Warp drive has long been a narrative shortcut for science fiction, but a new generation of physicists is treating it as a serious, if distant, engineering problem. Instead of asking whether faster-than-light travel is “real,” they are quietly reframing the question around how spacetime itself might be shaped, powered, and measured with tools that already exist in modern laboratories.

The result is a subtle but important shift: warp concepts are moving from pure fantasy toward testable models, even if practical starships remain far beyond reach. I see the emerging picture as less about building a star cruiser tomorrow and more about learning how to bend the cosmic fabric in controlled ways today.

The sci‑fi idea that refuses to die

For decades, warp drive has been shorthand for impossible speed, a plot device that lets crews in shows like “Star Trek” hop between star systems in a single episode. The core idea is simple enough: instead of pushing a ship through space, you reshape spacetime around it so that the craft effectively rides a wave of compressed and expanded space. In this picture, nothing locally breaks the light-speed limit, yet the overall journey outpaces any conventional rocket.

Physicists have increasingly pointed out that spacetime is not a rigid backdrop but a dynamic medium that already stretches and ripples, from the expansion of the universe to gravitational waves. That recognition has encouraged some researchers to treat the fictional “warp bubble” as a specialized configuration of general relativity rather than pure magic, a perspective echoed in recent discussions of how spacetime is being warped constantly by massive objects and cosmic expansion.

From Alcubierre’s math to modern warp bubbles

The modern scientific conversation about warp drive traces back to Mexican theoretical physicist Miguel Alcubierre, who in the 1990s wrote down a solution to Einstein’s equations that appeared to allow a “warp bubble” to move faster than light relative to distant observers. His Alcubierre Drive did not accelerate a ship in the usual sense, it contracted space in front of the bubble and expanded it behind, leaving the craft itself in free fall inside a locally calm region. On paper, the math worked, which was enough to ignite decades of speculation.

The catch was brutal: Alcubierre’s original configuration demanded “exotic” negative energy densities that have never been observed in the real universe at usable scales. Later work has tried to tame that requirement, and some recent models argue that carefully shaped positive energy distributions might mimic parts of the effect, a line of reasoning that underpins new claims that warp drives may actually be possible someday without invoking unphysical matter. Those proposals remain highly idealized, but they mark a shift from “never” to “maybe, under extreme conditions.”

NASA’s early flirtation with warp field mechanics

Long before social media seized on every warp headline, a small group inside NASA began quietly probing whether the Alcubierre idea could be translated into laboratory-scale experiments. One widely cited internal study, titled “Warp Field Mechanics 101,” set out to review the original Alcubierre paper and explore how a warp field might work in principle. The document, archived on the NASA Technical Reports Server, framed the problem as a blend of general relativity, field theory, and engineering constraints, and it treated warp not as a near-term project but as a long-range thought experiment grounded in real equations.

That same work is also accessible through a focused excerpt on the NTRS NASA Technical Reports Server Field Mechanics 101 page, which walks through how the Alcubi solution might be interpreted in engineering language. The tone is cautious, but the mere existence of such a document inside NASA signaled that warp concepts had graduated from convention-panel speculation to at least a niche corner of institutional research, even if the work stayed firmly on the theoretical side.

Harold White, interferometers, and the first lab probes

The most visible champion of practical warp studies inside NASA has been Harold “Sonny” White, who helped popularize the idea that clever geometry might drastically reduce the energy needed for a warp bubble. In public talks and technical notes, he has argued that reshaping the bubble into a toroidal ring could lower the required energy from absurd cosmic scales to something merely astronomical. A detailed interview on interstellar travel describes how Dr. White is currently running the White–Juday warp-field interferometer experiment as a proof of concept, using precision optics to hunt for tiny distortions in spacetime that might hint at controllable warp-like effects.

