Earth is not warming in a neat, even gradient. While the planet as a whole continues to heat up, one vast swath of the globe is bleeding internal heat into space much faster than the other, creating a deep planetary imbalance that stretches from the core to the climate system. The result is a world where the interior is cooling asymmetrically even as the atmosphere warms, a combination that reshapes everything from ocean currents to long term geological evolution.

Scientists are now tracing this split to the way continents and oceans are arranged, the legacy of ancient supercontinents, and the physics of how heat escapes from deep inside the planet. I see a story that connects the Pacific hemisphere’s rapid cooling, the Atlantic side’s relative insulation, and the reality that global warming is still accelerating, even as Earth’s interior slowly loses energy.

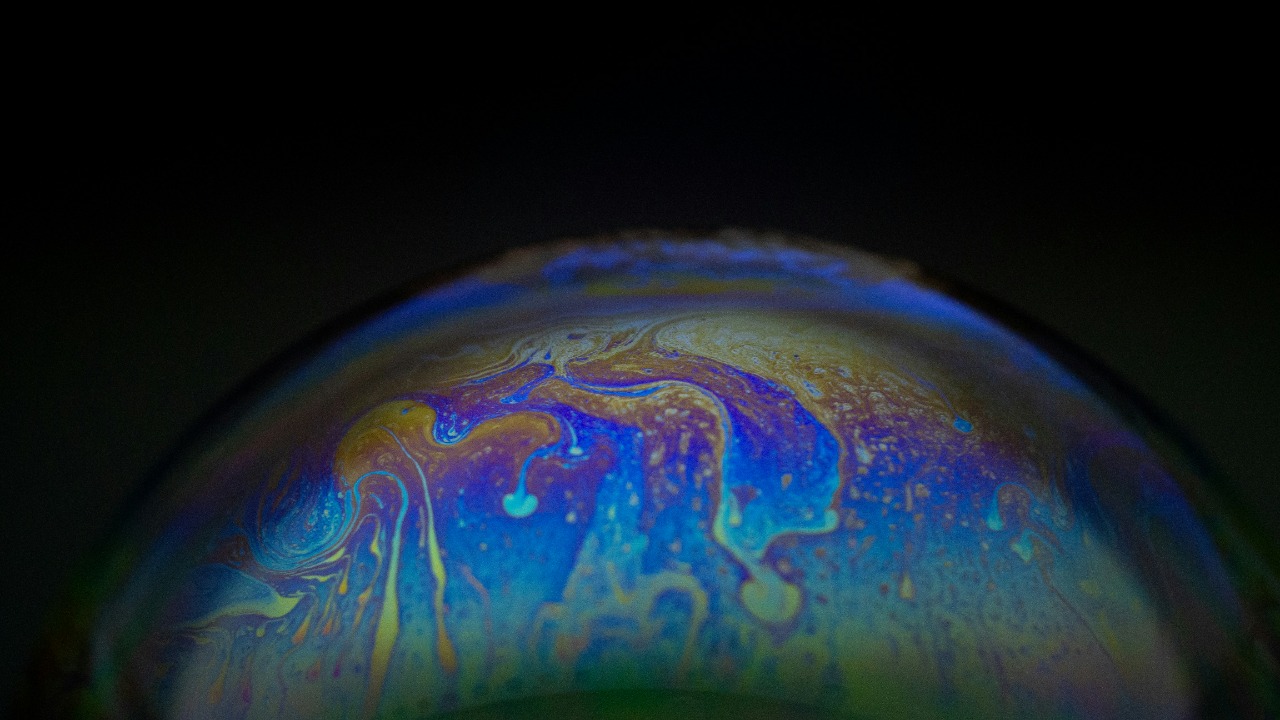

The strange reality of an unevenly cooling planet

When researchers say one side of Earth is cooling faster, they are not talking about the weather outside your window. They are describing how the planet’s interior heat leaks into space more efficiently beneath one hemisphere than the other, a process that unfolds over tens of millions of years. Recent Research shows that the Pacific hemisphere is losing heat far more quickly than the side dominated by Africa, Europe, and Asia, creating a planetary lopsidedness that is invisible in daily forecasts but profound in geophysical terms.

In practical terms, this means the mantle and crust beneath the Pacific are acting like a more efficient radiator, while the opposite side behaves more like a thick blanket. I see that contrast as the key to understanding why one half of the globe is cooling its interior faster, even as human driven greenhouse gas emissions push surface temperatures higher. The asymmetry does not contradict global warming, it operates on a different layer of the planet and a different timescale.

Why the Pacific hemisphere is losing heat so quickly

The Pacific side of Earth is dominated by oceanic crust, which is thinner and denser than the bulky continents that cluster on the opposite hemisphere. That thinner crust allows more internal heat to escape, especially along long chains of mid ocean ridges and subduction zones that ring the Pacific basin. According to detailed Interestingly described modeling, less heat is lost beneath the hemisphere that carries Africa, Europe, and Asia, while the Pacific hemisphere sheds more of its internal energy into space.

Over geological time, that imbalance can subtly reshape mantle convection, the slow churning of hot rock that drives plate tectonics. I read the Pacific hemisphere’s rapid cooling as a sign that its tectonic plates, riddled with subduction zones, are acting like conveyor belts that pull heat upward and vent it through volcanism and seafloor spreading. The continental hemisphere, by contrast, behaves more like a lid, with thick crust that insulates the mantle below and slows the escape of heat.

