Researchers have engineered tiny gold nanospheres that can soak up almost the entire spectrum of solar energy, promising a step change in how efficiently we turn sunlight into usable power. By packing gold nanoparticles into tightly clustered “supraballs,” the team has created a material that captures a far broader range of wavelengths than conventional solar coatings. As heat waves intensify and electricity demand spikes, that kind of broadband absorption is no longer a laboratory curiosity, it is a potential tool for keeping grids stable and emissions in check.

Instead of relying on new semiconductor chemistries, the work leans on the unusual optical behavior of gold at the nanoscale, where particles interact with light in ways bulk metal never could. The result is a film that not only drinks in visible light but also reaches deep into the infrared, where a large share of the Sun’s energy actually sits. I see this as part of a broader shift in solar research, away from chasing marginal gains in cell efficiency and toward rethinking how we harvest every photon that hits a surface.

Why sunlight still outruns today’s solar tech

Modern solar panels are far better than the clunky modules that appeared on rooftops a generation ago, yet Sunlight still carries more energy than most devices can capture. Standard silicon cells are tuned to a relatively narrow slice of the spectrum, which means a lot of incoming radiation either passes through or is lost as heat. That mismatch becomes more costly as climate change drives longer, hotter summers and pushes air conditioners, data centers, and electric vehicles to draw more power at the very hours when the Sun is strongest.

In that context, the idea of a coating that can drink in nearly the full range of wavelengths present in Sunlight is more than a scientific milestone, it is an efficiency play with direct economic stakes. The new gold nanospheres are designed to address exactly this gap, turning surfaces into broadband absorbers rather than single-band specialists. Reporting on the initial experiments describes how the nanospheres were tuned to interact with a wide span of frequencies, a strategy that could help close the long standing gap between the energy Sunlight delivers and what solar hardware actually converts to electricity, as detailed in early coverage of the nanosphere design.

