Parkinson’s disease has long been defined by the slow, relentless loss of dopamine-producing neurons, with treatments focused on easing symptoms rather than stopping the underlying damage. A new wave of immunotherapies is trying to change that trajectory by training or redirecting the immune system so it stops attacking vulnerable brain cells and, in some cases, actively protects them. The emerging science suggests that shielding neurons from immune-driven injury could slow progression and make future cell-replacement strategies far more durable.

Instead of simply topping up dopamine, researchers are now probing how microglia, antibodies, and engineered cells might interrupt the chain of events that kills neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Early data from animal models and first-in-human trials point to a future in which the brain’s own defenses are carefully rewired, turning a destructive response into a protective shield around still-functional cells.

Why the immune system matters in Parkinson’s neurodegeneration

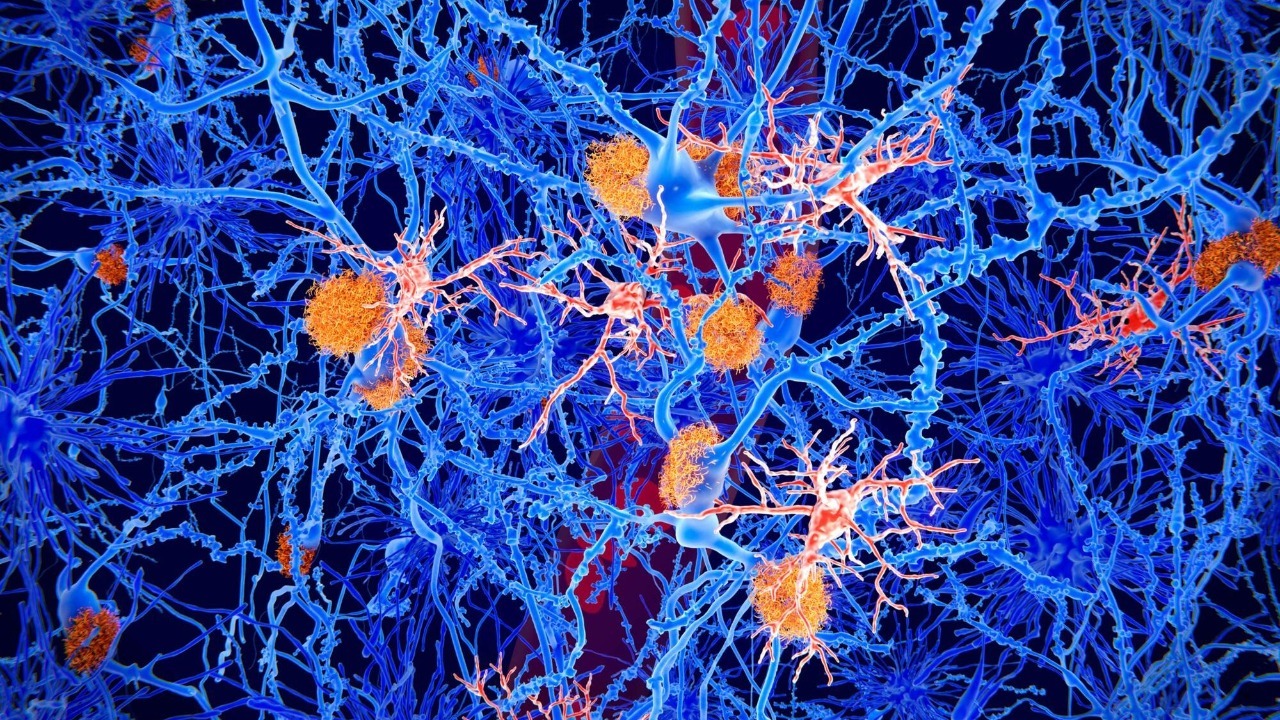

For years, Parkinson’s disease was framed mainly as a problem of misfolded alpha-synuclein and failing dopamine neurons, but the immune system is now firmly in the spotlight. Classic neuropathology work has shown that chronic inflammation, glial activation, and toxic protein buildup are shared features across several neurodegenerative disorders, a pattern summarized in an Abstract that links Parkinson with other conditions that “share common neurodegenerative disease processes.” That convergence has pushed researchers to ask whether immune cells in the brain are simply reacting to damage or actively driving it.

Evidence from broader neurodegeneration research supports the idea that immune-driven mechanisms can be central to neuronal death. Work in Alzheimer’s disease, for example, describes “a number of pathogenic mechanisms triggering the neurodegenerative phenomena and leading to neuronal death,” and stresses that targeting these pathways is essential “in order to stop/slow down the neurodegenerative process,” as detailed in a pharmacology analysis of pathogenic mechanisms. I see Parkinson’s research now borrowing that logic, treating inflammation and immune misfiring not as background noise but as primary targets for intervention.

