Physicists are no longer content to simply listen to ripples in spacetime. A new proposal sketches out how an exquisitely tuned laser experiment could, in principle, nudge gravitational waves themselves, turning a once passive form of astronomy into an active laboratory for gravity. If it works, the technique would mark the first controlled interaction between light and gravity at the quantum level and open a path toward steering these waves the way radio engineers shape electromagnetic signals.

The idea builds on a decade of breakthroughs in gravitational wave detection and pushes them into far more ambitious territory. Instead of just catching the faint tremors from distant black holes, researchers now want to amplify, redirect, and even generate gravitational waves inside an interferometer, using the same kind of precision optics that made the first detections possible.

From Einstein’s prediction to a new kind of astronomy

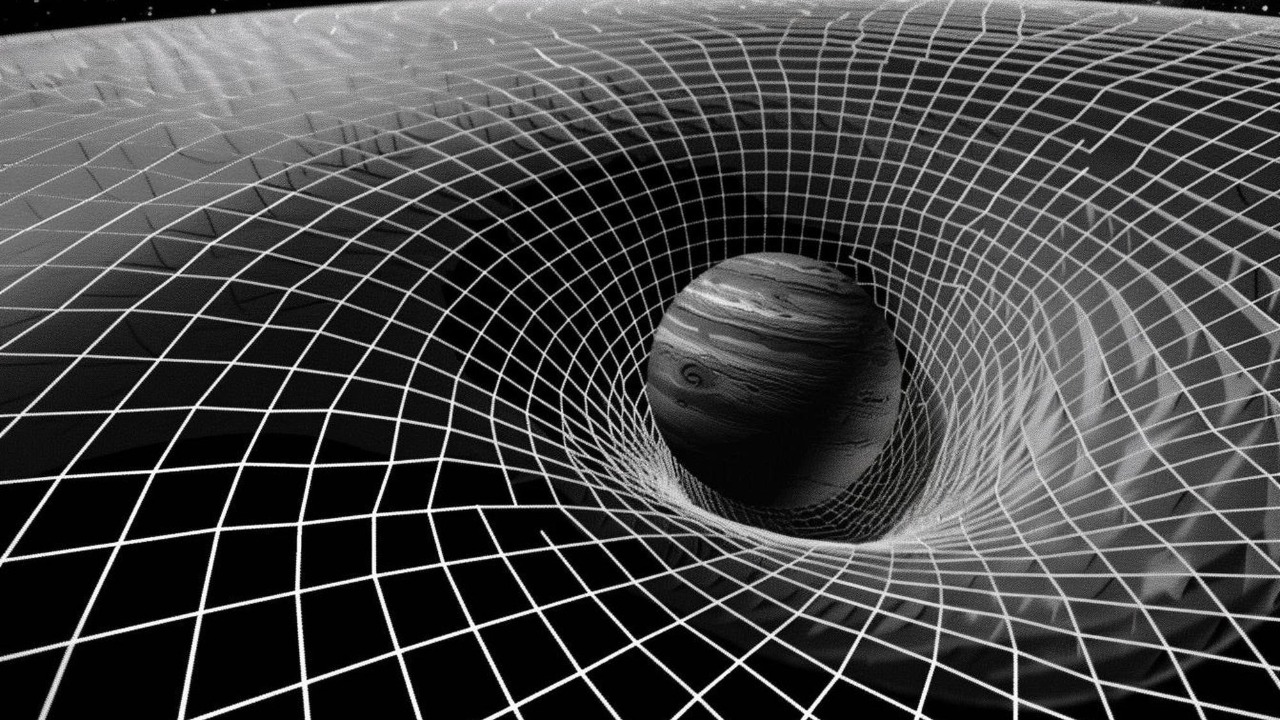

When I look at this new proposal, I see it as the latest chapter in a story that began when Einstein wrote down the Theory of General Relativity and predicted that accelerating masses would send waves through spacetime. For a century those waves were a theoretical curiosity, but the framework they emerged from has become the backbone of modern cosmology and astrophysics. The prediction that gravity itself could carry information, not just pull on objects, set the stage for a radically different way of observing the universe once technology caught up.

That technological leap arrived with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational, Wave Observatory, better known as LIGO, which uses kilometer-scale laser arms to sense distortions thousands of times smaller than a proton. On September 14, 2015, scientists at LIGO recorded the first unmistakable signal from merging black holes a billion light years away, a moment that turned a mathematical prediction into a working tool of observation and effectively launched gravitational wave astronomy as a new field, as later recounted in a retrospective on a decade of gravitational waves.

