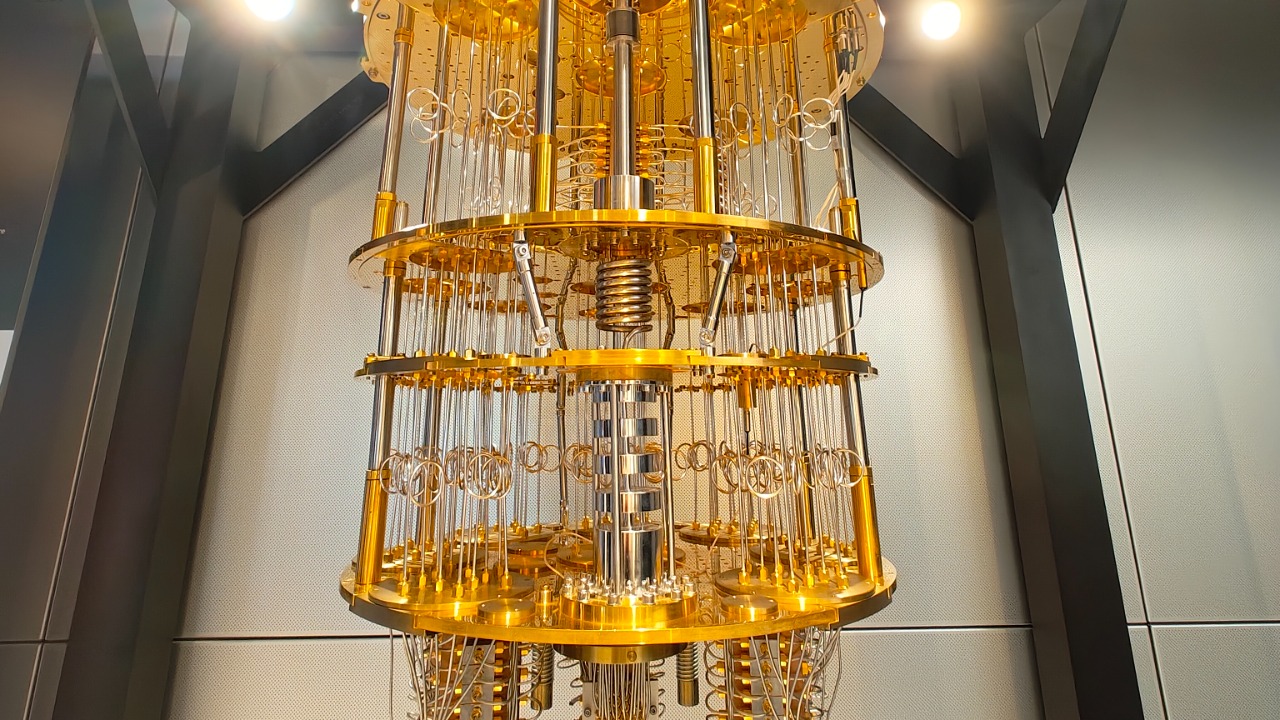

Quantum computing has long been constrained by the messy reality of controlling fragile qubits with bulky, power-hungry hardware. A new generation of laser technologies is starting to change that equation, promising cleaner control, denser architectures, and radically more scalable machines. If these approaches hold up outside the lab, they could turn lasers from a supporting act into the central engine of future quantum processors.

Instead of treating light as a simple on–off switch, researchers are learning to sculpt it with exquisite precision, using it to flip materials into new electronic states, rewrite magnetism, and stabilize vast arrays of atoms. The result is a quiet but profound shift: quantum computing is beginning to look less like a cryogenic wiring nightmare and more like an optical engineering problem.

From lab curiosity to scalable light engines

The most striking sign of this shift is the way entire quantum architectures are being redesigned around light. At Stanford, researchers have demonstrated that carefully structured optical fields can provide the kind of stable, uniform control that large qubit arrays demand, turning photons into the primary “wiring” for a scalable processor. Their work on light-based control suggests that instead of routing thousands of microwave lines into a cryostat, future systems could distribute quantum instructions through integrated photonic networks.

