High energy physics and oncology are converging in an unexpected place: the “waste” streams of particle accelerators and nuclear facilities. Instead of treating leftover radiation and spent materials as a disposal problem, researchers are learning how to harvest them as a source of rare isotopes that can precisely attack tumors from the inside.

By turning what used to be a liability into a medical asset, scientists are sketching out a future in which the same machines that probe the structure of matter also quietly manufacture cancer therapies. The shift could ease chronic shortages of key isotopes, cut costs, and tie the next generation of cancer drugs to the infrastructure of big physics and Nuclear power.

From wasted radiation to a medical resource

I see the core breakthrough as a change in mindset: instead of letting unused radiation dissipate into shielding and cooling systems, researchers are designing ways to capture it in carefully chosen targets. High energy accelerators already generate intense beams that slam into experimental apparatus, and a significant fraction of that Energy is not used for the primary physics measurements. By inserting additional materials in the right locations, teams can convert that surplus into medically useful isotopes rather than letting it vanish as heat and background noise, a shift that recent work on accelerator “waste” has started to document in detail.

The same logic applies to nuclear facilities that have historically focused on power generation or weapons material. For decades, reactors optimized their fuel cycles around uranium 235 and 239, treating many byproducts as long term waste to be isolated and stored. Now, chemists and engineers are revisiting those inventories with a different lens, asking which nuclides could be separated and repurposed as feedstock for cancer drugs. The result is a growing toolkit of methods that treat radiation not as an unavoidable hazard but as a raw material for targeted therapies.

Why Copper-67 is suddenly in the spotlight

Among the isotopes emerging from this rethink, Copper-67 has become a star. Iodine and lutetium have long dominated discussions of radiopharmaceuticals, yet Copper-67 offers a combination of beta emissions for killing cancer cells and gamma rays that can be imaged, which makes it attractive for so called “theranostic” drugs that both diagnose and treat disease. Researchers behind a recent accelerator study describe how Copper-67 emits radiation that can be tuned to damage tumors while sparing surrounding tissue, and they argue that this dual role could make it a workhorse for future oncology if supply constraints can be solved, a case laid out in detail in a report on Copper-67.

The bottleneck has never been scientific interest, it has been production. Traditional routes to Copper-67 rely on specialized reactors or dedicated cyclotrons that can only generate modest quantities, which keeps prices high and discourages large clinical trials. The accelerator waste approach flips that equation by piggybacking on facilities that already run at enormous power for fundamental physics. In one study, the team summarized its philosophy with a simple line, noting that “Our method lets high-energy accelerators support cancer medicine while continuing their core scientific work,” a sentiment echoed in a separate submission that highlights how Our Copper strategy could scale without disrupting existing experiments.

