Fusion researchers have long known that powerful magnets are the key to turning star-like reactions into a practical power source, and the latest generation of “super magnets” is starting to look less like a lab curiosity and more like grid-scale hardware. By pushing magnetic fields to unprecedented strengths while shrinking the footprint of the machines that generate them, engineers are edging closer to fusion devices that could realistically plug into existing energy systems rather than sit forever in the realm of experiments.

The new technology is not a single gadget but a convergence of high-field superconducting coils, advanced manufacturing and AI-driven control, all aimed at trapping ultra-hot plasma efficiently enough to produce net electricity. If these magnets perform in full-scale reactors the way they are beginning to perform in test stands, they could mark the point where fusion shifts from a scientific milestone to an engineering race.

Why magnets sit at the heart of fusion’s next leap

Magnetic confinement is the central engineering challenge for fusion power because the fuel must be heated to temperatures hotter than the core of the Sun without touching any solid surface. In tokamak and stellarator designs, doughnut-shaped coils create a magnetic bottle that keeps the plasma suspended, and the stronger and more precisely shaped that field is, the smaller and more efficient the reactor can become. That is why so much of the current momentum in fusion is focused not on the plasma itself, but on the magnets that hold it in place.

High-field magnets promise a double benefit: they can raise the pressure of the plasma, which boosts the fusion reaction rate, and they can shrink the overall size of the machine, which cuts cost and complexity. Recent projects have zeroed in on superconducting materials that can carry enormous currents with minimal losses, allowing devices to reach field strengths that would have been impractical with older copper coils. As these designs move from concept to hardware, the magnet systems are starting to look like the decisive lever for making fusion plants economically competitive with gas turbines and large solar farms.

The new generation of high-field fusion magnets

One of the most ambitious pushes is coming from compact tokamak developers that are betting on high-temperature superconductors to deliver power-plant scale fields in relatively small devices. In the United Kingdom, engineers have announced a fusion power plant magnet technology breakthrough that is explicitly framed as a step toward commercial reactors, with new high-field coils designed to operate at higher temperatures than traditional low-temperature superconductors and to fit inside a more compact tokamak geometry, as described in their detailed update on fusion power plant magnet technology. The goal is to combine strong confinement with manufacturability so that magnets can be produced in series rather than as one-off scientific instruments.

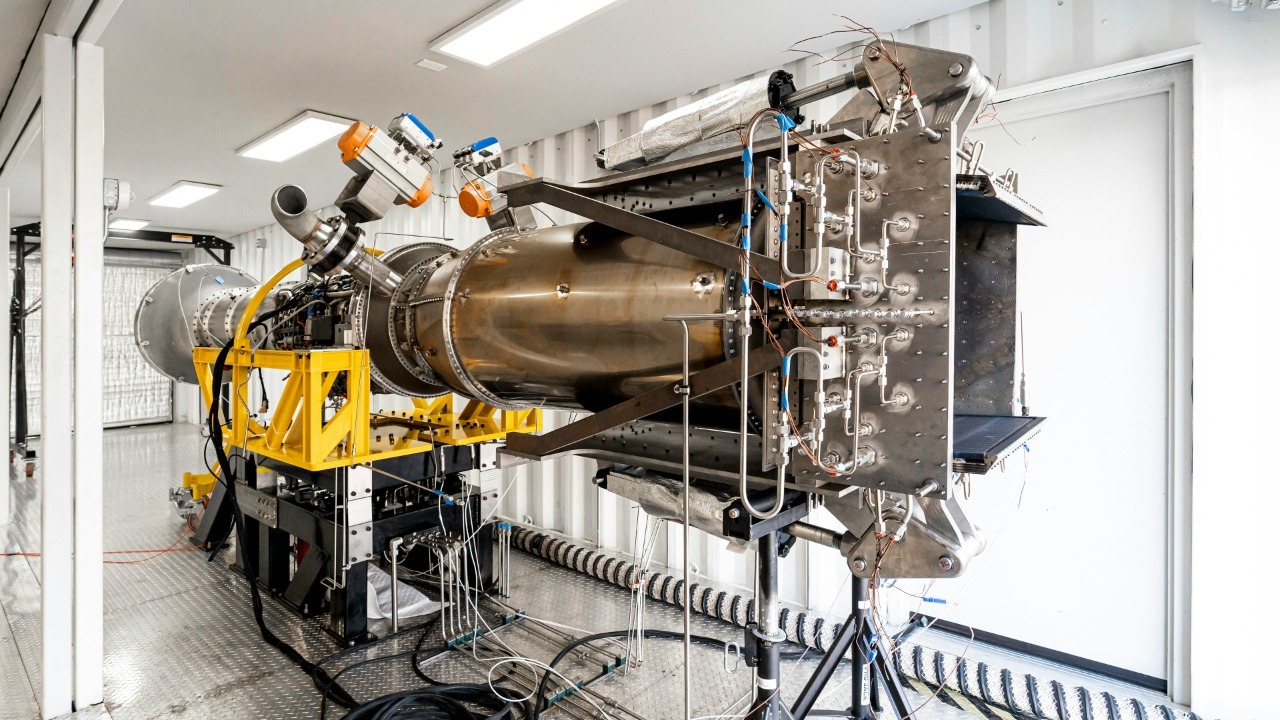

That same company has been building and testing full-scale superconductor modules that are intended to mirror the conditions inside a future power plant, rather than just a physics experiment. Its program to construct and qualify super magnets for fusion plant testing focuses on stress management, quench protection and integration with cryogenic systems, all of which are essential if the coils are to run reliably for years at a time instead of a few experimental pulses. The effort to validate these components under realistic loads is documented in its work on super magnets for fusion plant testing, which underscores how magnet engineering is now being treated as a product development challenge rather than a purely scientific one.