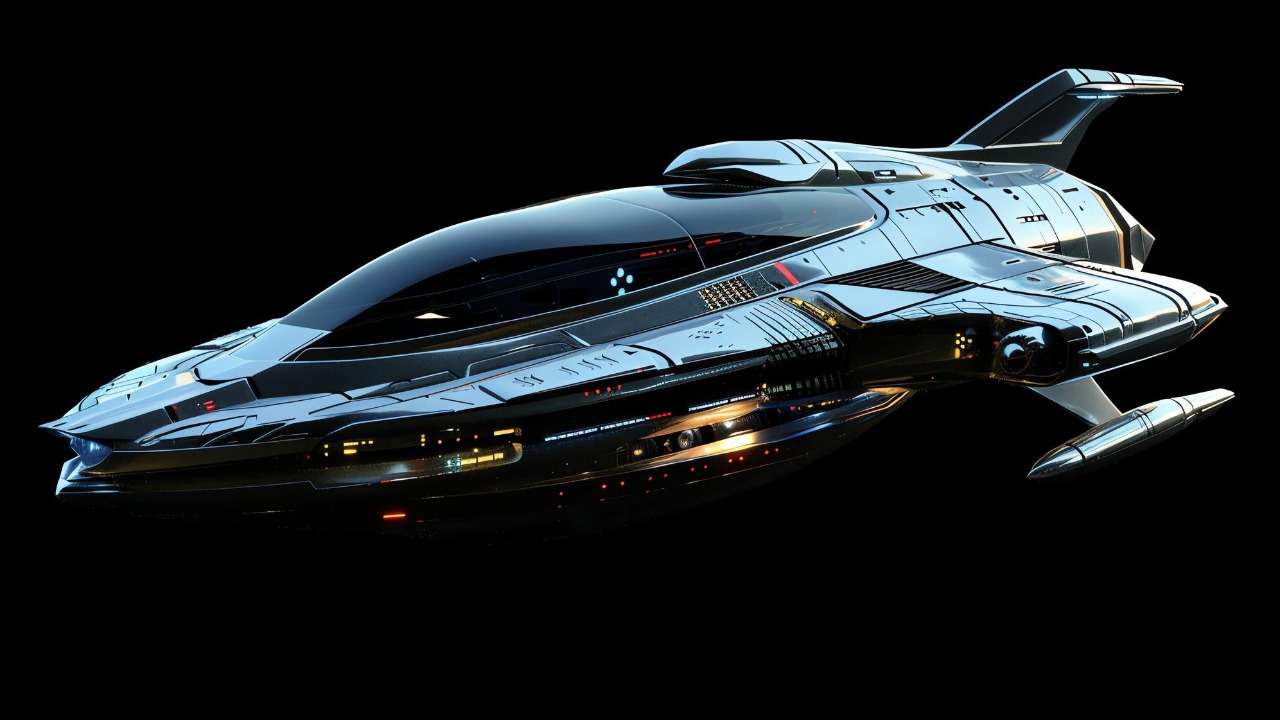

White’s work also spilled into the public imagination through concept art and media coverage of a sleek warp-capable starship. A widely shared feature on a speculative design explained how a NASA physicist reimagined a warp-speed spaceship with a ring-shaped drive that wrapped around a central crew module, explicitly inspired by the Alcubierre Drive. Those images were never blueprints, but they helped crystallize the idea that warp research could be framed in terms of concrete hardware, not just abstract tensors.

New models that ditch negative energy (on paper)

More recently, independent theorists have tried to sidestep the most notorious obstacle in Alcubierre’s proposal: the need for negative energy. A research group operating under the name Applied Physics has argued that certain warp configurations might be constructed entirely from known forms of matter and energy, at least in principle. Their analysis suggests that a carefully engineered shell of positive energy density could generate a modest spacetime distortion, a claim summarized in a report that notes how, However, thanks to some new research by Applied Physics, a warp drive using known physics might well be possible after all.

Popular explainers have amplified that message, sometimes with breathless framing that glosses over the fine print. One widely shared video, for instance, leans into the idea that warp drive is no longer just science fiction and describes it as a real though distant scientific possibility, while still acknowledging that the effect is no longer stuck in the first, purely speculative stage. The underlying math remains highly idealized, and the energy requirements are still staggering, but the shift from exotic to positive energy in the equations is a genuine conceptual advance that narrows the gap between fantasy and physics, at least on the chalkboard.

Why many physicists still say warp “breaks” physics

For every optimistic warp headline, there is a chorus of skeptics pointing out that the underlying proposals strain or outright violate key principles of relativity and quantum field theory. Critics argue that even if the equations admit a warp-like solution, the conditions required to assemble and sustain such a configuration would destabilize under quantum effects or demand impossible control over matter and energy. A detailed breakdown of these objections is captured in a long-form explainer on why warp drive breaks the laws of physics, which walks through issues like causality, energy conditions, and the tendency of faster-than-light constructs to invite paradoxes.

