Nvidia’s chief executive has started describing the refusal to adopt artificial intelligence as a kind of corporate self-harm, arguing that any leader who ignores the technology is effectively choosing to fall behind. His message is not a gentle suggestion to experiment with new tools but a blunt warning that AI is now a prerequisite for staying competitive in almost every industry.

I see his stance as less about hyping the next big thing and more about drawing a line between organizations that will treat AI as basic infrastructure and those that will be left optimizing yesterday’s workflows. The question is no longer whether AI will reshape work, but how quickly companies and workers are willing to reorganize around it.

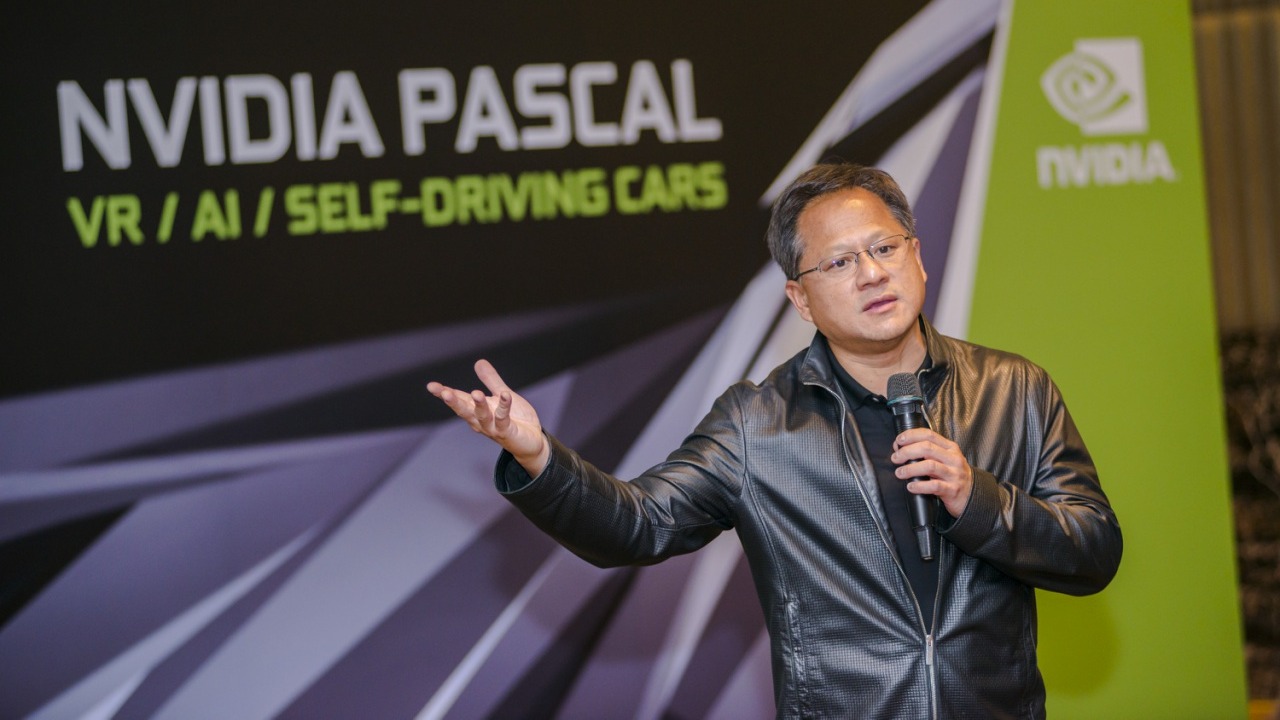

Huang’s “insane” warning and what he actually meant

When Jensen Huang calls it “insane” not to go all in on AI, he is not just talking about buying more chips, he is arguing that leaders who delay are making an irrational bet against the direction of computing itself. In his view, AI is becoming the default way software is written, data is analyzed, and products are designed, so opting out is like refusing to use the internet in the 2000s or mobile in the 2010s. That framing turns AI from a discretionary innovation project into a baseline requirement for survival, especially for companies that depend on software, logistics, or data-heavy decision making.

His comments, reported in detail in a recent interview and echoed in an industry brief, are explicit about the stakes: he argues that organizations that do not aggressively integrate AI into their operations will be outcompeted by those that do. I read that as a statement about compounding advantages, because once a company starts using AI to automate routine work, personalize products, and accelerate R&D, it can reinvest those gains into even more ambitious systems. The gap between early adopters and laggards then widens with each product cycle, which is why Huang frames hesitation as a kind of strategic madness rather than a cautious wait-and-see approach.

Inside Nvidia’s own AI-first culture

Huang’s rhetoric would ring hollow if Nvidia were not applying the same pressure internally, but the company’s own culture shows how far he expects employees to lean into automation. In a leaked internal message, he urged staff to use AI tools far more aggressively in their day-to-day work, from coding and documentation to design and support. The underlying message is that if a task can be accelerated or improved by a model, it should be, and that employees are expected to treat AI as a default collaborator rather than an optional add-on.

Reporting on that internal push describes how he told Nvidia workers not to worry about their jobs being replaced if they embraced these tools, but to worry instead if they did not, a stance captured in coverage of his guidance to employees and in a detailed account of his AI-first expectations. I see that as a clear articulation of the new psychological contract inside AI-heavy firms: security comes not from doing a narrow task that can be automated, but from showing you can orchestrate and extend what the automation can do. In that environment, the most valued people are not those who resist AI, but those who figure out how to combine it with domain expertise to ship better work faster.