Inside the gold supraballs

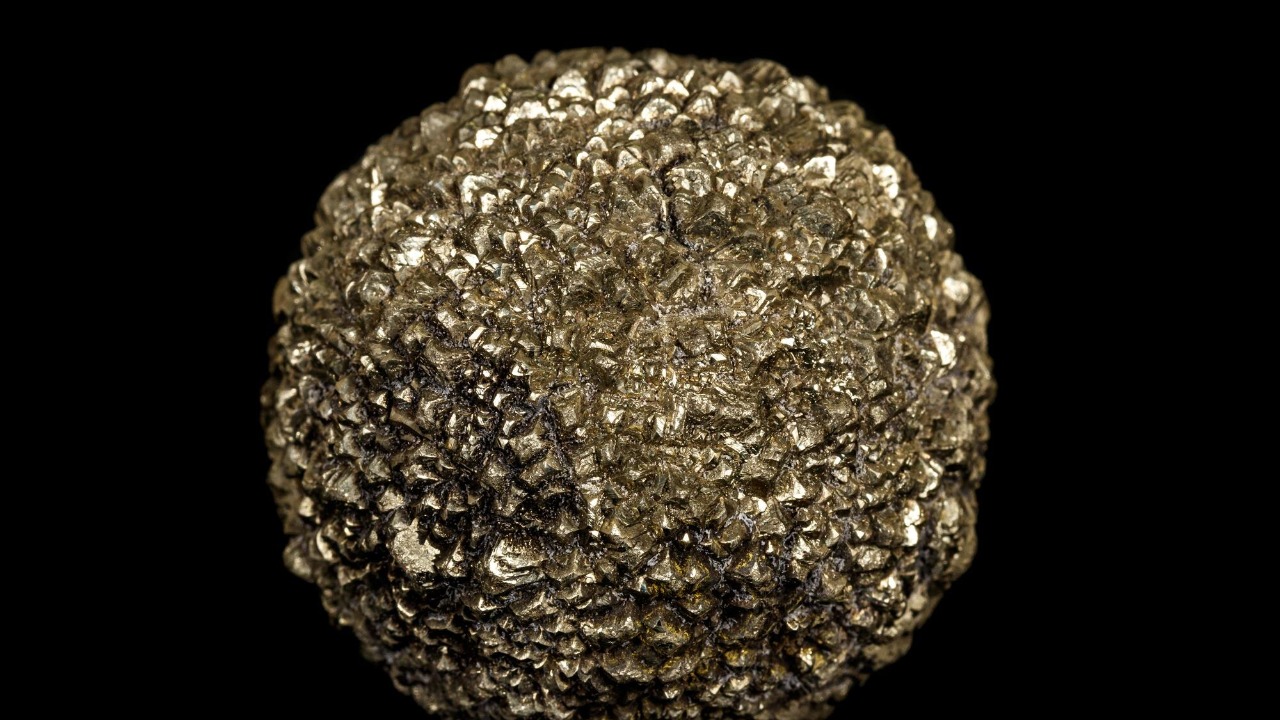

The core of the breakthrough is a deceptively simple structure, clusters of gold nanoparticles that self assemble into compact spheres. Each supraball is made from hundreds of individual particles, and by adjusting the overall diameter the researchers were able to maximize how much light the structure absorbs. Earlier this year, they reported that these gold NPs naturally clump together into tiny spheres when conditions are tuned correctly, creating a dense, three dimensional network that interacts with incoming radiation far more strongly than a flat metal film.

What makes these supraballs so effective is the way they combine nanoscale physics with macroscale practicality. At the nanoparticle level, gold supports intense localized surface plasmon resonances, which means electrons on the particle surface oscillate collectively when hit by light, boosting absorption. When hundreds of such particles are packed into a single supraball, those resonances overlap and broaden, extending the range of wavelengths that can be captured. The team behind the work describes how they optimized the diameter of these structures to maximize absorption, noting that the resulting gold supraballs are relatively easy to manufacture and inexpensive compared with more exotic nanophotonic materials, a point underscored in technical summaries of the gold NPs supraballs.

From self assembly to nearly full spectrum capture

What sets this research apart is not only the clever use of gold but also the way the particles organize themselves. Instead of painstakingly patterning each feature, the scientists relied on self assembly, letting the gold nanoparticles form supraballs as a liquid solution dried. That approach is central to the claim that these structures could scale beyond the lab, because it replaces expensive lithography with a process closer to ink formulation. The researchers describe the supraballs as self assembling units that can be deposited as a film, creating a coating that interacts strongly with Sunbeams across a wide range of colors.

The payoff from this self assembly strategy is a material that captures far more of the Sun’s output than typical solar coatings. Reports on the work emphasize that Sunbeams contain a lot of energy, but current harvesting technology does not capture as much as it could, a gap the team set out to close by using self assembling gold supraballs. By carefully controlling particle size and packing, they created a film that responds to both visible and infrared light, effectively broadening the usable spectrum. The description of how Sunbeams are harnessed more completely by these structures is laid out in the group’s explanation of their self assembling supraballs, which highlights the contrast with conventional, narrower band absorbers.

Simulations, coatings, and real world performance

To move beyond elegant theory, the team leaned heavily on simulation to understand how individual supraballs and entire films would behave under real sunlight. Computer models allowed them to test different particle sizes, packing densities, and layer thicknesses before committing to fabrication, a crucial step when dealing with complex optical interactions. According to technical accounts of the work, they used these simulations to determine the efficiency of the supraballs and to refine the design of individual particles and assemblies, work that was ultimately reported in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces and summarized in coverage of the project’s simulation methods.

Once the models pointed to a promising configuration, the researchers turned to physical coatings. They deposited a film of the gold supraballs onto a substrate and measured how much solar energy it absorbed over time. In one test, they evaluated a coating on a surface exposed to natural sunlight from 11:00 to 13:00 KST, a window that captures the most intense midday radiation. During that period, the nanosphere film averaged about 45.20 percent absorption, a figure that reflects both the broadband nature of the material and the practical realities of outdoor conditions. The details of that experiment, including the specific time window and the 45.20 percent performance, are described in reports on the coating test, which frame it as an early but encouraging sign that the lab results can translate into real world gains.

What gold supraballs could mean for future solar systems

If these nanospheres can be produced at scale, they could reshape how engineers think about solar hardware. Instead of focusing solely on the semiconductor inside a panel, designers could add a supraball layer that captures a broader spectrum and funnels that energy into electricity or heat. One scenario is to use the coating on the front of photovoltaic modules to pre absorb high energy photons and reduce reflection, while another is to apply it to thermal collectors that turn sunlight into hot fluids for industrial processes. The fact that a supraball is made from hundreds of gold nanoparticles yet is still described as relatively easy to manufacture and inexpensive compared with many nanostructured materials suggests that cost may not be the barrier it once was for plasmonic technologies, a point highlighted in descriptions of how each supraball is assembled.

More from Morning Overview