The first detections and what they unlocked

The first direct detection did more than confirm Einstein’s equations, it proved that exquisitely engineered interferometers could read out the violent dynamics of distant black holes from tiny changes in laser phase. In that initial event, the signal was so clean that one researcher described the data as “Magnificently in alignment” with the predictions of general relativity, a phrase that captured how closely the measured waveform matched the expected pattern of a gravitational wave passing by the instrument, as detailed in an early account of the first detection. That level of agreement gave physicists confidence that they were not just seeing noise or some unknown systematic effect.

The human impact of that moment was captured in a now famous announcement in which a scientist declared, “Ladies and gentlemen. we have detected gravitational waves We did. it. I am so pleased,” during a public briefing that has since been widely shared in a video. Another widely viewed explainer framed the discovery as scientists having “just invented an entirely new way of observing the universe” that does not rely on light, emphasizing that what had been detected were ripples in spacetime itself, as popularized in a separate overview. Those early communications helped cement the idea that gravitational waves were not just a niche curiosity but a foundational new probe of the cosmos.

How interferometers made gravity visible

At the heart of this revolution is a deceptively simple optical layout: a beam splitter sends a laser down two perpendicular arms, and the returning light recombines to reveal tiny changes in path length. In the new proposal to control gravitational waves, the same basic architecture is used, with a beam splitter dividing a laser beam onto both arms of the detector so that passing waves change the interference pattern and, crucially, allow the light field to feed energy back into the gravitational disturbance, as described in a technical summary of how a beam splitter divides the light. The same configuration that made detection possible becomes, in this vision, a two way channel between photons and spacetime curvature.

Existing facilities already demonstrate how far this approach can go. LIGO consists of two identical interferometers located in the United States, one in Livingston, Louisiana, and another in Hanford, Washington, a dual site design that lets scientists distinguish real signals from local disturbances, as outlined in a technical review that labels the facility as 1.1 LIGO. A separate analysis of the field’s early years notes that the recent detection of gravitational waves by the LIGO, VIRGO team was hailed as an incredibly impressive achievement of experimental physics and a major success of the theory of General Relativity, underscoring how these interferometers have already validated Einstein’s framework at a new level of precision, as recounted in a university briefing.

From listening to shaping: the Schützhold proposal

The leap from listening to shaping comes from an idea that treats the interferometer not just as a passive microphone for spacetime but as an active medium where light and gravity exchange energy. In the concept put forward by Prof. Ralf Schützhold, the optical paths inside the interferometer are tailored so that the laser field can stimulate the emission or absorption of gravitons, the hypothetical quantum particles of the gravitational field, effectively allowing the apparatus to manipulate the amplitude of an incoming wave. A detailed news report describes this as an Interferometer Experiment Could Manipulate and Measure Gravitational Waves Prof Ralf Sch, highlighting that the same setup would both sense and steer the signal.Another analysis of the scheme frames it as a “Proposed Experiment: Manipulating Gravitational Waves Prof. Ralf Sch,” emphasizing that the goal is not only to observe but to manipulate gravitational waves by carefully engineering the optical path so that energy can be transferred between the light field and the spacetime ripple, as explained in a feature on the Proposed Experiment. A complementary technical note stresses that in an interferometer tailored to Schützhold’s idea, it could be possible not only to observe gravitational waves but also to amplify or damp them by stimulated emission and absorption of gravitons, directly tying the design to the quantum nature of gravity, as summarized in a report on Sch.

Why gravitons and quantum gravity sit at the center

At the conceptual core of this experiment is the graviton, the hypothetical quantum of the gravitational field that would play a role analogous to the photon in electromagnetism. Planetary dynamics already constrain how heavy such a particle could be, because any mass would subtly alter how gravity falls off with distance; one detailed analysis notes that the motions of the planets have been used to make the best estimate yet of the upper limit of the mass of the graviton, treating it as a quantum of the gravitational field and using orbital data to bound its properties, as discussed in a chapter on the motions of the planets. Those constraints still leave room for a massless or nearly massless graviton, which is exactly the regime where an interferometer based on light could interact with it efficiently.

Quantum field theory provides the language for why such an interaction is even plausible. According to one widely cited explanation, “According to quantum field theory, forces are mediated by exchange particles (photons for electromagnetism, gluons for the strong force, W and Z bosons for the weak force),” and in that same discussion gravitons are proposed to be massless particles that mediate gravity, which would allow them to travel at the speed of light and interact with other fields in a way that can be captured in a quantum description, as summarized in a community discussion that begins with the word According. The Schützhold proposal effectively tries to turn that abstract picture into a concrete experiment, using laser light as a handle on the gravitational field’s quanta.