How ancient supercontinents set up today’s imbalance

The current split between a Pacific dominated hemisphere and a continent heavy side is not an accident of the present day. It is the legacy of deep time, when landmasses repeatedly merged into supercontinents and then broke apart. Earlier configurations, such as Pangaea, concentrated thick continental crust on one side of the globe, leaving a vast ocean on the other, and that pattern still echoes in the way heat escapes today. The same Pacific hemisphere that now cools faster can be traced back through plate reconstructions to those ancient arrangements.

When I look at that history, I see a planet whose thermal evolution is inseparable from its tectonic story. Thick continental blocks that once clustered together still act as insulators, while the oceanic basins that wrapped around them remain efficient pathways for heat loss. The asymmetry in cooling is therefore not a short term quirk but a structural feature of Earth’s crust and mantle, built up over hundreds of millions of years of continental collisions and rifts.

Global warming is still accelerating, even on a lopsided Earth

The fact that one hemisphere is losing internal heat faster does not mean the planet is getting colder overall. At the surface, the dominant signal is the accumulation of greenhouse gases, which trap outgoing infrared radiation and drive up global temperatures. Climate records compiled from land stations, ocean buoys, and satellites show that global surface temperatures have risen sharply, and analysis of long term trends confirms that Global Warming Is Global, with Earth continuing to warm despite year to year fluctuations.

In that context, the interior cooling asymmetry is a background process, not a counterargument to climate change. I see it as a reminder that Earth’s energy budget has multiple layers: heat from the core and mantle leaks out slowly, while human emissions alter the balance of incoming and outgoing radiation at the top of the atmosphere much more quickly. The Pacific hemisphere can cool its interior faster while the atmosphere above both hemispheres warms, and the data show that is exactly what is happening.

Different hemispheres, different climate patterns

Even within the warming atmosphere, the two halves of the planet do not respond in identical ways. Both Northern and Southern hemispheres are heating up with global warming, but scientists see differences in climate patterns between them, from the distribution of land and ocean to the behavior of storm tracks and sea ice. Reporting on paleoclimate and modern observations notes that Both Northern and Southern hemispheres have experienced distinct climate histories, yet both are now locked into a warming trend driven by greenhouse gases.

I read those hemispheric contrasts as a surface level echo of the deeper thermal imbalance. The Northern Hemisphere, with its larger land area and dense human infrastructure, tends to show faster warming in surface air temperatures, while the Southern Hemisphere’s vast oceans absorb and redistribute more heat. Yet, despite these differences, the underlying physics of greenhouse forcing ensures that both sides of the equator are gaining energy in the climate system, even as the solid Earth beneath them slowly loses internal heat.

From mantle plumes to “snowball Earth” scares

Uneven cooling inside the planet has consequences that go far beyond abstract heat flow diagrams. Variations in how and where heat escapes can influence mantle plumes, volcanic activity, and the long term cycling of carbon between the interior and the atmosphere. Some geophysical analyses argue that, although no unifying model explains all of the observed thermal fluctuations of Earth, we now know that there have been major cooling events in the past when the planet lost interior heat rapidly enough to reshape its climate, raising the question of whether Although Earth could drive itself toward a “snowball” state.

From my perspective, those deep time episodes highlight how sensitive the climate can be to slow shifts in internal heat loss and volcanic outgassing. When the balance tips toward less volcanic carbon dioxide and more efficient cooling, global temperatures can plunge over millions of years. Today’s situation is the mirror image: human emissions are overwhelming those slow geological controls, pushing temperatures up rapidly even as the mantle continues its gradual cooling, especially beneath the Pacific hemisphere.

What this split means for future climate and geology

Projecting forward, the asymmetry in interior cooling is likely to keep shaping plate motions, volcanic hotspots, and the eventual assembly of future supercontinents. A faster cooling Pacific hemisphere could see changes in subduction dynamics and seafloor spreading rates, which in turn affect sea level and the distribution of continents over tens of millions of years. I see that as a reminder that the map of the world is not fixed, and that the current arrangement of a vast Pacific basin opposite a cluster of continents is only one chapter in a long tectonic cycle.

For the climate system, the more immediate stakes lie in how ocean basins and continents steer currents and winds. The existing contrast between a deep, heat shedding Pacific and a continent heavy hemisphere that stores more heat in land and shallow seas will continue to influence patterns like El Niño, monsoons, and midlatitude storms. While those patterns play out on human timescales, they are ultimately framed by the slow, uneven cooling of the planet beneath our feet.

Reconciling a cooling interior with a warming world

At first glance, it can sound contradictory to say that one side of Earth is cooling fast while the other warms. The key is to separate the layers of the system and the timescales involved. The Pacific hemisphere’s rapid loss of internal heat is a deep Earth process that unfolds over millions of years, governed by plate tectonics and mantle convection. The warming that dominates headlines is a surface phenomenon, driven by greenhouse gases that have accumulated in just a few human generations.

When I put those pieces together, I see a planet that is both aging and overheating. Its core and mantle are gradually losing the primordial and radioactive heat that once made early Earth more like a young, volcanically active world, while its atmosphere is gaining energy from human activity at a pace that dwarfs natural changes. The uneven cooling of the interior does not rescue us from climate change, but it does shape the stage on which that crisis unfolds, from the layout of continents to the behavior of the oceans that absorb much of the excess heat.

More from MorningOverview