ejected from its original orbit. For planetary formation theories, confirming such an object would provide a rare, tangible example of how violent early Solar System evolution could have been.

3. Orbital Path Spans 400–800 AU

The same 2016 Caltech study predicted that Planet 9 travels on a vast, elongated orbit with a semi-major axis between about 400 and 800 astronomical units. One astronomical unit is the Earth–Sun distance, so at its average distance this hypothetical planet would sit hundreds of times farther out than Earth, deep in the outer Solar System. Such a stretched path would explain why the planet has remained unseen in previous surveys, spending most of its time faint and slow against the background stars.

On their dedicated project site, Batygin and Brown describe how this distant orbit emerged from their numerical models of the eTNOs’ behavior, with different runs favoring slightly different semi-major axes within that 400–800 AU band. The sheer scale of this predicted orbit means that even a large planet would reflect very little sunlight, making it a formidable observational target. For observers planning searches, the orbital range defines a huge volume of sky that must be methodically combed, raising the possibility that Planet 9 is real yet still hiding in plain sight.

4. Six eTNOs Show Clustered Orbits

The core evidence for Planet 9 is the strange behavior of at least six extreme trans-Neptunian objects, including Sedna and 2012 VP113, whose orbits appear to point in roughly the same direction in space. Batygin and Brown noticed that these distant bodies share similar arguments of perihelion and orbital orientations, a pattern that should quickly disperse if left to random gravitational nudges. Instead, the alignment persists, hinting at the steady tug of a massive, unseen companion.

Subsequent discussions of these six small bodies in the outer Solar System have emphasized how anomalous their orbits look compared with standard models of Kuiper Belt dynamics. Analyses of the six objects argue that the gravitational anomalies Brown and Batygin identified are difficult to reproduce without invoking an additional planet. If the clustering is genuine, it would be one of the clearest indirect signatures of a new world, turning these icy remnants into signposts for a hidden giant.

5. Tilted Orbit at 15–25 Degrees

Planet 9 is not only distant, it is also predicted to be tilted. In their 2016 simulations, Batygin and Brown found that the planet’s orbital plane likely sits about 15 to 25 degrees away from the ecliptic, the relatively flat plane traced by most major planets. This inclination helps the model reproduce the three-dimensional distribution of eTNO orbits, not just their clustering in longitude. A modest tilt also offers a way to explain why Planet 9 has escaped detection in surveys that focused near the ecliptic.

By placing the planet on an inclined path, the simulations suggest that its gravitational influence could subtly warp the outer Solar System, potentially contributing to the tilt of the Sun’s spin axis relative to the planetary plane. Discussions of gravitational anomalies in the distant Kuiper Belt often highlight this inclination as a key parameter. For observers, the predicted tilt broadens the search area into higher latitudes, complicating survey strategies but also offering a clear test of the model’s geometry.

6. Subaru Telescope Scans 10% of Sky

Turning theory into observation, Mike Brown and collaborators have used the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii to hunt directly for Planet 9. By 2021, Brown reported that Subaru had covered about 10 percent of the predicted orbital volume where the planet might reside. This search focuses on deep, wide-field imaging of the outer Solar System, looking for a slowly moving point of light that matches the expected brightness and motion of a distant, massive body.

Brown’s updates describe the effort as a kind of celestial hide and seek, with each observing run ruling out more of the sky. The limited coverage so far underscores how challenging the task is, even with one of the world’s most powerful optical telescopes. For the Planet 9 hypothesis, Subaru’s partial survey cuts into the allowed parameter space, gradually tightening constraints on where, and even whether, the planet can exist.

7. Primordial Black Hole Alternative Emerges

Not all researchers agree that Planet 9 must be a conventional planet. In 2023, Amir Siraj and Abraham Loeb Abbott proposed that the inferred mass and orbit could instead belong to a primordial black hole with 5 to 10 Earth masses. Their Physical Review Letters study argued that such a compact object, perhaps only grapefruit-sized, could have been captured by the Solar System early in its history. Gravitationally, it would mimic a planet while remaining optically invisible.

Related work from Harvard scientists outlined how to test whether Planet Nine is a primordial black hole, including searches for flares from dark matter or small bodies being disrupted near it. Online discussions of the hypothesis highlight both its boldness and its difficulty to verify. If correct, the idea would transform Planet 9 from a missing world into a rare window on early-universe physics, raising the stakes of the search far beyond planetary science.

8. Vera Rubin Observatory Poised for 2025 Hunt

The upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile is widely expected to be a game changer for the Planet 9 search. Set to begin operations in 2025, Rubin will image the entire southern sky every few nights, building a deep, time-lapse map of moving objects. Its Legacy Survey of Space and Time will be especially sensitive to faint, slow-moving bodies in the outer Solar System, exactly the regime where Planet 9 should appear if it exists.

Project plans describe how Rubin’s cadence and depth will allow astronomers to track countless trans-Neptunian objects and potentially pick out the subtle motion of a distant planet. For proponents of Planet Nine, the observatory represents the best near-term opportunity to confirm or refute the hypothesis. A detection would instantly settle the debate in favor of an epic discovery, while a null result over several years would push many researchers toward alternative explanations.

9. No Detection Yet Fuels 2024 Debate

As of 2024, no telescope has directly detected Planet 9, and that absence is sharpening the scientific debate. A recent review in Nature Astronomy notes that the orbital clustering of eTNOs could arise from observational bias, with surveys preferentially finding objects in certain regions of the sky. If the data set is skewed, the apparent pattern might fade as more distant bodies are discovered, weakening the case for an undiscovered planet.

At the same time, advocates such as Batygin and Brown argue that newer discoveries still fit the Planet 9 framework, suggesting the signal is real. Others point to analyses by Brown and Batygin that refine the planet’s parameters rather than discard it. Until surveys like Rubin deliver a decisive answer, Planet 9 will remain suspended between epic discovery and cosmic illusion, a reminder of how frontier science often lives in the space between data and doubt.

More from Morning Overview