How scientists mine particle accelerators for isotopes

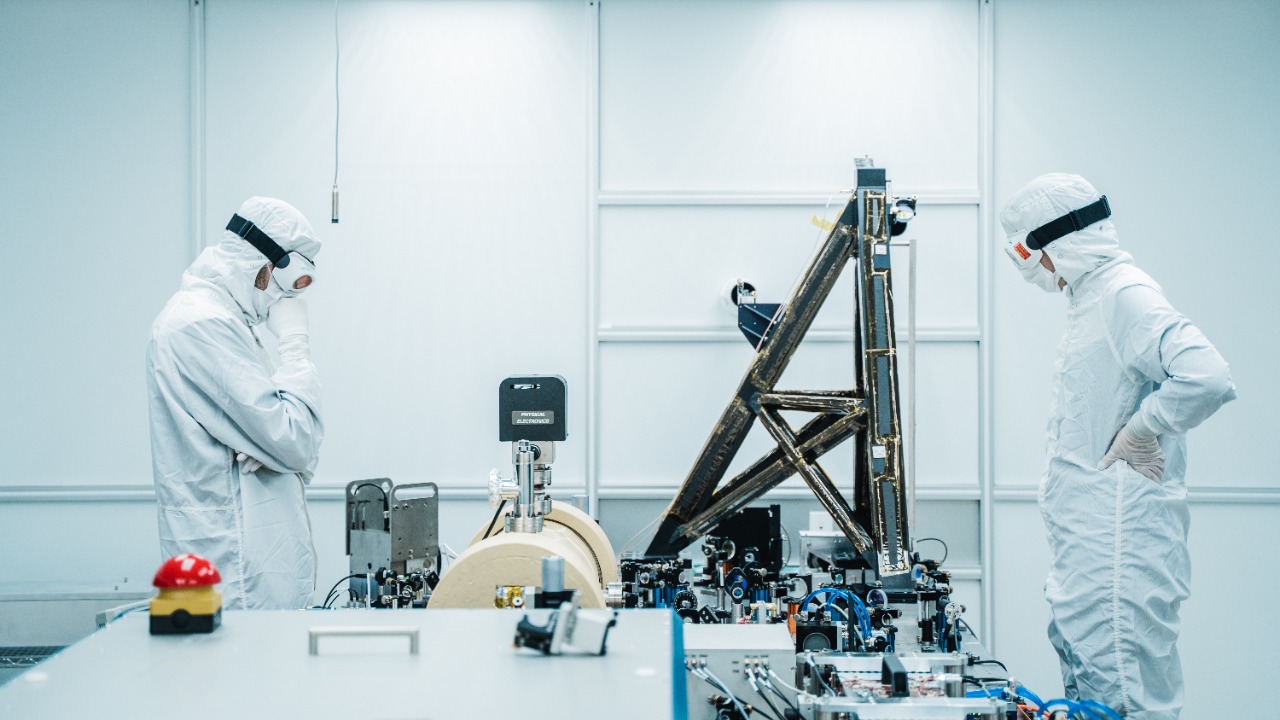

Turning a physics machine into a medical isotope factory is not as simple as bolting on a new pipe. I have watched researchers describe a careful choreography in which thin foils or liquid targets are placed where stray neutrons and secondary particles are most intense, but still compatible with the accelerator’s primary mission. The goal is to expose these materials to enough radiation to transmute their nuclei into isotopes like Copper-67, then remove and process them without contaminating the rest of the facility. Reports on accelerator waste emphasize that the beams used to probe subatomic particles can simultaneously drive nuclear reactions in these targets, effectively stacking two scientific outputs on the same infrastructure.

One detailed account explains how Scientists have found a way to convert high energy radiation waste from particle accelerators into a critically scarce cancer fighting isotope, describing how careful placement of targets and shielding allows the capture of useful nuclides while keeping the main beamline stable. The same report notes that Copper-67 demand far outstrips current supply because these isotopes are not abundant in nature and are difficult to produce in bulk, a gap that the new method aims to close by harnessing radiation that would otherwise be discarded, as outlined in coverage of how Scientists convert accelerator waste.

Inside the new accelerator-waste study

At the heart of the latest excitement is a specific proposal to retrofit high energy accelerators with copper based collectors. I read the study’s description of how thin copper components, already present in many beamline elements, can be engineered to accumulate Copper-67 as they are bombarded by stray particles. Instead of treating these components as disposable hardware that slowly degrades, the researchers suggest cycling them out on a schedule, then chemically extracting the newly formed isotope for medical use. The approach effectively turns routine maintenance into a production line for cancer drugs, without demanding new beam time or major redesigns.

The team behind this work stresses that their concept is compatible with existing research programs, which is crucial for winning over facilities that guard every minute of accelerator operation. They argue that by carefully modeling the radiation fields and optimizing the geometry of copper parts, they can maximize isotope yield while keeping the physics experiments untouched. A detailed news report on this work notes that the intense beams of particles inside accelerators, typically focused on unlocking the deepest secrets of the universe, can also be harnessed to generate the materials necessary for cancer treatment, a dual role highlighted in coverage of how Nov researchers tap accelerator waste.

From lab concept to clinical supply chain

Even the most elegant physics side project has to survive contact with the medical supply chain. I see three hurdles that will determine whether accelerator waste isotopes make it from whiteboard sketches to hospital pharmacies: regulatory approval, logistics, and economics. Regulators will want to know that isotopes produced in high energy environments meet purity standards and can be traced from target to patient, which means facilities must build robust quality control and documentation into their extraction processes. Logistics teams will need to coordinate rapid transport, because many therapeutic isotopes have half lives measured in hours or days, leaving little margin for delays between production and infusion.