What makes this so consequential is not just the elegance of using light, but the engineering leverage it offers. Optical signals can be multiplexed, split, and routed on chip with far less heat and crosstalk than traditional electronics, which is exactly what dense qubit arrays need. A related line of work, described as having broad implications beyond computing, points to the same conclusion: once light becomes the primary control medium, the bottleneck shifts from cryogenic wiring to optical design, a domain where industry already has decades of experience.

Chip-scale laser control shrinks the hardware problem

Scaling quantum hardware is not just about clever architectures, it is about shrinking the physical devices that generate and tune the light itself. One recent advance compresses a key laser-frequency control system into a chip-scale device that is roughly 100 times smaller than a human hair, yet still offers unprecedented precision. This miniaturized module can sit directly on a quantum processor, trimming away racks of external optics and making it far more realistic to deploy large machines outside national labs.

A complementary effort has produced a microchip-sized device that can rapidly tune laser frequencies with extreme stability, a capability that is essential for addressing individual qubits without disturbing their neighbors. Researchers describe this microchip-sized device as a way to make future quantum computers dramatically more powerful than anything possible today, precisely because it collapses complex optical benches into a form factor compatible with semiconductor manufacturing. In practical terms, that means quantum hardware can start to look less like a physics experiment and more like a server blade.

Lasers as the backbone for 100,000-qubit architectures

The real test of any control technology is whether it can handle truly massive qubit counts. In work led by Sebastian Will, Researchers in the US have developed an extremely powerful laser system explicitly designed to manage a 100,000-qubit machine. Their approach uses light to trap and manipulate individual atoms, each of which can act as a qubit, while maintaining the coherence and uniformity needed for large-scale algorithms. The system is not a commercial computer yet, but it is a concrete blueprint for how lasers could underpin machines that are orders of magnitude larger than today’s prototypes.

What stands out in this architecture is how central optical engineering has become. Instead of wiring up 100,000 control lines, the design relies on carefully shaped beams that can be split, steered, and modulated to reach every atom in the array. A related report on 100,000 qubits underscores that the goal is not just raw qubit count, but a platform that can scale far beyond today’s systems without collapsing under its own complexity. In my view, that is the clearest sign yet that lasers are moving from a supporting role to the structural backbone of quantum hardware.

Flipping materials and rewriting magnetism with ultrafast light

Lasers are not only controlling qubits directly, they are also reshaping the materials that might host future quantum states. At Michigan State University, Shy Cohen and colleagues have shown that a burst of invisible light can flip a material into a different electronic state, effectively changing how it behaves on demand. Their work uses an ultrafast laser pulse to trigger this transformation, demonstrating that burst of invisible can do far more than illuminate a surface, it can reprogram the underlying quantum landscape.

In a related direction, physicists have used light to alter magnetic order in a novel quantum material, effectively rewriting magnetism with carefully tuned pulses. The experiment, described as Laser Light Rewrites in a Breakthrough Quantum Material, shows that magnetism, often treated as a static property, can be dynamically controlled with optical fields. For quantum computing, that opens the door to devices where the very phase of matter can be toggled on demand, allowing engineers to switch between different operating modes or error-protection schemes using nothing more than tailored light pulses.

Borrowing tricks from industrial lasers and femtosecond labs

While these breakthroughs sound exotic, they are increasingly drawing on techniques that have matured in other laser-heavy industries. Modern fabrication lines already rely on ultra-high-speed lasers for cutting and welding, paired with sophisticated software that optimizes beam paths for precision and throughput. The same kind of control logic is now being adapted to quantum hardware, where better precision and over beam shape and timing can translate directly into lower error rates and more reliable qubit operations. In effect, the industrial laser ecosystem is becoming an unintentional supplier of tools and expertise for quantum labs.

Fundamental research is also feeding into this convergence. At Berkeley Lab, scientists have used a femtosecond laser to manipulate quantum states in a way that could help build more scalable processors, showing how Using a femtosecond pulse can create and probe delicate correlations that are otherwise hard to access. Another team has demonstrated a tiny on-chip phase modulator, captured in a Top-down image credited to Andrew Leenheer and described by By Charles, that can precisely control the phase of light interacting with the basic units of quantum information. This Top-down device is a reminder that the path to giant quantum computers may run through surprisingly small pieces of photonic hardware.

More from Morning Overview