Some of the sharpest pushback comes from within the scientific community itself, where researchers bristle at media pieces that oversell incremental theoretical work as a “breakthrough.” In one widely circulated discussion thread, a physicist bluntly calls a popular article “a terrible article that warps what the actual paper says” and stresses that the proposed configuration still requires exotic matter and is not remotely possible with current technology, especially when it comes to the energy needed to create the folding described in the model, a critique preserved in the singularity forum discussion. That tension between sober theory and sensational coverage is likely to persist as long as warp remains a powerful cultural metaphor.

The brutal energy bill: from Jupiter to the cosmos

Even in the most optimistic models, the energy bill for a meaningful warp bubble is staggering. Early estimates for the Alcubierre Drive called for more energy than existed in the observable universe, a figure that later refinements trimmed down but never to anything remotely practical. Popular science communicators have leaned into that absurdity to make the point vivid, with one viral explainer joking that if you want to power a warp drive, you will just need to convert the entire planet of Jupiter into energy, which is presented as an “Easy” step only in the most tongue-in-cheek sense.

More serious analyses tie warp energy demands to the same dark energy that appears to be causing the universe’s accelerated expansion. Some of the recent positive-energy warp concepts explicitly reference the cosmological constant as a template for how spacetime can be driven to expand, and they suggest that any practical warp system would need to manipulate similar forms of vacuum energy on command, a notion that underpins claims that the universe’s accelerated expansion offers a hint of what a warp engine would have to harness. Until physics delivers a way to tap and shape that energy with precision, the gulf between theoretical warp bubbles and real engines will remain enormous.

Lessons from NASA’s wind tunnels and real-world testbeds

One way to understand where warp research stands is to compare it with earlier eras of aerospace experimentation. Before supersonic flight became routine, engineers spent years building scale models and blasting them with air in massive facilities to map out shock waves and structural loads. NASA’s own history is full of such infrastructure, including the 30 x 60-Foot Full Scale Tunnel, also known as Building 643, which was used to test full-size aircraft and other vehicles. Archival material invites readers to Search the NASA Technical Reports Server for additional examples of the historic research conducted in this facility, underscoring how methodical experimentation paved the way for technologies that once seemed outlandish.

Warp research has not yet reached the wind-tunnel stage, but the analogy is instructive. The White–Juday interferometer and similar tabletop experiments are the warp equivalent of early smoke-tunnel tests, crude but essential steps toward understanding how fields behave under controlled conditions. The existence of formal studies like Warp Field Mechanics 101 shows that at least some institutions are willing to treat warp as a legitimate topic for structured inquiry, even if the practical payoff lies far beyond any current mission plan.

Public fascination, Oct videos, and the culture of warp

Warp drive’s grip on the imagination is not just a matter of equations, it is also a cultural phenomenon that thrives on videos, explainers, and debates that blur the line between education and entertainment. In recent months, creators have released detailed breakdowns of why warp concepts remain controversial, including a long-form piece uploaded in Oct that walks viewers through the ways faster-than-light travel appears to clash with relativity. Another widely shared video, also posted in Oct, leans into the idea that warp drive is no longer stuck in the first stage of speculation and frames it as a real though distant scientific possibility, complete with animations of spacetime bubbles sliding through the cosmos.

Short-form platforms have joined in as well, with creators on TikTok using humor to highlight the absurd energy scales involved and to poke fun at the idea that converting Jupiter into fuel is a casual engineering task. One such clip, posted in Oct, riffs on the phrase “Well, you’ll just need to convert the entire planet of Jupiter into energy. Easy!” to drive home the point that the gap between theory and practice is still vast. This ecosystem of explainers, from Patreon-supported deep dives to quick-hit jokes, keeps warp in the public conversation and ensures that each new paper is instantly refracted through a mix of enthusiasm and skepticism.

Why incremental warp research still matters

Even if no one alive today ever boards a warp-capable starship, the incremental research around spacetime engineering could reshape other parts of physics and technology. Efforts to design precise interferometers for warp experiments, for instance, feed directly into broader work on gravitational wave detection and ultra-stable optical systems. The same mathematical tools used to analyze warp bubbles also apply to cosmology, black hole physics, and the study of how quantum fields behave in curved spacetime, areas where new insights can ripple outward into everything from GPS corrections to fundamental tests of relativity.

There is also a psychological value in keeping a few audacious goals on the horizon. When a NASA physicist shares a sleek warp starship concept or when a group like Applied Physics publishes a model that trims away exotic matter, they are not promising a working engine so much as staking out a frontier where theory and imagination can meet. The real engineering may unfold over centuries, but the conceptual groundwork is being laid now, in papers, lab benches, and even in the spirited arguments that erupt whenever someone claims warp has finally arrived.

More from MorningOverview