Economically, the promise lies in using infrastructure that is already funded for other purposes. A report on how Particle accelerator waste could help produce cancer fighting materials notes that energy that would normally go to waste in these machines can be redirected into isotope production, effectively spreading the fixed costs of accelerators across both physics and medicine. If that model holds, it could lower the price of therapies that rely on scarce nuclides, making them more accessible to hospitals that cannot afford bespoke production facilities, a prospect underscored in coverage of how Particle energy is repurposed.

Nuclear power’s parallel push into cancer care

While accelerators grab headlines, nuclear plants and legacy stockpiles are quietly becoming another front in the isotope revolution. I have watched Nuclear power company TerraPower and Energy Department contractor AtkinsRealis Isotek describe how they are extracting a key component for a promising cancer treatment called targeted alpha therapy from material that once sat in secure storage. Their process involves carefully separating specific isotopes from a complex mix of nuclear byproducts, then purifying them to the standards required for human use, a transformation that turns a long term liability into a medical asset.

This work sits alongside a broader reevaluation of how nuclear infrastructure can serve medicine. One report explains how the transition to nuclear power may lead to a major breakthrough in cancer treatment, with journalist Ashley Webster visiting Oakidg to examine how reactors and associated facilities can be tuned to generate therapeutic isotopes alongside electricity. In that coverage, the focus is on how a new generation of plants and research reactors could be designed from the ground up with dual missions, supplying both grid power and medical nuclides, a vision that comes through in the segment featuring Ashley Webster in Oakidg.

Reimagining nuclear waste as a drug factory

The idea of turning nuclear waste into medicine can sound like science fiction, yet the underlying chemistry is straightforward. Spent fuel and legacy materials contain a zoo of isotopes, some of which emit the alpha or beta particles that oncologists prize for their ability to shred cancer cells at close range. I have seen researchers explain that most nuclear reactors historically focused on managing uranium 235 and plutonium 239 for power and weapons, leaving many of these byproducts unexploited. By revisiting those inventories with modern separation techniques, they can isolate nuclides that are ideal for targeted alpha therapy and other advanced treatments, a strategy laid out in a detailed explainer on Nuclear waste transformed into therapy.

Another account walks through how most nuclear reactors concern themselves with two different forms of regular elements, uranium 235 and plutonium 239, but notes that the same neutron rich environment that drives fission also creates a host of medically relevant isotopes. In that narrative, the challenge is not physics but policy and investment: facilities must decide to fund the hot cells, chemical plants, and transport networks needed to move from raw waste to pharmaceutical grade products. The video that explores Turning Nuclear Waste Into Cancer Drugs makes this point explicitly, highlighting how a shift in priorities could unlock a steady stream of therapeutic nuclides from materials that are already on site, a case that hinges on rethinking the role of Apr era nuclear waste.

What this means for patients and the future of oncology

For patients, the stakes are straightforward: more isotopes mean more options. Many of the most promising radiopharmaceuticals have been constrained not by clinical science but by the difficulty of securing enough material for large trials and routine care. If accelerator waste and nuclear byproducts can reliably supply isotopes like Copper-67 and the alpha emitters used in targeted alpha therapy, oncologists will be able to match drugs more precisely to tumor types and patient biology. That could accelerate the shift toward theranostic regimens in which the same molecule that lights up a tumor on a scan also delivers the killing blow, tightening the feedback loop between diagnosis and treatment.

There are still open questions about how quickly these production methods can scale and how regulators will oversee facilities that straddle the line between physics lab, power plant, and pharmaceutical factory. Yet the direction of travel is clear in the reporting from Nov on accelerator waste and in the accounts of TerraPower and Isotek’s work with the Energy Department. I see a future in which high energy accelerators, nuclear reactors, and even legacy stockpiles are woven into a distributed network of isotope sources, each turning what used to be a disposal headache into a lifeline for people facing cancer, a vision that is already taking shape in detailed coverage of how Nov accelerator work feeds medicine.

More from MorningOverview