How his message landed with workers and the wider internet

Huang’s insistence that employees saturate their workflows with AI has spilled well beyond Nvidia’s walls, sparking a mix of admiration, anxiety, and skepticism among workers in tech and beyond. Some see his stance as a rare moment of candor from a CEO who is willing to say out loud that the only safe place in an AI-driven economy is on the side of those building and wielding the tools. Others hear a familiar corporate refrain that urges staff to embrace automation while leaving open the question of who ultimately benefits from the productivity gains.

That tension shows up in the way his remarks have been shared and debated across social platforms. A widely circulated post summarizing his reassurance that workers should not fear AI if they use it has drawn comments from people who welcome the clarity and from those who worry it normalizes constant upskilling pressure. On developer forums, a long thread in one programming community captures that split, with some engineers agreeing that ignoring AI tools is career malpractice and others arguing that not every role or company can realistically “go all in” at the same pace. I read that reaction as evidence that while Huang’s message resonates with those already steeped in AI, it also exposes a growing divide between workers who feel empowered by these tools and those who feel cornered by them.

The viral clips that turned a strategy into a slogan

Part of why Huang’s warning has broken out of niche industry circles is that it translates neatly into short, shareable clips that travel well on video platforms. In one widely viewed segment, he leans into the idea that refusing to adopt AI is effectively choosing to be left behind, delivering the line with the kind of bluntness that makes for instant reposts. The format strips away nuance but amplifies the core message: in his view, AI is not a side project, it is the main event.

That dynamic is clear in a short video that condenses his argument into a few seconds of soundbite-ready urgency, and in a longer conference appearance where he lays out why he thinks every company will eventually be an AI company. I see those clips as doing double duty: they serve Nvidia’s commercial interest by reinforcing the idea that demand for AI infrastructure is inevitable, and they also crystallize a broader shift in executive communication. Instead of couching transformation in cautious language, leaders like Huang are increasingly willing to speak in absolutes, betting that a clear, if polarizing, message will cut through the noise and rally both investors and early adopters.

Why Huang thinks every industry is now an AI industry

Underneath the provocative language is a straightforward thesis: Huang believes AI is becoming a general-purpose technology that will seep into every sector, from manufacturing and healthcare to media and finance. In that framing, AI is less a discrete product and more a new layer in the computing stack that will sit underneath everything from customer service chatbots to drug discovery pipelines. If that is right, then companies that treat AI as a narrow experiment in one corner of the business will struggle to match competitors that rebuild their core processes around it.

His argument, as summarized in several industry analyses, is that the cost curves and capability curves of AI are moving in opposite directions: models are getting more powerful at the same time as the cost of running them is falling for those who know how to optimize workloads. I interpret that as a warning that the window for gaining an early-mover advantage is open now but will not stay open forever. Once AI-native competitors have used these tools to redesign products, pricing, and operations, late adopters will not just be behind on technology, they will be trapped in older business models that cannot easily absorb the new capabilities.

What “going all in” looks like for companies and workers

For executives, taking Huang’s advice seriously means more than signing a few cloud contracts or piloting a chatbot, it means treating AI as a core competency that touches strategy, hiring, and culture. That can involve building internal platforms so teams can safely experiment with models, retraining managers to think in terms of human plus AI workflows, and reworking metrics so that productivity gains from automation are reinvested rather than simply harvested as short term cost cuts. In practice, it also means accepting a period of messy transition where legacy processes and AI-augmented ones coexist, with uneven results.

For individual workers, “going all in” is less about blind enthusiasm and more about disciplined experimentation with tools that can actually change the way they work. I see three practical moves that align with Huang’s message without surrendering agency. First, identify the repetitive parts of your job that could be offloaded to AI and test tools that target those tasks. Second, invest in understanding how prompts, data quality, and model limitations affect outcomes so you can supervise the systems rather than just consume their output. Third, pay attention to how leaders in your field are talking about AI, whether in formal talks like Huang’s leaked remarks or in more informal channels, because those signals often foreshadow where expectations and opportunities are heading.

The backlash, the hype, and the realistic middle ground

Huang’s absolutist language has inevitably attracted criticism from those who see it as self-serving or out of touch with sectors that face tighter budgets, regulation, or infrastructure constraints. Some skeptics argue that calling it “insane” not to adopt AI ignores legitimate concerns about bias, privacy, and reliability, especially in high stakes domains like healthcare or public services. Others point out that not every organization has the data maturity or technical talent to safely deploy advanced models at scale, and that rushing in can create more risk than value.

At the same time, the enthusiasm around his message has taken on a life of its own in fan communities and on visually driven platforms, where polished edits of his talks circulate as motivational content. A stylized social clip that frames his comments as a call to personal reinvention shows how easily a corporate strategy speech can be repackaged as self-help. I think the healthiest response sits between uncritical hype and blanket rejection: acknowledge that a leader whose company sells the shovels of the AI gold rush has every incentive to talk in extremes, but also recognize that his core point about the direction of travel is hard to dispute. The practical challenge for everyone else is to translate that macro thesis into concrete, measured steps that fit their own risk tolerance, resources, and values, rather than treating “all in” as a one-size-fits-all command.

More from MorningOverview