Hydrogen has long been sold as a clean fuel, yet most of it is still produced from fossil gas with a heavy carbon footprint. A new electrochemical route now promises to flip that script by turning waste glycerol from biodiesel production into hydrogen and formate without generating additional CO₂. By pairing a tailored catalyst with a modified electrolysis setup, researchers say they can produce both energy and a valuable chemical feedstock while cleaning up a stubborn industrial byproduct.

The work, led by a team at JGU, replaces the conventional oxygen-forming half of water electrolysis with a reaction that upgrades glycerol into formate. In doing so, it cuts the energy demand of hydrogen production and avoids the CO₂ emissions that usually accompany reforming of hydrocarbons. If powered with renewable electricity, the process offers a route to what the team describes as CO₂‑neutral hydrogen and formate from a waste stream that the biodiesel industry struggles to use efficiently.

From biodiesel byproduct to electrochemical feedstock

Glycerol is generated in large quantities as a byproduct when biodiesel is manufactured, and much of it is too impure to sell into higher value markets. Instead of treating this stream as a disposal problem, the JGU group treats crude glycerol as a starting material for electrolysis, effectively turning waste into a reagent. In their work, the researchers explicitly frame the process as a way to convert glycerol into formate and hydrogen in a CO₂‑neutral manner, provided the cell is powered with sustainable electricity, a claim they link to a broader push for climate‑friendly hydrogen production at JGU.

Instead of splitting pure water into hydrogen and oxygen, the system feeds glycerol into the anodic side of the cell, where it is oxidized to formate. That change in chemistry matters because oxidizing glycerol requires less energy than generating oxygen, which lowers the overall voltage needed to drive the cell. The team describes the approach as an adaptation of established water electrolysis, but with the anodic reaction swapped out for glycerol upgrading, a configuration that is detailed in their description of the new process.