Microglial “mistaken identity” and a new immunotherapy target

One of the most striking recent ideas comes from work on microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain that act as both sentinels and garbage collectors. In healthy tissue, microglial receptors help identify damaged or dying neurons so they can be cleared away, but in Parkinson’s disease those same receptors appear to be overexpressed and misdirected. Researchers at the Institut de Neurociències of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, or UAB, report that in Parkinson these overexpressed receptors mistakenly identify still-functional neurons as if they were debris, triggering microglia to engulf and destroy them through phagocytosis, a process described in detail in a Feb analysis of regulating microglial phagocytosis.

The same UAB team has proposed an immunotherapy that would block or fine-tune those receptors so microglia stop “eating” viable neurons while still clearing genuinely damaged cells. In preclinical models, antibodies that interfere with this mistaken identity signal appear to prevent microglia from surrounding and digesting dopamine neurons, a mechanism highlighted in a Feb report that explains immunotherapy could prevent of neurons in Parkinson. Another account of the same work notes that this receptor-driven recognition allows microglia to literally “eat” target neurons and emphasizes, with the phrase “What is parti,” how unusual it is to see still-functional cells removed in this way, underscoring why an immunotherapy may halt by interrupting that process.

Vaccine-style and antibody approaches to slow progression

Alongside microglial targeting, researchers are testing more classical immunotherapies that aim to neutralize toxic proteins or recalibrate inflammatory signals. A comprehensive review of Parkinson immunotherapy notes that “With the increasing prevalence of Parkinson’s disease (PD), there is an immediate need to interdict disease signs and symptoms,” and surveys strategies that include active vaccines, passive antibodies, and small molecules that modulate immune pathways, all framed within the broader context of With the need to move beyond symptomatic care. I read that as a clear statement of intent: the field is no longer satisfied with simply smoothing out tremor and rigidity.

One of the most concrete examples is a “vaccine style” treatment that trains the immune system to recognize and clear pathological alpha-synuclein, the protein that clumps inside neurons in Parkinson. Early results from a study of a drug developed by AC Immune, reported by Parkinson’s UK, suggest that participants receiving the immunotherapy over 12 months showed biological signals consistent with slowed disease activity, a finding summarized in coverage of New approaches to slowing Parkinson. Other biotech companies are pursuing similar concepts, with Multiple firms developing antibodies and cellular therapies that, as one overview puts it, could “slow down or even completely stop” disease progression in preclinical models, a sense of optimism captured in a Jun feature that opens with the phrase “But there is hope on the horizon” and details how Multiple immunotherapies are being tested in mice.

Protecting transplanted neurons with an “invisibility cloak”

Even if immunotherapies succeed in slowing neuron loss, many people with advanced Parkinson will still need replacement cells to restore function. That is where cell therapies like Bemdaneprocel enter the picture. Bemdaneprocel is described as a Cell Therapy for PD that uses dopamine neurons derived from stem cells, with the pharmaceutical company Bayer taking what one analysis calls “a much bolder approach to novel therapies in PD,” as outlined in a Jan update on Bemdaneprocel. The promise is straightforward: replace what has been lost with lab-grown neurons that can integrate into the brain’s circuitry.

The challenge is that transplanted cells can be attacked by the recipient’s immune system, even inside the brain. To address that, scientists have engineered human brain cells with an “invisibility cloak” that helps them evade immune detection, allowing them to survive longer and function more effectively after transplantation. In rat models of Parkinson, these engineered Neurons restored motor function and maintained their benefits over time, according to an Apr report that describes how Neurons engineered to evade the immune system could work as cell-replacement therapy. A related account of the same work emphasizes that human Brain cells given this cloak “fix Parkinson’s symptoms in rats,” reinforcing the idea that immune evasion is not a theoretical tweak but a practical way to extend the life of transplanted cells, as detailed in a Nature news story on Brain cells and Parkinson.

Borrowing immune ideas from cancer, diabetes, and other diseases

Parkinson researchers are not inventing immune strategies in a vacuum, they are adapting concepts that have already reshaped cancer and autoimmune care. In oncology, for example, scientists have mapped out a long list of immune escape pathways that tumors use to hide from T cells, including the KIR3DL3-HHLA2 axis, the KIR2DL5/PVR pathway, GPR56, and HVEM/BTLA, with references numbered 373 and 374 among others in a detailed review of Such immune escape mechanisms. The success of checkpoint inhibitors that target these pathways has shown that carefully lifting or redirecting immune brakes can produce durable clinical benefits, a lesson that is now informing how neurologists think about microglial receptors and inflammatory cytokines in Parkinson.

Autoimmune research offers another template. In type 1 diabetes, for instance, disease-modifying therapies aim to “Reprogramming the Immune System While cell therapy replaces lost cells,” so that T cells stop mistaking the pancreas’s beta cells for intruders, as described in a detailed explainer on Disease Modifying Therapies. Similar thinking is emerging in neurology, where the goal is to stop immune cells from misidentifying neurons as threats. Basic research in other chronic conditions, such as diabetic peripheral neuropathy, has already “shown promising therapeutic targets and pathways and paved the way for novel approaches beyond a merely symptomatic treatment,” highlighting how Basic immune insights can translate into new disease-modifying strategies.

More from Morning Overview