The mechanics of steering spacetime with light

In practical terms, the proposed setup treats the interferometer as a medium where light and gravity can exchange energy in a controlled way. A detailed description of the design explains that a beam splitter divides a laser beam onto both arms of the detector, and as the light circulates, incoming gravitational waves modulate the optical phase while the intense laser field can in turn feed back into the wave, potentially enhancing or suppressing it and increasing the sensitivity of the interferometer further, as laid out in a technical overview of how a beam splitter divides the light. The key is to tune the optical cavity so that the interaction is resonant, much like how a laser cavity amplifies photons at a specific frequency.

Another report on the same concept emphasizes that in an interferometer tailored to Schützhold’s idea, it could be possible not only to observe gravitational waves but also to amplify or damp them by stimulated emission and absorption of gravitons, effectively turning the device into a gravitational wave laser or attenuator depending on how it is configured, as described in a summary focused on an interferometer tailored to Schützhold’s idea. In that picture, steering spacetime becomes a matter of engineering the right optical environment so that gravitons are more likely to be emitted or absorbed in a particular direction or phase, a radical extension of techniques already familiar from quantum optics.

High frequency waves and laboratory generation

One of the most intriguing aspects of this line of work is the possibility of generating high frequency gravitational waves in the lab rather than waiting for rare astrophysical events. A detailed theoretical study notes that it should be noted that it is possible to carry out laboratory experiments on generation of high-frequency gravitational radiation using optical methods, for example by using intense laser beams and nonlinear media instead of a magnetic field, which opens a path to tabletop sources of gravitational radiation, as argued in a paper on high-frequency gravitational waves generation. If such sources can be combined with sensitive interferometers, researchers could probe regimes of gravity that are inaccessible to current observatories tuned to lower frequencies.

In that context, the Schützhold style interferometer becomes more than a detector, it becomes part of a closed experimental loop where light generates gravitational waves that are then manipulated and measured by the same optical system. A news feature on the broader concept of energy transfer between gravitational waves and light describes how an interferometer tailored to Schützhold’s idea could enable not only observation but also amplification or damping of waves by stimulated emission and absorption of gravitons, effectively turning the apparatus into a laboratory for the quantum nature of gravity, as highlighted in a report on laser light and the quantum nature of gravity. That kind of closed loop experiment would be a major step beyond current observatories, which only receive waves produced far away.

What steering waves could reveal about the universe

If physicists can learn to shape gravitational waves, the scientific payoff could extend far beyond a proof of principle. One immediate application would be to probe the gravitational wave background, the diffuse hum of signals from countless distant sources that Astrophysicists have already begun to characterize using pulsar timing arrays, with one set of studies offering the first direct evidence of a background likely produced by the merging of two black holes across cosmic history, as reported in a summary that notes how Astrophysicists present first evidence of gravitational wave ‘background’. Being able to selectively amplify or filter parts of that background in a controlled experiment could reveal subtle features that are otherwise buried in noise.

Gravitational waves are also emerging as a tool to study dark matter, and active control could sharpen that probe. A recent study on Dark Matter Spikes and Detectable Imprints describes how dense concentrations of dark matter around black holes can leave characteristic signatures in the gravitational waves they emit, and frames this research as an essential step toward a larger scientific effort to use these signals to peer into the fundamental nature of dark matter, as detailed in a report on Dark Matter Spikes and Detectable Imprints. If an interferometer could selectively enhance or suppress certain frequency components of a wave, it might help isolate those imprints and turn gravitational wave signals into precision tools for mapping dark matter environments.

Where this fits in the next decades of gravitational physics

Seen against the broader roadmap for gravitational wave science, the idea of steering waves with light looks less like a wild outlier and more like a natural next step. A comprehensive review of the field notes that the 100 years since the publication of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity have seen a progression from purely theoretical work to indirect evidence and finally to direct detection, and argues that the most exciting discoveries are still to come from upcoming instruments that will push sensitivity and frequency coverage much further, as summarized in an Abstract on gravitational-wave physics and astronomy in the 2020s and 2030s. An experiment that actively couples light and gravity would fit squarely into that trajectory by turning detectors into laboratories.

Educational resources already frame gravitational wave astronomy as a young field with enormous room to grow. One widely used teaching guide explains Why It is Important that Einstein’s prediction has been confirmed, noting that with the first detections a new kind of astronomy has been born, gravitational wave astronomy, which complements traditional observations based on light and particles, as laid out in a resource titled Why It. The Schützhold style proposal suggests that the next phase of that field may not just be about building bigger and quieter detectors, but about learning to sculpt spacetime ripples themselves, using the same laser technology that first let us hear them.

More from MorningOverview