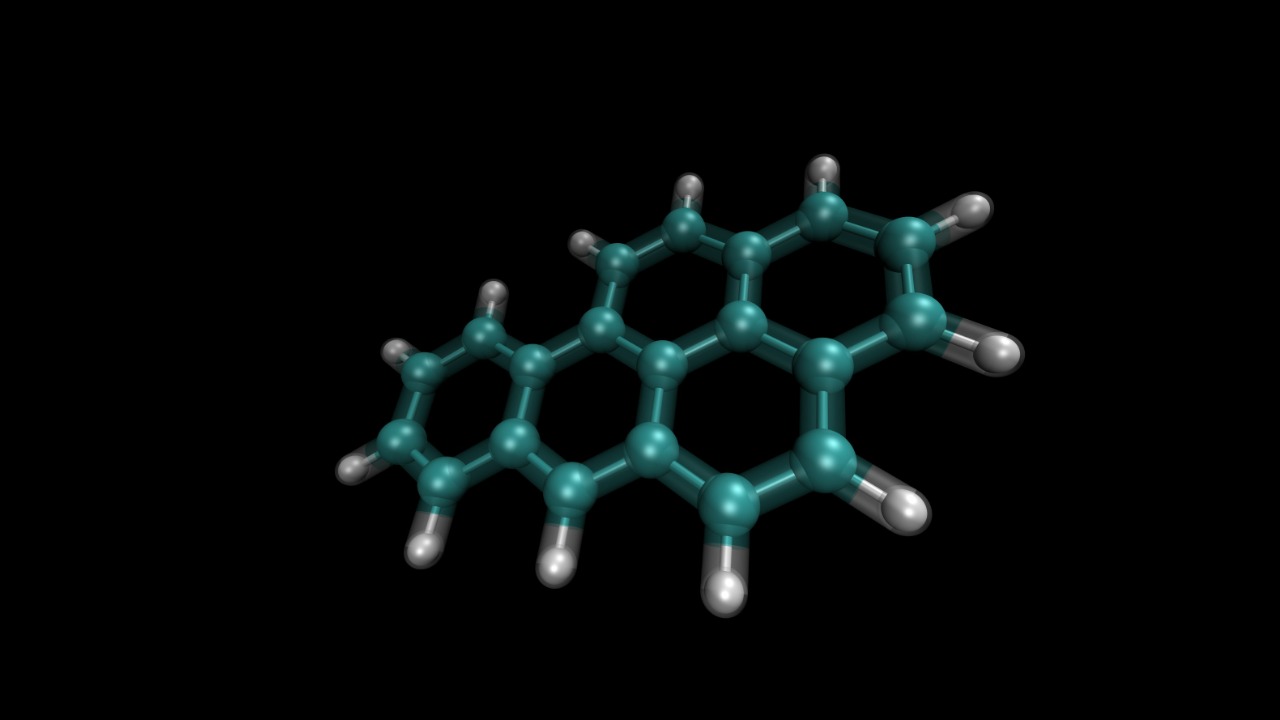

A tailored catalyst at the heart of the cell

The core of the advance is a catalyst engineered specifically to steer glycerol toward formate rather than a messy mix of partial oxidation products. On the molecular level, the catalyst surface is tuned so that glycerol is broken down in a controlled sequence of steps, stopping at formate, which contains just a single carbon atom and can be handled as a stable anion in solution. The researchers emphasize that this selectivity is not accidental but the result of designing an innovative catalyst that can manage both the oxidation of glycerol and, in a second stage, a reductive electrolysis process, a dual role highlighted in their description of the new catalyst.

On the cathodic side, the cell still performs the familiar hydrogen evolution reaction, but it does so at a lower applied potential because the anodic step is now easier. This pairing of a glycerol‑to‑formate oxidation with hydrogen evolution allows the device to generate two useful products in a single integrated setup. The team describes the overall configuration as a CO₂‑neutral production route for formate, rooted in the same basic physics as water electrolysis but re‑engineered so that the carbon in glycerol is conserved as formate rather than released as CO₂, a point they underline in their explanation of CO₂‑neutral production.

Why formate matters in a hydrogen economy

Formate might sound like a niche chemical, but it plays several roles that make it attractive in a low‑carbon energy system. It can serve as a liquid carrier for hydrogen, a buffering agent, and a feedstock for various chemical syntheses, which means a process that generates formate alongside hydrogen can tap into multiple value chains. The JGU team explicitly frames formate as a product with its own market potential, not just a side stream, and notes that capturing the carbon from glycerol in this way avoids the climate penalty that would come from simply burning or discarding the byproduct, a framing that appears in their broader discussion of climate‑friendly generation.

In practical terms, producing formate electrochemically from glycerol could give biodiesel plants a new revenue line while also supplying chemical manufacturers with a lower‑carbon input. Because the process is designed to be CO₂‑neutral when powered by renewable electricity, the resulting formate and hydrogen could qualify as low‑emission inputs under emerging regulatory schemes that differentiate products by their lifecycle emissions. That linkage between sustainable electricity, hydrogen output, and formate production is central to the description of how electrolysis converts glycerol into marketable products.

Energy savings and emissions impact

Replacing the oxygen evolution reaction with glycerol oxidation does more than add a second product stream, it also cuts the energy bill for hydrogen production. The oxidation of glycerol to formate is thermodynamically easier than splitting water to oxygen, so the cell can operate at a lower voltage for the same hydrogen output. That reduction in required potential translates directly into lower electricity consumption per kilogram of hydrogen, a critical metric for green hydrogen projects that must compete with fossil‑based hydrogen on cost, and it is a benefit the researchers highlight when they describe the new route as an electrolysis method that can be operated with sustainable power at JGU, a point captured in their account of how JGU develops an.

From an emissions perspective, the process sidesteps the CO₂ that would be released if glycerol were combusted or reformed thermally, and it avoids the fossil carbon associated with conventional hydrogen production from natural gas. The researchers explicitly describe the combined hydrogen and formate output as CO₂‑neutral when the cell is powered with renewable electricity, since the carbon in glycerol is retained in formate rather than oxidized to CO₂. That framing aligns with their broader characterization of the work as a climate‑friendly generation pathway that builds on established water electrolysis while reconfiguring the anodic chemistry, a description they provide when outlining how new process is on familiar electrochemical principles.

Scaling challenges and international collaboration

As promising as the lab‑scale results are, moving this technology into industrial practice will require careful work on durability, impurity tolerance, and integration with existing biodiesel infrastructure. Crude glycerol can contain salts, methanol, and other contaminants that may poison catalysts or foul membranes, so the electrolysis system will need to handle real‑world feedstocks without excessive pretreatment. The researchers acknowledge that the project is international in scope and benefits from the ability to recruit talent across borders, a point they make when describing how the effort, led by Jan and colleagues, draws on a diverse team to refine the climate‑friendly generation concept into a robust technology.

Policy and market signals will also shape how quickly such a process can scale. If hydrogen buyers and chemical producers begin to pay a premium for CO₂‑neutral inputs, biodiesel plants could find it attractive to bolt on electrolysis units that convert their glycerol into hydrogen and formate. The fact that the work is anchored at JGU, with researchers explicitly focused on a Neutral Electrolysis Method to Produce Formate and Hydrogen from Glycerol, suggests a deliberate attempt to align academic innovation with industrial needs, a positioning that is evident in the description of how Researchers Develop a route that can plug into existing renewable electricity systems.

More from Morning Overview