Record-setting pulsed magnets and the race for scale

While compact devices chase continuous operation with high-temperature superconductors, other teams are pushing the limits of pulsed magnetic fields to explore how far confinement can be driven in large-scale experiments. In San Diego, General Atomics has completed what it describes as the world’s largest and most powerful pulsed superconducting magnet for fusion energy, a system built to generate extremely strong fields for short durations so researchers can probe plasma behavior at conditions relevant to future reactors. The company’s announcement on the world’s largest pulsed superconducting magnet highlights the sheer scale of the device, which is designed to integrate with major fusion facilities and test how high-field operation affects stability and performance.

Local reporting has emphasized that this magnet is not just a technical showpiece but a potential enabler for “limitless clean energy,” since it can help validate the physics and engineering assumptions behind next-generation reactors. By delivering very high magnetic fields in a controlled, repeatable way, the system allows scientists to explore regimes that would otherwise be out of reach, tightening the link between theory and machine design. Coverage of the project’s potential impact on future reactors and the broader energy landscape is captured in analysis of the General Atomics magnet, which frames it as a bridge between today’s experimental devices and tomorrow’s power plants.

From ITER-scale coils to compact super magnets

The global fusion community has already seen what it takes to build magnets at the scale of ITER, the international tokamak under construction in southern France, where massive superconducting electromagnets are central to the design. These coils, some of which weigh hundreds of tons, are engineered to generate fields strong enough to confine a 150 million degree Celsius plasma in a device the size of a small office building. Reporting on the project’s magnet systems has detailed how the nuclear fusion electromagnets for ITER rely on low-temperature superconductors cooled with liquid helium, and how their complexity has driven both cost and schedule, as explored in coverage of the nuclear fusion electromagnet work.

In parallel, smaller companies and research groups are trying to capture ITER-class performance in far more compact packages by switching to high-temperature superconductors and novel coil geometries. One detailed look at this trend describes how a new fusion energy super magnet is being positioned as a route to net fusion energy in devices that could fit on industrial sites rather than sprawling campuses, with the magnet’s higher operating temperature and field strength enabling a much smaller tokamak for the same output. That vision of shrinking the machine while preserving performance is at the heart of reporting on a fusion energy super magnet, which casts the technology as a way to leapfrog the scale and cost constraints that have dogged earlier projects.

AI, control systems and the role of software

Hardware alone will not make these super magnets useful if operators cannot control the plasma they confine, and that is where AI is starting to play a more visible role. Researchers have begun training machine learning systems to predict and shape plasma behavior in real time, using data from existing tokamaks to teach algorithms how to avoid instabilities that could damage the magnets or shut down the reaction. One prominent collaboration has described how reinforcement learning agents can design and maintain complex plasma shapes that would be difficult to manage with traditional control schemes, an approach detailed in work on bringing AI to the next generation of fusion energy, which shows how software can extend what even the best magnets can achieve.

That research, outlined in the project’s explanation of AI for fusion energy, suggests that smarter control could allow reactors to run closer to their physical limits without sacrificing safety, effectively squeezing more performance out of the same magnetic hardware. By learning to anticipate disruptions and adjust coil currents on the fly, AI controllers could reduce wear on superconducting systems and increase uptime, both of which are crucial for any plant that hopes to sell electricity into competitive markets. In that sense, the new super magnets and the algorithms that manage them are two halves of the same technological shift.

Community scrutiny and public expectations

As with any high-profile fusion advance, the latest magnet breakthroughs have been met with a mix of excitement and skepticism from the broader technical community. Online forums where fusion specialists and enthusiasts gather have dissected claims about “world-first” super magnets, probing the details of field strength, duty cycle and materials to see whether the announcements represent incremental progress or a genuine step change. One widely discussed thread on a fusion-focused community examined a world-first super magnet breakthrough that was billed as a key to practical reactors, with contributors parsing the engineering claims and comparing them to previous high-field demonstrations, as seen in the discussion of a world-first super magnet breakthrough.

That kind of scrutiny is healthy, because it forces developers to back up bold language with hard data and to clarify what has been achieved in the lab versus what remains unproven at reactor scale. It also shapes public expectations, reminding policymakers and investors that even impressive magnet tests are only one piece of a much larger puzzle that includes fuel handling, materials resilience and grid integration. The conversation around these magnets is therefore not just about physics, but about credibility and the pace at which fusion can realistically move from prototype to power plant.

Why this magnet moment matters for fusion’s future

For all the justified caution, the convergence of high-field magnets, AI control and large-scale test hardware marks a real inflection point for fusion energy. Detailed explainers have highlighted how advances in superconducting technology are making it possible to build magnets that are both stronger and more efficient, with one overview of superconducting magnet innovation noting how new materials and designs could slash the size and cost of future reactors while maintaining the extreme fields they require. That perspective is captured in reporting on a next-generation superconducting magnet, which frames the technology as a practical enabler rather than a distant aspiration.

Public-facing videos and explainers are also helping to translate these technical milestones into accessible narratives, showing how specific magnet designs fit into the broader roadmap toward commercial fusion. A widely viewed breakdown of recent fusion magnet progress walks through the engineering behind high-field coils, the role of cryogenics and the way these systems interact with plasma control, giving non-specialists a clearer sense of why magnets are often described as the “unsung heroes” of fusion devices. That kind of communication, exemplified by a detailed fusion magnet explainer, is crucial for building informed support as governments and private investors decide how aggressively to back this technology in the years ahead.

More from MorningOverview